"With his divine alchemy, he [God] turns not only water into wine, but common things into radiant mysteries, yea, every meal into a Eucharist, and the jaws of death into an outgoing gate."

While he reserved a place in his theology for hell (though not an eternal one), George MacDonald was more fascinated with God's triumphant love: "I believe that no man is ever condemned for any sin except one—that he will not leave his sins and come out of them, and be the child of him who is his Father."

Timeline |

|

|

1806 |

Samuel Mills leads Haystack Prayer Meeting |

|

1810 |

American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions |

|

1819 |

Channing issues Unitarian Christianity |

|

1824 |

George MacDonald born |

|

1905 |

George MacDonald dies |

|

1914 |

World War I begins |

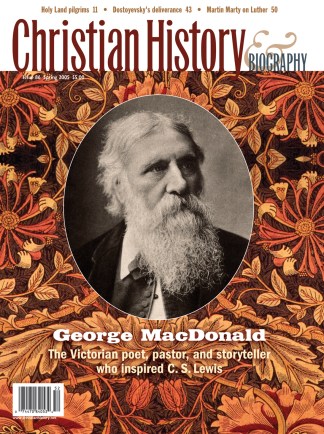

This poet, preacher, and writer of fairy tales was taken with the quote, "Our life is no dream; but it ought to become one, and perhaps will." His vision of the mystery that surrounds us and the fantastic world awaiting us enthralled readers in both Victorian England and post-Civil War America.

Transatlantic fame

After being raised in Huntley, Aberdeenshire, by devout Calvinist parents, he attended King's College in Aberdeen. At Highbury Theological College, he received his divinity degree, and in 1850 he became a pastor of a Congregational church in Arundel. Early the following year, he married Louisa Powell, with whom he enjoyed a long and happy marriage.

The Scotsman was forced to resign his pulpit in 1853 because he liked to dabble in "German theology," meaning the new higher critical approach to biblical studies emerging from that country. He never took another church but spent the rest of his life lecturing, preaching, and especially writing.

Between 1851 and 1897, he wrote over 50 books in all manner of genre: novels, plays, essays, sermons, poems, and fairy tales. And then there were his two fantasies for adults, Phantastes (1858) and Lilith (1895), which defy categorization. During these years, Lewis Carroll became a good friend and gave him the first manuscript of Alice in Wonderland to read to his children. Other British literary luminaries—like John Ruskin, Charles Kingsley, Lord Tennyson, and Matthew Arnold—were among his associates and admirers.

When McDonald visited the United States in 1872 for a lecture tour, the likes of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Greenleaf Whittier, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Mark Twain paid him homage. After his stay in New York City, one large Fifth Avenue church offered him the almost unheard of salary of $20,000 a year to become its pastor. MacDonald thought the idea preposterous.

His success did not exempt him from more-than-ordinary suffering. Poverty plagued him so much that his family occasionally faced literal starvation. His own lungs were diseased, and tuberculosis killed two brothers and two half-sisters. It also ravaged his children, four of whom died before him. He himself had a stroke at age 74 and lapsed into virtual silence for the last seven years of his life.

Still, MacDonald believed suffering was finally redemptive: "All pains, indeed, and all sorrows, all demons, yea, and all sins themselves, under the suffering care of the highest minister, are but the ministers of truth and righteousness."

Inspiring writers

MacDonald eventually became an Anglican, but he never had much patience with high theology or liturgy—he said it often stood in the way of people encountering Christ personally. Furthermore, it wasn't just the church but all of creation that revealed God: "With his divine alchemy, he [God] turns not only water into wine, but common things into radiant mysteries, yea, every meal into a Eucharist, and the jaws of death into an outgoing gate."

MacDonald's popularity has faded with time, though he retains a small, loyal following, and his The Princess and the Goblin (1872) and The Princess and Curdie (1883) are still read by children. But in his day, he inspired not a few of the 20th century's favorite writers, like G.K. Chesterton, J.R.R. Tolkien, Madeleine L'Engle, and C.S. Lewis, to name four. "I have never concealed the fact that I regarded him as my master," wrote Lewis; "indeed I fancy I have never written a book in which I did not quote from him."

Corresponding Issue