Maniac or Martyr?

By Elesha Coffman, assistant editor of CHRISTIAN HISTORY

Mrs. Jefferson Davis called him "a pestilent, forceful man" motivated by "insane prejudice." Louisa May Alcott, the author of Little Women, referred to him in her diary as "Saint John the Just." A Richmond, Virginia, newspaper announced, "The miserable old traitor and murderer belongs to the gallows," while in Concord, Massachusetts, Henry David Thoreau pleaded "not for his life, but for his character." John Brown was a man you either loved or hated, feared or followed.

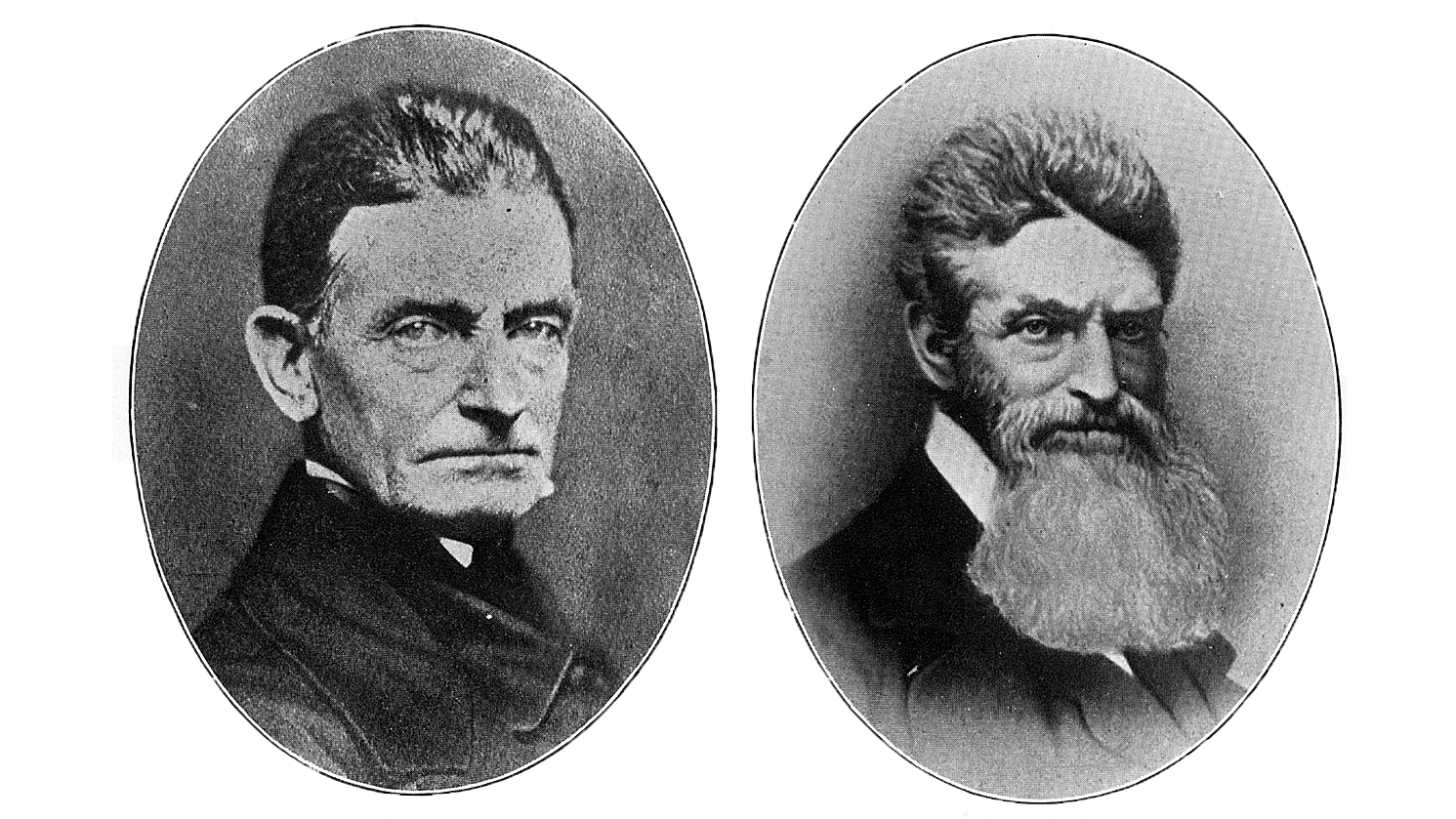

Born 200 years ago this week (May 8), Brown was an unstable man in unstable times. Mental illness plagued his mother and a few of his 20 children, and one look into his eyes (there's a good picture at the PBS Web site listed below) arouses strong suspicion that all was not right in his mind, either. Every attempt he made to support his family—including tanning, land speculating, and sheep herding—failed due to economic crashes or his own bad decisions. Often driven by financial need, he moved back and forth through the center of a nation increasingly split between north and south. Wherever he went, if fires weren't already burning, he had a tendency to light them himself.

Through most of his adult life, Brown was concerned first and foremost for his family's survival, but he was also motivated by vigorous abolitionist beliefs. His barn in Pennsylvania was a stop on the Underground Railroad, and he once declared during an Ohio church service, "Here, before God and in the presence of these witnesses, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery." Even so, it was only during the last four years of his life that he felt God calling him to battle and directed all his energies toward abolition.

Brown's first actual battle occurred in Kansas in 1855. The territory was in turmoil as settlers rushed in from north and south; whichever faction could take hold of the territorial government could decide whether Kansas would be slave or free. Two of Brown's sons had moved there to held tip the scales toward freedom, but pro-slavery forces (including the "border ruffians" streaming in from Missouri) had the upper hand. Brown responded to his sons' call for backup—especially guns—and organized an anti-slavery militia "to cause restraining fear," as he put it.

Following the publicized murders of several abolitionists, Brown's men hacked to death five pro-slavery settlers in Pottawatomie, including Mahala Doyle's husband and two of her sons. Years later, she wrote to him in prison, "Altho' vengeance is not mine, I confess that I do feel gratified to hear that you were stopped in your fiendish career. … My son John Doyle whose life I beged [sic] of you is now grown up and is very desirous to be at Charlestown on the day of your execution."

But Brown was not executed for the Pottawatomie killings; he escaped into the woods. The campaign that proved fatal was his plan, based on visions he'd had years earlier, to seize a stronghold in the mountains of Maryland or Virginia, where he would gather slaves and arm them. He hoped to touch off a slave uprising through which slavery would ultimately collapse. The stronghold he chose was the armory at Harper's Ferry, Virginia.

Brown gathered a band of 21 men and led them across the Potomac River on October 16, 1859. They quickly seized the armory and convinced or compelled a few slaves to join them (a free black was also, unfortunately, killed in the confusion). Within a day, a company of U.S. marines commanded by Col. Robert E. Lee assaulted the building, and though Brown fought courageously (at one point over the body of his dying son), Lee's forces prevailed. Brown was captured, sentenced to death, and hanged on December 2, maintaining to the end the rightness of his actions.

"I believe that to have interfered as I have done, as I have always freely admitted I have done in behalf of His [God's] despised poor, I did no wrong, but right," he told the court that convicted him. "Now if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel and unjust enactments, I say, let it be done."

Earlier this year, PBS aired the impressive documentary "John Brown's Holy War," which I watched but didn't know about in time to recommend. Instead, I'll highly recommend the Web site for the documentary, www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/brown/. With the full film transcript, transcripts of contributing interviews, primary source material, a timeline, maps, and a teacher's guide, the site is a treasure trove of information. Brown also appears in Christian History issue 33: Christianity and the Civil War.

Incidentally, there is no connection between this John Brown and John Brown University in Siloam Springs, Arkansas. The school is named for a lay minister in the Salvation Army who advocated education for those who couldn't afford it—a much more logical choice.

Elesha Coffman can be reached at cheditor@ChristianityToday.com.

Copyright © 2000 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.