Another day, another high-profile sex scandal. Many Americans yawned when Arnold Schwarzenegger’s extramarital activities hit the headlines two weeks ago. By now it’s difficult to escape the fatalistic feeling that we’ve seen it all before and will see it all again, and soon.

Another day, another high-profile sex scandal. Many Americans yawned when Arnold Schwarzenegger’s extramarital activities hit the headlines two weeks ago. By now it’s difficult to escape the fatalistic feeling that we’ve seen it all before and will see it all again, and soon.

To their credit, though, some Christians took the opportunity to discuss practical ways of staying faithful to one’s spouse. On his website, Michael Hyatt, chairman and CEO of Thomas Nelson Publishers, wrote a post titled, “What Are You Doing to Protect Your Marriage?” Hyatt listed tips such as investing time and energy in one’s marriage, remembering what’s at stake, and setting specific boundaries. The boundaries Hyatt sets for himself, which he says “may sound old-fashioned, perhaps even legalistic,” are the following:

I will not go out to eat alone with someone of the opposite sex.

I will not travel alone with someone of the opposite sex.

I will not flirt with someone of the opposite sex.

I will speak often and lovingly of my wife. (This isthe best adultery repellant known to man.)

I really appreciate that Hyatt and other Christian leaders are addressing this issue, because I know what it’s like to watch a Christian leader fall. When I was 15, the senior pastor at my church—a man deeply beloved and admired by his congregation—left his wife for his secretary. Words can’t capture the spiritual and emotional devastation this man and woman left in their wake. Though they would eventually repent and confess their sin before the church, some of us carry scars to this day. So I can be nothing but grateful for Christians who make the effort to stay pure and who teach others to do the same.

At the same time, I want to humbly offer a word of caution: Sometimes, practical tips like the ones I’ve described can lead to practical problems.

Jon Acuff of Stuff Christians Like fame discovered this when he wrote a post on “Awkward opposite sex friendships,” inspired by his decision to request a male driver when he spoke at a conference. In the post, Acuff acknowledged some of the difficulties that can come up when Christian men work or have other public interactions with women:

What about having a one on one meeting with a woman? Is it enough to just leave the door open? Or do you have to have three people present at all times? I know churches who use both approaches.

What about a lunch meeting? A married friend recently told me that if he couldn’t go out to lunch with females he couldn’t do his job. Is lunch with a lady a date? What if it’s a business lunch? The CEO of Zondervan is a lady, what if she calls me and says, “Jon, we’d like to give you a 37 book deal and your own Honda Ruckus Scooter for a cross country tour called ‘Ruckus by Ruckus,’ can we go out to lunch to discuss the details?” Do I have to invite someone along with me? What if my wife is not available that day?

Acuff knew that he was broaching an “awkward” subject, and admitted he didn’t have any hard and fast solutions, but I doubt he was prepared for the way his comment section exploded on the post. While some of his commenters agreed that his boundaries were justified, many others wrote to tell him just how many difficulties such boundaries can cause for working women.

The dissenters’ consensus seemed to be not that there shouldn’t be boundaries, but that those boundaries should be drawn in a way that respects women as working professionals trying to do their jobs. Several of them asked Acuff to stop and think about what it’s like to be a woman who’s told that a man doesn’t want her driving him solely because of her gender. Turning down even a one-time ride can give a woman the unpleasant impression that she’s viewed not as a professional person but as a sexual temptation waiting to happen.

Admittedly, it’s a much harder task to create boundaries when you try to factor these things in. But when we don’t, we run the risk of going to un-Christlike extremes. Christian women working for churches and other ministries have been left out of important discussions and meetings because of unrealistic boundaries. A commenter on Acuff’s site confessed that years ago, he and several other seminary students working at a restaurant had refused to give a ride home to an older woman with car trouble, because, well, she was a woman.

One prominent pastor used to say that if he were driving alone in his car on a rainy day and passed a woman from his church walking down a road, he wouldn’t stop to pick her up. Now, maybe I’m being naïve, but would someone tell me exactly how much two people can accomplish in a car while one of them is driving it?

On a more serious note, this anecdote makes me wonder if this man had ever preached on, or even read, the Parable of the Good Samaritan. Or did he feel okay about it because the beaten-up man in the story wasn’t a beaten-up woman?

Of course, as I stressed earlier, boundaries are crucial in preserving marriages. But overdoing those boundaries can reduce interactions between Christian men and women to something that looks like the “wicked city woman” skit on I Love Lucy. To avoid this problem and to create boundaries that really work, I believe we need to learn to see each other—and ourselves—in a more holistic way. What I mean is, instead of viewing the women in their world as potential problems to be avoided as much as possible, and viewing themselves as explosives wired to go off if the heat gets too high, Christian men might want to try something different. They might practice viewing everyone concerned as human beings who are made in God’s image, and are therefore to be treated with respect, courtesy, and an approach that’s neither too familiar nor too distant.

As we discussed Hyatt’s post, Her.meneutics writer Ellen Painter Dollar came up with an analogy I really like:

I think of a parallel to weight loss advice. No one says to people trying to lose weight or maintain weight loss, “Never go to a wedding or holiday party again. Never walk into a bakery again.” Instead, they offer strategies for how to minimize temptation in situations where temptation will be greater. Seems like that’s a more realistic approach to this topic.

Because women aren’t about to vanish from either the church or the workplace, it may be that men are better off learning to deal with our presence than trying to minimize it. There’s plenty of room for debate about what such an approach might look like. But to base our boundaries on this idea might just be healthier, not only for men’s and women’s careers, but for their marriages and spiritual lives as well.

Gina Dalfonzo is editor of BreakPoint.org and Dickensblog. She wrote “The Good Christian Girl: A Fable” and “God Loves a Good Romance” for CT online, and “Bill Maher Slurs Sarah Palin, NOW Responds,” “The Social Network’s Women Problem,” “Facebook Envy on Valentine’s Day,” “What Are Wedding Vows For, Anyway?” “Why Sex Ruins TV Romances,” and “Don’t Think Pink” for Her.meneutics. Her book, “‘Bring Her Down’: How the American Media Tried to Destroy Sarah Palin,” is now available on Amazon.Sarah Hinlicky Wilson and Lauren Winner debated the topic of male-female workplace boundaries for Christianity Today in 1999.

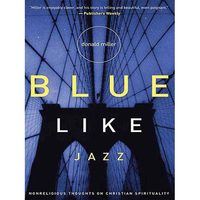

Looks like the Blue Like Jazz film project, delayed several times, finally has a green light.

Donald Miller, author of the book on which the movie is based, blogged recently that director Steve Taylor (The Second Chance) is moving forward on shooting Blue Like Jazz the movie. He’s set to shoot in Mid May through June. We will be shooting in Portland and Nashville through the end of June. I couldn’t be more excited.”

Miller and Taylor had hoped to get the movie rolling last year, but had to put the project on hold due to a lack of funding.

They’ve apparently got enough money to move forward now, though they’re still seeking “associate producers” (at $99.95 a pop) to help defray costs.

Last spring The Intelligent Life, a journal published by The Economist, ran an article claiming that Americans are overall an “unhappy lot.” Two years ago, The New York Times published “Liberated and Unhappy,” about the diminishing degree of happiness among American women (Her.meneutics weighed in too). And recently I stumbled across the website for The Happiness Project, a book by Gretchen Rubin that shot to number two on the NYT bestseller list within its first week of publication last year. I am still dizzy from the swirl of quotes and tips on the website about how to pursue happiness and join in on booming nationwide happiness-projects. The amount of literature being penned on happiness suggests that as a culture we want to believe that happiness is something we can will and achieve, and that it is our inalienable right and our due. At times, I too am guilty as charged.

Last spring The Intelligent Life, a journal published by The Economist, ran an article claiming that Americans are overall an “unhappy lot.” Two years ago, The New York Times published “Liberated and Unhappy,” about the diminishing degree of happiness among American women (Her.meneutics weighed in too). And recently I stumbled across the website for The Happiness Project, a book by Gretchen Rubin that shot to number two on the NYT bestseller list within its first week of publication last year. I am still dizzy from the swirl of quotes and tips on the website about how to pursue happiness and join in on booming nationwide happiness-projects. The amount of literature being penned on happiness suggests that as a culture we want to believe that happiness is something we can will and achieve, and that it is our inalienable right and our due. At times, I too am guilty as charged.

I cannot help reflecting on our cultural obsession with happiness against the backdrop of Easter, these 50 days of invitation to dwell in the reality of resurrection. If the church could claim to have an official “happy season,” this would be it. Christ is risen. New life is possible in all circumstances. But, instead of the temptation to appropriate a Christian interpretation of a cultural phenomenon, perhaps the real place to begin is to consider that happiness may not be a word in our Christian vocabulary.

That’s not to say Christians cannot experience happiness. Rather, we recognize happiness as transitory as opposed to a telos after which we earnestly seek. Reflecting on Scripture and the call to discipleship, the closest Christians might get to notions of happiness is by practicing the spiritual discipline of hope, something that looks remarkably different from Western definitions or constructs of happiness.It’s a disciplineto whichChristcalls us as surely as we are called to service, prayer, fasting, and other disciplines. What we ultimately hope for is the full healing of creation, because we recognize that life is not fully as it should be. Ironically, it is this universal recognition that propels the secular hamster wheel spinning toward illusions of finding happiness.

Choosing the discipline of hope over the pursuit of happiness starts with acknowledging that just like the Christian liturgy, our habits shape us. Each time we practice being hopeful, we open ourselves to being formed into creatures who might recognize glimpses of resurrection life this side of the kingdom. Despite the broken circumstances of our individual and collective lives, we remain foolishly open to expecting bread instead of stones, and to the certainty that there always exists another reality to the one in which we find ourselves.

As Christians we face the decision each day of which narrative we will live into for one more day: the one where Christ is Lord, or one of the gazillion others up for grabs. It is an ongoing discipline to choose the former, to choose hope especially when the odds seem to be against a hopeful future.

Like happiness, hope can be hard to maintain. But unlike happiness, it is not a chase down a rabbit trail of new purchases, rehashed advice, and mantras. Rather, hope cultivates a distinct posture toward the world that is grown and sustained through conscious daily practices enacted within our varied circumstances, the good and the bad. It is a discipline we engage in daily whether we feel like it or not, whether we see any immediate results or not. It witnesses to another sovereignty besides ourselves, and another claim that what we see or experience in this fractured world, delightful or deeply painful, is not the lasting reality.

Hope has holy and human relationship at its center. When Christ appeared after his resurrection, the first thing he did was create the church. God knows that choosing and claiming divine reality and holy imagination is not something we do easily or quickly. Rather, we assist one another to practice the spiritual disciplines that foster abundant, hopeful life. Practicing hope is a way of learning to be fellow burden bearers and memory-keepers for one another when the realities of our lives threaten injustice, fear, pain and darkness, or simply threaten to suggest God is not able.

Hope acknowledges that the sundry list of life’s difficulties are never what God intends for a healed kingdom, and that God never leaves us bereft. At one stage of my own life, while in a committed relationship to a recovering alcoholic, practicing hope meant waking up each day and choosing to resist the constant temptation to query my boyfriend about how he was “doing” and whether or not he would attend an AA meeting that day, but still recognizing the importance of rejoicing in marked points of sobriety. Hope believes that all circumstances are redeemable at the foot of the cross and yet celebrates our difficult human efforts to live into that redemption. For my girlfriend exhausted with the disappointment of infertility, hope resembles accepting the invitation of friends who desire to take on the burden of prayer for this particular struggle. Hope recognizes that we do not walk alone and sometimes we carry others for part of the journey.

Hope does not anticipate or rely on a happy ending. Hope believes that the God who came to give us abundant life is always at work.

Enuma Okoro was born in the United States and raised in Nigeria, Ivory Coast, and England. She holds a Master of Divinity from Duke Divinity School where she served as director for the Center for Theological Writing. The author of Reluctant Pilgrim and co-author of Common Prayer (with Shane Claiborne and Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove), Enuma lives in Raleigh, North Carolina. She blogs at EnumaOkoro.com.

Back to Miller’s blog entry: “I’m skyping today with the actor who will likely play me. Unfortunately I can’t tell you who it is until we sign contracts, but we are both stoked on the choice.” Miller and Taylor joke on the “from the director” video that Brad Pitt was the No. 1 choice.

Or was it a joke? If Pitt can age backwards in a movie, certainly he’s got the acting chops to play a curious case like Mr. Miller. 😉