"The shooting of abortion physician George Tiller continued a long, dark tradition in American politics," Jon Shields wrote in a fascinating op-ed for Christianity Today earlier this month. "Radicalism on the fringes of social movements has been a surprisingly enduring phenomenon in American politics. There were violent abolitionists, axe-wielding temperance crusaders, Black Panthers in the civil rights movement, Weathermen in the New Left, and eco-terrorists in the environmental movement."

Indeed, in the wake of Tiller's murder I've seen more discussion of Christian history than I've seen since The Da Vinci Code movie came out. Shields points to various social movements, but in the blogosphere over the past few weeks there has been a focus on two particular moments in history: Dietrich Bonhoeffer's participation in an attempted assassination of Adolf Hitler, and the violent abolitionism of John Brown, Nat Turner, and others.

"When it came to defying Hitler's regime, Bonhoeffer saw that several excruciating moral questions were on ‘the borderland’ and could not be settled with absolute certainty," Al Mohler wrote in an op-ed for the Chicago Tribune. "Eventually, he was convinced that the Nazi regime was beyond moral correction and no longer legitimate. Christians, he then saw, bore a responsibility to oppose the regime at every level and to seek its demise. He acted in defense of life and was finally willing to use violence to that end."

He immediately added this: "America is not Nazi Germany. George Tiller, though bearing the blood of thousands of unborn children on his hands, was not Adolf Hitler. The murderer of Dr. George Tiller is no Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Dr. Tiller's murderer did not serve the cause of life; he assaulted that cause at its moral core. There is no justification for this murder, and it is the responsibility of everyone who cherishes life and honors human dignity to declare this without equivocation or hesitation."

Later, on his blog, Mohler seemed uncomfortable even discussing Bonhoeffer in light of the Tiller killing. "I deal with the Bonhoeffer issue in this essay because I have received so many questions about the historical analogy.," he said.

So many readers are familiar with Dietrich Bonhoeffer's decision to take action against Hitler. Fewer are familiar with the moral and theological reasoning that led Bonhoeffer, quite reluctantly, to this conclusion. Even then, Bonhoeffer was not certain he was acting rightly. He felt that this decision, made under extreme moral conditions, was the best he could understand. … We must realize that Bonhoeffer did not come to his decision to resort to violence against the regime out of a moral vacuum. He and his brothers and sisters in the Confessing Church had long before come to the conclusion that they must oppose the Nazi regime in totality, risking imprisonment and far worse. It is nothing less than embarrassing to see American Christians make arguments citing Bonhoeffer while they fail to engage his moral and theological reasoning – and when arguments are based in sloppy analogies from a position of cultural comfort.

Elizabeth Scalia made a similar point in First Things:

Bonhoeffer understood that his uniqueness in no way excepted him from the fact that what he was attempting was an evil – his evil, wholly distinct from Hitler's own evil – and one for which he would be held to account," she wrote. "Bonhoeffer knew that he could not rationalize his evil or make it less evil in the sight of Hitler's monstrous regime, and that in the end he would have only God's grace in which to hope. In another mind, another heart, particularly one beset by decades of politicized, often overheated rhetoric, who knows if such balance and genuine accountability would be possible? … When we start thinking that we know the heart and mind of God so well that we may decide who lives and who dies, we slip into a mode of Antichrist.

But if not Bonhoeffer, then what about the violent abolitionists? Randall Terry compared Tiller's killer to Nat Turner, who launched the bloodiest slave rebellion in history. Terry did not laud Turner, but compared himself to white abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison.

Garrison "did not support Nat Turner's bloody carnage, but he fearlessly declared that slavery was an intrinsic evil that was the cauldron from which Nat Turner's insurrection boiled over," Terry wrote at Catholic Online. "Garrison warned that slavery itself was the evil root from which this horrifying deed sprang. … After Nat Turner's rebellion – William Lloyd Garrison and other abolitionists actually grew more strident, more shrill, and more cutting in their rhetoric…. Remember: The powerful in the press and in politics of Garrison's day insisted that he was a ‘disturber of the peace,' and an ‘outlaw.' We now hold him as a hero."

At First Things,Wesley J. Smith also praised Garrison as someone to emulate, especially in light of the Tiller killing. "Garrison's genius was his eloquent and unyielding condemnation of that great evil," Smith wrote. "But he was also unequivocal in eschewing violence in the cause of overcoming this profound injustice."

He quoted the constitution of Garrison's American Anti-Slavery Society: "This Society will never, in any way, countenance the oppressed in vindicating their rights by resorting to physical force."

Elsewhere, Garrison more succinctly condemned abolitionist violence thus: "A good end does not justify a wicked means."

But Garrison doesn't make a great Christian hero. He saw every Christian church and denomination as utterly compromised by slavery, and black abolitionists like Frederick Douglass split with him in part because of his view of the church.

When I was writing an article on the black abolitionists for Christian History a decade ago, I was struck by how many of them saw justification for violence in both the Declaration of Independence and in Scripture. Even Douglass, who had long opposed violence, ended up supporting slave rebellions.

"The only way to make the fugitive slave law dead letter," he said, "is to make a half a dozen or more dead kidnappers."

"Kill or be killed," wrote David Walker in his famous (or infamous) 1829 Appeal … to the Colored Citizens of the World. "It is no more harm for you to kill a man who is trying to kill you than it is for you to take a drink of water when thirsty; in fact the man who will stand still and let another man murder him is worse than an infidel."

It wasn't all talk. Remember Denmark Vesey, a freed slave in South Carolina, who planned a bloody siege of Charleston after the church he founded was seized and closed.

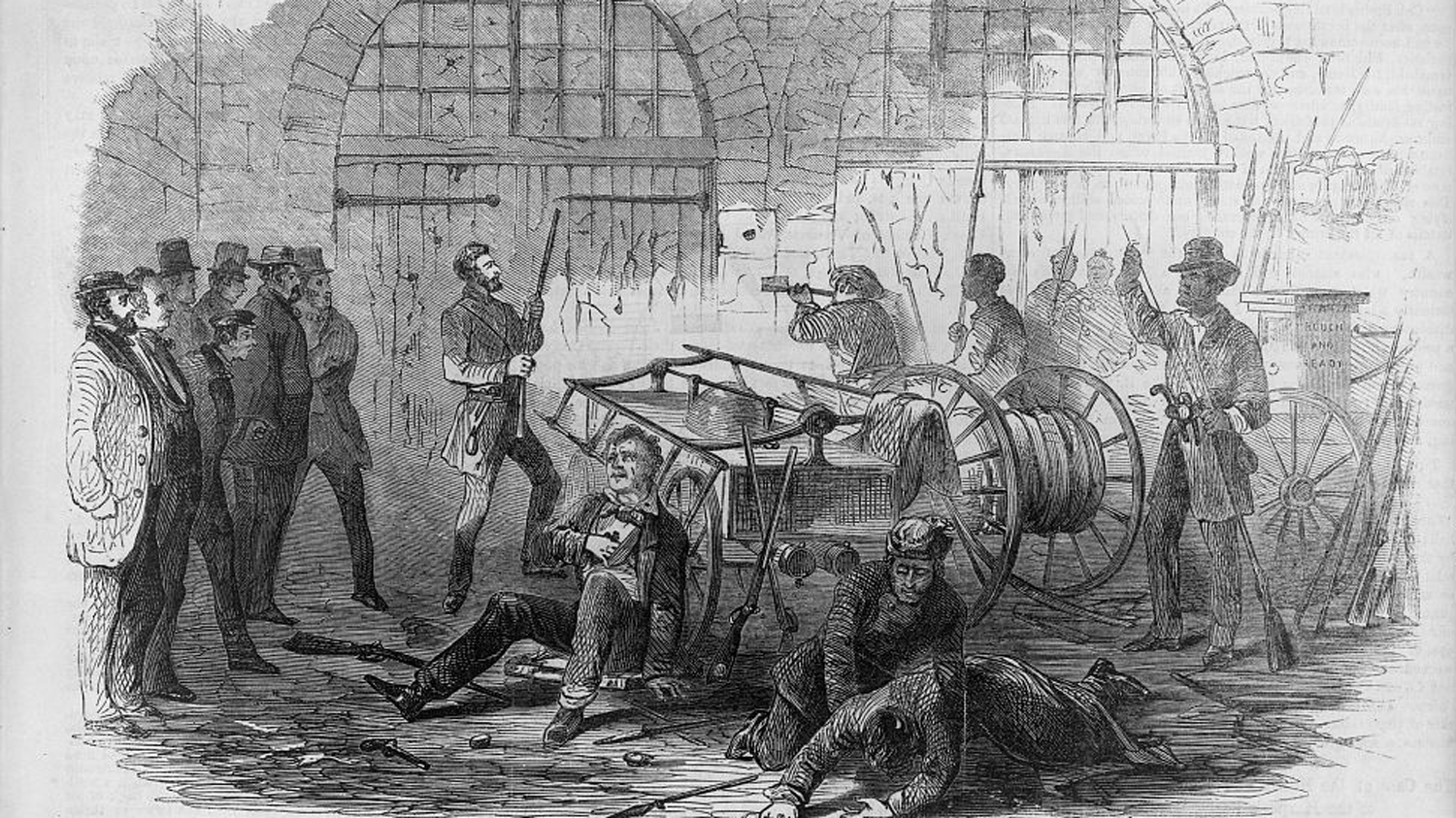

Ta-Nehisi Coates, a blogger for The Atlantic, says one reason analogies between violent anti-abortionists and violent abolitionists fail is that "political violence in 19th Century America was much more common than it is today. … Congressmen were coming to the House floor armed for a shoot-out. Why? Because of a book that slandered the South. A book. fool! … It's hard to imagine, say, Lindsey Graham beating the hell out of Patrick Leahy with a cane – and then his constituents not only keeping him in office, but sending him canes engraved with things like "Hit him again!"

Coates doesn't want to say society as a whole was more violent, but says political violence specifically seems endemic in that century. Does it minimize the Tiller shooting? Maybe. "But by 19th century standards, I'm not even sure his murder qualifies as terrorism. Fools were bucking each other all over the place."

But societal acceptance of political violence aside, Coates said it is important to consider who participated in the 19th century violence:

A core reason an abortion/slavery comparison falls down lay in the actions of the enslaved, versus the inability of action amongst embryos. … Whereas the fight against abortion begins with pro-lifers asserting the rights of embryos, the fight against slavery doesn't begin with the abolitionists, but with the Africans themselves who resisted. …

The anti-abortion fight relies on people with voices speaking for the presumably voiceless. The anti-slavery fight relies, first and foremost, on the enslaved asserting their own freedom. The works and arguments of abolition don't mean much if the blacks, themselves, don't believe in their personhood. Indeed one of the great arguments for slavery was that the blacks actually liked it, that they wanted to be enslaved. As a pro-choicer, I don't think I'd argue that any child would "want" to have been aborted.

Is violence more justifiable when it's self-defense rather than when it is in defense of someone else? That seems a bit at odds with the usual ethical calculus.

Back in January, John Piper considered the question, How is trying to stop abortion different from physically intervening to stop child abuse? "It may not be," he answered. "But I don't think, all things considered, that shooting abortionists accomplishes what you want to accomplish…. Because as soon as you take up violence, they're going to say, "You're doing the same thing that the abortionists are doing." And, therefore, you would never make any headway in this."

Piper talked about his role in the rescue movement of the '80s and '90s. It drew its inspiration not from 19th century abolitionism but from the 20th century civil rights movement:

What brought it all crashing down was that it proved to be impossible – at least here in the Twin Cities – to maintain the kind of humble, meek, lowly, lamb-like demeanor of suffering that would win the American conscience like the Civil Rights Movement. The Civil Rights Movement got traction and was sustained because pictures of Bull Connor and fire hoses and dogs biting black people and mowing down children with fire hoses took the American conscience. "That we will not do!"

But Martin Luther King and the black resistance movement were able to do the miraculous work of not fighting back. … And when the hostilities broke out against them, the media caught it and everything turned around. That did not happen in the pro-life resistance, because pro-life people got mouthy. They were always doing and saying stuff that was ugly. So that's what the media captured. They didn't capture people who were meek and loving and kind being mistreated. They captured pro-life people mistreating. So the whole thing fell apart.

Piper thinks the strategy was counterproductive, but he's still haunted. Not by the protests, but by the lack of a significant alternative. "Abortion remains a moral issue of such huge consequence that, I believe, our grandchildren will look back in a hundred years and condemn us. Me, they'll condemn me," he wrote. "We think we're doing the best we can, but we're probably not. We are so incapable of mounting a full-blown conscientious resistance to the greatest evil in our culture, that all of our strategizing to do political, educational, and crisis pregnancy things will all look inadequate a hundred years from now. They'll just say, ‘You were killing babies!’"

He sounds a lot like David Ruggles, the black abolitionist who led Douglass and hundreds of other slaves to freedom: "The pleas of crying soft and sparing never answered the purpose of a reform, and never will."

Read more about the African-American struggle for freedom in Christian History issue 62, "Bound for Canaan: Africans in America."

Discover the story of Dietrich Bonhoeffer in Christian History issue 32, "Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Theologian in Nazi Germany."