I’ve been listening to Dante’s The Divine Comedy this past week. (The 1891 Charles Eliot Norton translation is this month’s free download from Christian Audio.)

One horrific scene in the Inferno struck me as a literary echo of a more lighthearted moment in J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.

In Rowling, there is a sorting hat. In Dante, there is a sorting monster.

In Rowling, the wizarding school Hogwarts is divided into four residential houses, and a magical hat assigns each first-year student to one of them. When placed on a student’s head, the sorting hat announces where the student belongs: Gryffindor, Hufflepuff, Ravenclaw, or Slytherin.

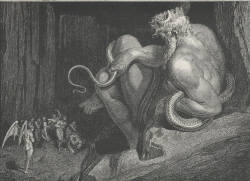

In Dante, hell is divided into nine circles, progressing from circle one, populated by the virtuous pagans who lived without Christianity, on through the realms of the lustful, the gluttonous, the avaricious and prodigal, the wrathful, the heretical, the violent, the deceitful, and finally, in circle nine, the traitors. How are sinners assigned to the proper circle? By the sorting monster named Minos. As Dante tells it,

Thus I descended from the first circle down into the second, which girdles less space, and so much more woe that it goads to wailing. There abides Minos horribly, and snarls; he examines the sins at the entrance; he judges, and he sends according as he entwines himself. I mean, that, when the miscreant spirit comes there before him, it confesses itself wholly, and that discerner of sins sees what place of Hell is for it; he girdles himself with his tail so many times as the degrees he wills it should be sent down. Always before him stand many of them. They go, in turn, each to the judgment; they speak, and hear, and then are whirled below. (Canto V)

Like C. S. Lewis and J. K. Rowling after him, Dante borrowed figures from pagan mythology and imported them into narrative contexts teeming with Christian figures and tropes. Pagan and Christian figures work in complementary fashion to represent longing and fulfillment.

The monster Minos was a mythical king of Crete who after death was said to become a judge of the dead in Hades. That much Dante borrowed. But the act of coiling his tail around himself the precise number of times needed to indicate the circle of hell to which the sinner is to be “whirled below” is Dante’s imaginative invention.

Hades is not Hogwarts and Hogwarts is not hell—indeed for most of Rowling’s series it is effectively defended against invasion by the forces of evil. But both the sorting hat and the tail of Minos represent an orderly universe. Each discerns the corruption or capability of the souls it examines and then places them where they are most suited—either to develop (at Hogwarts) or to suffer (in hell).

Both Dante and Rowling represent the longing for an orderly universe in which talent is cultivated (in the manner in which it specifically ought to be nurtured) and malfeasance is punished (in a manner most fitting to its perversity).

W. S. Gilbert parodied such an orderly universe in his song “A More Humane Mikado.” The “more humane” Mikado announces that instead of executions and arbitrary imprisonments, he will bring in a new order of criminal justice:

My object all sublime

I shall achieve in time —

To let the punishment fit the crime —

The punishment fit the crime;

And make each prisoner pent

Unwillingly represent

A source of innocent merriment!

Of innocent merriment!

All prosy dull society sinners,

Who chatter and bleat and bore,

Are sent to hear sermons

From mystical Germans

Who preach from ten till four.

The amateur tenor, whose vocal villainies

All desire to shirk,

Shall, during off-hours,

Exhibit his powers

To Madame Tussaud’s waxwork.

And so on with exquisitely devised punishments for ladies who dye gray hair yellow or puce, advertising quacks, music hall singers, and billiard sharps. The billiard sharps are forced to play “On a cloth untrue / With a twisted cue / And elliptical billiard balls!”

How exquisite was Gilbert’s sense of justice.

A longing for something like fitting justice persists throughout the Bible and the history of Christian thought. It is implicit, for example, in Christ’s parable of the servant who was forgiven much yet failed to forgive a much smaller debt. We enjoy the jailing of that unforgiving servant precisely because the longing and instinct for such justice is planted within us.

Without this same instinctual longing we would not understand the scandalous character of grace, illustrated the vineyard owner who pays the latecomers as well as those who have worked all day, the prodigal son who gets the fatted calf, and the prostitutes and tax collectors who enter heaven before the religious leaders.

A longing is evidence for the existence of what we long for—whether we lust for junk food or justice. The desire for ultimate justice is a pointer, a sign, a seed, a fragment of evidence that we do well to pay attention to.

* * *

This article was originally posted on the Ancient Evangelical Future blog.