In 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. told an audience at Western Michigan University, “At 11:00 on Sunday morning when we stand and sing Christ has no east or west, we stand at the most segregated hour in this nation. This is tragic.” Sunday morning segregation was especially tragic at two Methodist churches in Philadelphia, separated by one mile and more than 200 years. The two churches, St. George’s and Mother Bethel, reunited for the first time October 25, 2009.

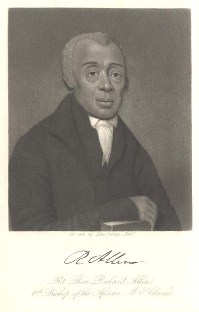

The split between the churches dated back to the late eighteenth century and the career of Richard Allen. Born a slave in Philadelphia in 1760, Allen and his family were sold to a Delaware farmer, Stokely Sturgis, who allowed him to attend church. Slaves’ exposure to Christianity in the early eighteenth century had largely consisted of exhortations to obey their masters, but by the later years of that century, Methodists and Baptists had begun effective evangelism to slave communities. These two churches’ practice of licensing black preachers proved a key to their success but also, unfortunately, brought the racial tensions building in American society in-house.

In 1777, Allen and Sturgis both converted to Methodism. Sturgis became convinced that God would judge slaveholders harshly, so he offered his slaves their freedom for $2,000 each. Allen purchased his and his brother’s freedom in 1783, became a Methodist preacher, and spent the next six years itinerating around Delaware, Pennsylvania, New York, Maryland, and South Carolina. Eventually he worked his way back to Philadelphia. He was invited to serve as assistant minister at St. George’s Methodist Church and to preach publicly in the city’s black neighborhoods. As his popularity grew, so did the black congregation worshiping at St. George’s, much to the consternation of some white members.

In his autobiography, Allen recounted the events that divided the church:

A number of us usually attended St. George’s Church in Fourth street; and when the coloured people began to get numerous in attending the church, they moved us from the seats we usually sat on and placed us around the wall, and on Sabbath morning we went to church and the sexton stood at the door, and told us to go in the gallery. He told us to go, and we would see where to sit. We expected to take the seats over the ones we formerly occupied below, not knowing any better. We took those seats. Meeting had begun and they were nearly done singing, and just as we got to the seats, the elder said, “let us pray.” We had not been long upon our knees before I heard considerable scuffling and low talking. I raised my head up and saw one of the trustees, H— M—, having hold of the Rev. Absalom Jones, pulling him up off of his knees and saying, ‘You must get up — you must not kneel here.” Mr. Jones replied, “wait until prayer is over.” Mr. H— M— said no, you must get up now, or I will call for aid and I force you away.” Mr. Jones said, “wait until prayer is over, and I will get up and trouble you no more.’ With that he beckoned to one of the other trustees, Mr. L— S— to come to his assistance. He came, and went to William White to pull him up. By this time prayer was over, and we all went out of the church in a body, and they were no more plagued with us in the church.

This raised a great excitement and inquiry among the citizens, in so much that I believe they were ashamed of their conduct. But my dear Lord was with us, and we were filled with fresh vigour to get a house erected to worship God in. … We then hired a store room and held worship by ourselves. Here we were pursued with threats of being disowned, and read publicly out of meeting if we did continue worship in the place we had hired; but we believed the Lord would be our friend. We got subscription papers out to raise money to build the house of the Lord.

By this time we had waited on Dr. Rush and Mr. Robert Ralston [two prominent white citizens of Philadelphia], and told them of our distressing situation. We considered it a blessing that the Lord had put it into our hearts to wait upon those gentle-men. They pitied our situation, and subscribed largely towards the church, and were very friendly towards us and advised us how to go on. … Here was the beginning and rise of the first African church in America.

Allen’s church became known as Bethel, or Mother Bethel. Though he had severed ties with St. George’s, he remained connected to the Methodist Church and was ordained its first black deacon in 1799. Over time, though, he became increasingly frustrated with the Methodists’ pattern of subjecting their black churches to white oversight. And so, in 1816, Allen organized the African Methodist Episcopal Church and became its first bishop.

Fast forward to 2009. St. George’s, the oldest Methodist church in America, prepared to celebrate its 240th anniversary. The 250th birthday of Richard Allen was right around the corner. It seemed like the perfect time for a reunion.

St. George’s minister Rev. Alfred Day, quoted in a press release, said, “The incidents that pulled us apart so many years ago do not have to be as powerful as the things that brought the first black and white Methodists together. The experience of God’s Spirit is breaking down barriers instead of erecting them.”

Mother Bethel pastor Rev. Mark Kelly Tyler concurred and looked to the future: “It’s tragic that many of the divisions that led to the splitting of these two congregations over 200 years ago are still alive and well. This worship service is not just about remembering what happened, but we gather in the hope that one day such a service will not even be newsworthy because we have overcome issues of racism, sexism, classism, and all other -isms that separate us from one another and God.”

For now, though, the story is definitely newsworthy.

* * *

For more on Richard Allen, read “You Must Not Kneel Here,” from Christian History issue 62.

Click here to purchase a copy of Christian History issue 62, “Africans in America.”

Public domain image of Richard Allen from the frontispiece of ”History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church” (1891) by Daniel A. Payne via Wikimedia Commons.