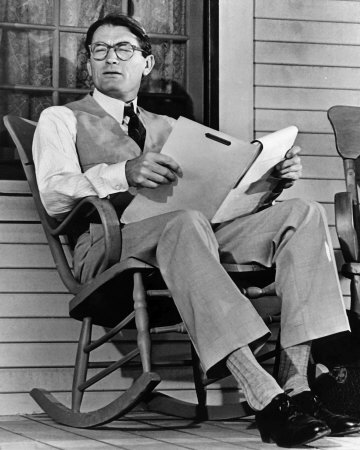

The 50th anniversary this year of the beloved novel To Kill a Mockingbird has many of us remembering the Oscar-winning film and Gregory Peck’s portrayal of Atticus Finch—voted the greatest American hero of 20th century film by the American Film Institute. One key scene shows why this character has become enshrined as an iconic hero and a model of courage: Atticus, alone, facing down an angry, drunken lynch mob late at night with nothing but a newspaper.

Yet when you view Atticus Finch in light of many of our culture’s heroes, something doesn’t add up. Our society reveres success and power. Our heroes prevail in court cases, survive the island, win the big games. Christians seem just as determined to see our view recognized as correct, our argument heard, our sense of entitlement satisfied. Even the heroes of Christian culture seem to be winners these days.

So it’s remarkable that a half century after the publication of Harper Lee’s novel, we still celebrate this small-town lawyer who works out of a meager office and spends his time helping people who can’t afford his services. By today’s standards, Atticus Finch is no winner. We learn at the beginning of the novel that his last two criminal clients were hanged, and —spoiler alert!—his attempt to defend the innocent Tom Robinson (an African-American man falsely accused of rape) doesn’t work out well either.

Sometimes when watching that landmark would-be lynching scene in the movie, I forget that in the book, Atticus’s daughter Scout tells us that her father’s hands were shaking. Plain fear was shooting out of his eyes when she approached him in front of the mob. How could we forget that he allows the bad guy, Bob Ewell, to spit in his face and curse him in public—he simply wipes his face and walks away.

Certainly, onlookers may have made assumptions about Atticus’ ability to handle himself. In the courtroom, he steadily draws out the truth without raising his voice, always treating Tom’s despicable accusers with respect they certainly did not deserve. He tips his hat in kindness to the old lady, Mrs. Dubose, who curses and taunts his children day after day. Known as the “best shot in Maycomb County,” he refuses to pick up a gun to protect himself. He takes on a court case that sets him at odds with his community and places his children’s well-being in jeopardy, but tells his daughter that no matter how bad things get she should always remember that these people are their neighbors. His actions aren’t expedient, clearly aren’t in his best interests, and on top of it all—Atticus does not win. Not the day, the argument, the fight, or even the court case.

So why are we so drawn to this character as a hero?

I believe it’s because his courage is so grounded in faith. When Scout asks him why he must defend Tom Robinson, he simply responds, “I couldn’t go to church and worship God if I didn’t defend that man.” Atticus grasps something that I often forget in my own life—that my daily choices have an eternal impact. This is why Atticus can place himself between the mob and an innocent man—teaching us that courage isn’t the absence of fear but the absence of self. It is where he draws the inner resolve to walk away from Bob Ewell’s assault. It is why he understands the importance of maintaining a connection to his neighbors—even when their views are despicable.

Atticus teaches us that courage has nothing to do with winning. “I wanted you to see what real courage is,” he tells his children. “It’s when you know you’re licked before you begin but you begin anyway and you see it through no matter what. You rarely win, but sometimes you do.”

Such heroism is evidence of something divine running through the DNA of humanity. A God-given courage that recognizes our actions might impact eternity more significantly than they ever will in the here and now—that we may lose the argument, the day, even the trial—but we have still advanced the kingdom. This kind of courage isn’t about winning, but making the decision to do what is right—no matter the cost.

***

Matt Litton, author of The Mockingbird Parables(Tyndale), lives in Cincinnati with his wife Kristy and their four children.