"This Land Is Your Land," Woody Guthrie's most famous song, has been sung by school children, scouts, church choirs, and war veterans. Its message of freedom and hope make it quintessential Woody. So does its undercurrent of protest and equality.

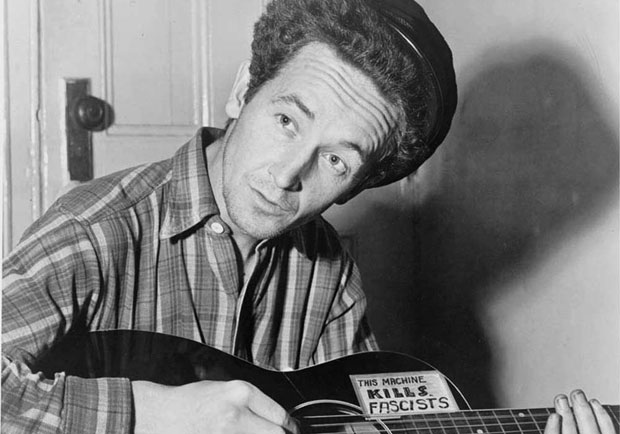

Woody Guthrie

Guthrie wrote the song in 1940 as an angry response to Irving Berlin's popular "God Bless America." If God blessed America, why were there so many poor and downtrodden people littered across its land, still reeling from the Great Depression and Dust Bowl devastation? His original handwritten lyric closed the song with "One bright sunny morning in the shadow of the steeple / By the relief office I saw my people / As they stood hungry, I stood there wondering if / God blessed America for me." Below the lyrics he wrote, "All you can write is what you see." (Read the complete lyrics here.)

Woodrow Wilson Guthrie was simple and earthy, political and spiritual. His music was infused with God and country and the humanity in between, especially the downtrodden and oppressed. Those were Guthrie's people: the hobos and migrants and laborers and union organizers. The weather-worn Okie minstrel was one of them. He was their voice for justice and dignity in the 1930s and '40s.

He was also arguably the most important figure in American folk music. Pete Seeger? Guthrie was a mentor, collaborator and bandmate in The Almanacs during the '40s. Arlo Guthrie? Woody was his father. Bob Dylan? Guthrie was his hero. It was a pilgrimage to visit the seriously ill Guthrie that brought the 19-year-old Dylan to New York City—and Woody's circle of musician friends who helped open doors into the performance scene for Dylan. Trace Dylan's marriage of folk with rock and roll and, moving forward, you follow the family tree through Springsteen and Mellencamp to today's Americana neofolk revival in all of its various combinations.

The Mermaid Avenue cover

To mark the centennial of Guthrie's birth, two excellent new releases open the doors to his music and the man behind it. The recently released Mermaid Avenue: The Complete Sessions pairs Billy Bragg and Wilco. And New Multitudes (released in February on Rounder Records) brings together Jay Farrar (Son Volt, Gob Iron, Uncle Tupelo), Yim Yames (aka Jim James of My Morning Jacket, Monsters of Folk), Will Johnson (Centro-matic, South San Gabriel), and Anders Parker (Varnaline, Gob Iron).

These albums aren't mere tributes. All the lyrics are Guthrie's; they came from 3,000 unrecorded songs he left when he died in 1967. Many had been originally scratched on paper scraps stuffed in Guthrie's pockets as he hopped freight trains and followed the migrant masses down Depression era byways. Woody's daughter Nora Guthrie invited select musicians to cull from the collection and create the music to give them wings.

Mermaid Avenue is the more comprehensive project, including 47 songs and the 1999 documentary film Man in the Sand, which offers insight into the recording process and Guthrie's life. Volume I and Volume II released in 1998 and 2000 respectively; the first was Grammy nominated for Best Contemporary Folk Album. The 17 newly released songs of Volume III were recorded at the same time. New Multitudes is more recent, but both projects sound fresh and relevant.

Crying in the wilderness

It's a testimony to their timelessness that Guthrie's lyrics fit so comfortably into these newer Americana rock arrangements. Credit that to the raw humanity at their core. Woody's words narrate the modernization of America through the eyes of its laborers and casualties. He was one of them. But with his music he was also a voice crying in the wilderness for social change, just more Walt Whitman than John the Baptist.

The injustices Guthrie tackled are still among us. What better time for the voice of a prophet from the Great Depression than during our nation's greatest economic upheaval since? When has raising a voice for the oppressed been more necessary than in a day when we can readily see the unfair sufferings of fellow humans around the entire world, not just within our own borders?

The practical answers to those questions can be complex, but they must be confronted by those who follow Jesus. Guthrie confronted them with his music and socialist political views. He rejected any forms of religion for most of his life. With his fierce independent streak and womanizing—even while he was married—ways, he clearly didn't want anyone telling him how to live. But he was more interested in social change for the here and now than the wait-for-heaven passivity he saw in Christianity. Injustice meets spiritual frustration in "Union Prayer" (covered on Mermaid Avenue, Vol. III), where Guthrie asks, "Will prayer give jobs at honest pay? / Will prayer bring stomachs full of food? / Will prayer make rich treat poor folks right? / Will prayer take out the Ku Klux Klan?"

Still, Guthrie maintained an ongoing fascination with Jesus and his teachings about the poor. "Christ for President," on Mermaid Avenue, blends his ideals: "Let's have Christ our President / Let us have him for our king / Cast your vote for the Carpenter / That you call the Nazarene / The only way we can ever beat / These crooked politician men / Is to run the money changers out of the temple / Put the Carpenter in."

The New Multitudes cover

Sincere? Satirical? Hard to say, but it lines up with Guthrie's preoccupation. "It ain't just once in a while that I think about this man, it's mighty scarce that I think of anything else," he wrote about Jesus, according to the biography This Land Was Made for You and Me.

Later in life, Guthrie did embrace Jesus after he had been hospitalized with Huntington's disease at age 42. The illness that degenerates the brain and nervous system was barely known then and little understood. The ramblin' musician was hospitalized for the final 15 years of his life. He wrote music until the disease froze his body and stole his physical and mental abilities to do so. Mermaid Avenue and New Multitudes' songs from that period reflect the shift of Woody's perspective. "Ain't Gonna Grieve" and "Blood of the Lamb" turn toward heaven. And "No Fear" confidently stares down looming death: "I'm here on my deathbed / Takin' my last breath / 'Cause I got no fears in life / I got no fears of death."

The music making its way to new ears through projects like Mermaid Avenue and New Multitudes continues to challenge and prod as much as entertain and uplift. Guthrie never shied away from despair, but he always believed hope could overcome it. His songs are still delivering that message no matter who's singing them, as these lyrics from "Hoping Machine" will attest:

"Don't lose your grip on life and that means / Don't let any earthy calamity knock your dreamer and your hoping machine / Out of order."

Photo of Guthrie by Robin Carson, courtesy of Woody Guthrie Archives.

Copyright © 2012 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.