Four and a half months into Mohamed Morsy's presidency, much of Egypt's democratic transition is still on hold. Parliament remains dissolved. A new constitution is still pending, beset by legal challenges. In this political limbo, Morsy has appropriated even more power than former dictator Hosni Mubarak enjoyed before the January 2011 revolution.

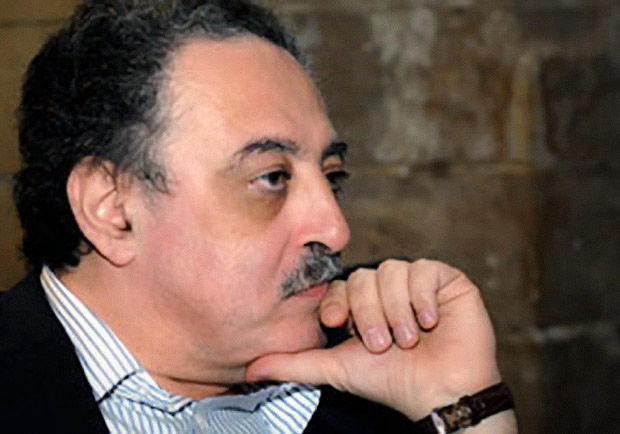

However, alongside Morsy in this limbo is Samir Marcos, a Coptic intellectual serving as assistant president for democratic transition.

As a Coptic Orthodox Christian, Marcos joined a female academic, a Muslim Brotherhood member, and a Salafi politician as one of four diverse members of Morsy's presidential team. The exact role of an assistant president, however, has been left vague. Marcos is greater than an advisor but less than a vice president—the position Morsy promised to give a Copt and a woman when he assumed office in June.

For his part, Marcos believes he has real authority to change the Egyptian system from Pharaonic to democratic, he told Egyptian newspaper Sharq al-Awsat. He told another newspaper, al-Ahram, "Either I make a difference or I leave."

This is exactly the attitude proposed by Hany Gaziri, a veteran political and Coptic activist who has battled both Mubarak and the Muslim Brotherhood for years. He encouraged Marcos in his new responsibility.

"We told him, 'Accept the position and be involved in the administration, and we will be behind you and support you. But if you feel you are being marginalized and not listened to, resign and make this clear to everyone,'" said Gaziri.

"In the past, the government only chose Coptic figures who most Copts hated," he continued. "But the choice of Marcos honors us and he will represent us well."

Marcos is esteemed by many Copts, including Safwat el-Baiadi, president of the Protestant Churches of Egypt. "[Marcos] is a good writer and thinker," he said. "Because of this, he was chosen."

During the 1990s, Marcos served as the assistant secretary-general of the Middle East Council of Churches. He left the organization to focus more directly on interreligious relations, and became head of the Egyptian Foundation for Citizenship and Dialogue. After the revolution, the military council appointed him deputy governor of Cairo.

Not all Copts are happy, however, as many feel his appointment is only symbolic.

"The Muslim Brotherhood's reputation in the international community will improve with him there, but Copts will not gain anything," said Mamdouh Nakhla, head of the Word Center for Human Rights. "It is very difficult to change the regime from the inside."

George Messiha, one of only seven Coptic members of the now-dissolved parliament, holds a similar opinion. He hopes Marcos's ideas will translate into real action, but is skeptical.

"[Marcos] is there for political reasons, and it is the same with many others," said Messiha. "It is done to keep Christians from complaining they have no one in high positions."

Even more concerned is the Maspero Youth Union, a Coptic activist group that rejects any cooperation with the Muslim Brotherhood, and thus the presidency.

"We will coordinate with Marcos and give him reports if requested," said Mina Magdy, deputy coordinator for the group. "But we disagree with him accepting the post."

By contrast, Yousef Sidhom, editor-in-chief of the influential Coptic newspaper Watani, believes the appointment shows real openness to Copts on the part of Morsy. Thus, it should not be turned down.

"The most unwise thing to do would be to refuse working with the administration due to its ties to the Muslim Brotherhood," he said. "Despite our different perspectives concerning the civil state, we must maintain at least the minimum of dialogue so that we can work together for the good of Egypt."

As for the democratic transition, Sidhom like others is left in limbo to watch and wait.

"What [Marcos] will be asked to do, and whether he will be able to do it—this remains to be seen."

Jayson Casper is the editor of the Episcopal Diocese of Egypt's online bilingual magazine Orient and Occident. He blogs on Egyptian politics, religion, and culture at A Sense of Belonging.