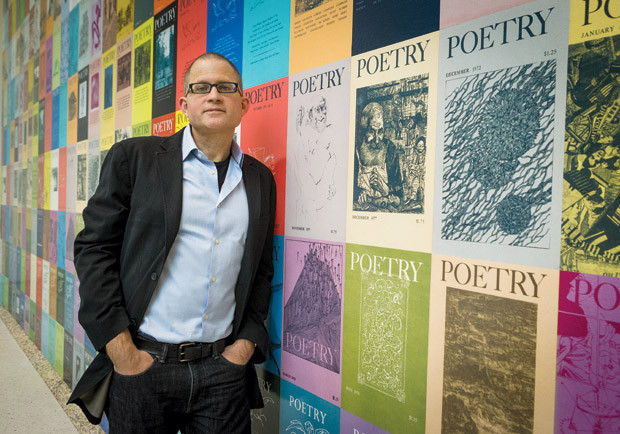

In the afternoon of his 39th birthday, less than a year after his wedding day, poet Christian Wiman was diagnosed with an incurable cancer of the blood. Wiman, who announced Wednesday that he will step down in June as editor of Poetry magazine, the oldest and most esteemed poetry monthly in the world, had long ago drifted away from the Southern Baptist beliefs of his upbringing. But the shock of staring death in the face gradually revived a faith that had gone dormant (a story he first told publicly in a 2007 article for The American Scholar).

Wiman’s new book of essays, My Bright Abyss: Meditation of a Modern Believer (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), took shape in the wake of his diagnosis, when he believed death could be fast approaching. These writings come from someone who is less a cautious theologian than a pilgrim crying out from the depths. They divulge the God-ward hopes (and doubts) of an artist still piecing together a spiritual puzzle. San Francisco-based lawyer and author Josh Jeter corresponded with Wiman about his new book, his precarious health, and the ongoing challenge of belief in God.

How did you arrive at your Christian faith?

I was raised in West Texas as a Southern Baptist, in a culture and family so saturated with religion that it never occurred to me there was any alternative until I left. Then it all just evaporated in the blast of modernism and secularism to which I was exposed in college. Or, it didn’t evaporate, exactly, because I never would have called myself an atheist. But religious feeling went underground in me for a couple of decades, to be released occasionally in ways I never really understood or completely credited—in poems, mostly.

‘There’s no question that illness has brought a great urgency to my work: One speaks differently when standing on a cliff.’—Christian Wiman

Then about 10 years ago I fell into despair. There is no other way to say it, really, nor do those words do anything but hint at the abyss. Whether it was cause or effect, I went through a writing drought unlike anything I had ever known—three years of it. In the midst of this—miraculously, it now seems to me—I fell suddenly and utterly in love with the woman who is now my wife. I still couldn’t write, but the despair was blasted like a husk away from my spirit.

We found ourselves saying little prayers together before dinner. They were almost jokes at first, and then, increasingly, not. We’d been married about eight months when I got a surprise diagnosis of an incurable cancer, and the encroaching darkness demanded that the light I felt burning in me acquire a more definite and durable form. One Sunday morning we wandered into a church. A couple of days later I started to write. I don’t think it’s quite accurate to say that I had a conversion or even a “return” to Christianity. I was just finally able to assent to the faith that had long been latent within me.

You have three vocations: poet, editor of Poetry magazine, and, most recently, spiritual essayist. How did you decide to begin writing spiritual essays?

I’ve always written prose, and I can now see how God’s absence—or, more accurately, my refusal to admit his presence—underlies all of my earlier work (poems as well).

But you’re certainly right to point out a change. My work—prose and poetry—is still full of anguish and even unbelief, but I hope it’s also much more open to simple joy. The theologian Jürgen Moltmann once wrote that all theology, especially a theology of hope, had to be conducted “in earshot of the dying Christ.” Abundance and destitution are both aspects of God—or, more accurately, aspects of our experience of God.

Soon you will release a set of essays. How has your turn to faith shaped or influenced these essays?

After my diagnosis, I wrote a short piece trying to make sense of all that had happened to me. It was published in a relatively small magazine, The American Scholar, but the response to it was pretty overwhelming. I began to realize there was an enormous contingent of people out there who were starved for new ways of feeling and articulating their experiences of God. I wanted to have a conversation with these people.

I also wanted to figure out my own mind. I knew that I believed, but I was not at all clear on what I believed. So I set out to answer that question, though I have come to realize that the real question is how, not what. How do you answer that burn of being that drives you both deeper into, and utterly out of, yourself? What might it mean for your life—and for your death—to acknowledge the insistent, persistent call of God?

You have had some very difficult health issues the past few years, and according to one essay, have recently been “close to death.” How is your health now? And what have your health struggles meant for your work?

I’ve been through a multitude of treatments, culminating in a bone-marrow transplant last fall. There’s no question that illness has brought a great urgency to my work: One speaks differently when standing on a cliff. Then again, I have always had little patience for art that is not elemental, art that doesn’t take on the major questions of our existence. Perhaps my own inclinations have simply been intensified by my illness.

As for that illness, it’s gone. For now. I haven’t felt this healthy in eight years. I hope I am now faced with the difficult task of learning to live without my familiar miseries. “Our torments also may, in length of time, Become our elements,” says John Milton. “[T]hese piercing fires [a]s soft as now severe.” There is always some devil in us—that’s a demon speaking the lines above—who makes us think we love or need our pain.

Sometimes your essays feel like you are arguing with yourself. Do you write them for yourself or others?

I’ve never thought of my essays like this, but I see immediately that you’re right. W. B. Yeats defined rhetoric as the quarrel we have with others. Poetry, he said, comes out of the quarrel we have with ourselves. Prose isn’t poetry, obviously, but I’ve always felt the two arts to be raveled up with one another for me.

I read a lot of theology, even though I am almost always frustrated by it. Thomas Merton once said that trying “to solve the problem of God” is like trying to see your own eyes. No doubt that’s part of it. There is something absurd about formulating faith, systematizing God. I am usually more moved—and more moved toward God—by what one might call accidental theology, the best of which is often art, sometimes even determinedly secular art.

I am moved by works of art that don’t so much strive to make meaning as allow meaning to stream through them: Bach, certain poems by T. S. Eliot, the novelist Marilynne Robinson, the late work of the American sculptor Lee Bontecou, even less conventional religious writers like Simone Weil or Sara Grant. People can occasionally embody and enact this kind of meaning as well—we are, after all, works of the very greatest Creator’s hands.

How much is spiritual experience—prayer, solitude, and the like—a part of your artistic process?

I think poetry is how religious feeling survived in me during all those years of unbelief, and it remains the most intense experience I have of another order of being entering my own. But poems are not contemplative or peaceful times for me; they’re chaotic and can wreck my life for a while. They’re also few and far between, and you can’t (or I can’t) build a spiritual life on that kind of intermittent intensity.

So I try to pray every day, usually in a little chapel near where I work, sometimes in a cathedral because I like the huge estrangement of it, the volatile silence. I feel no connection between prayer and poetry, except for the poems that I have written as prayers. Poetry is a much more powerful experience for me than prayer, but I feel this to be a weakness in me. I’m still just learning how to pray.

In your essays, you often appeal to the work of Christian mystics (like Meister Eckhart, Thomas Traherne, George Herbert, Marguerite Porete, Weil). What draws you to the mystics?

Partly I feel envy. I want to be taken over by God. I want to have the kind of disciplined inwardness that allows the ego to be annihilated. I want the kind of revelation that precedes all doctrine and dogma, is the reason for all doctrine and dogma. Christ’s life is one long revelation; everything after that merely grows up from it.

But then, too, all of these writers have an artistic consciousness. I understand the language they speak, though I don’t quite speak it myself, or maybe speak a different dialect. The energy of art may be prior to religion, but religion, paradoxically, is a way of sustaining and surviving the psychic storm of that original energy (just as ritual and doctrine are ways of stabilizing and preserving the awful power of mystical revelation). Art for its own sake, art that has no answering “other,” will eventually eat you alive.

You have written that one measure of a genuine spiritual experience is the extent to which it “demands uncomfortable change.” What kinds of “uncomfortable changes” have you experienced in your life?

That’s what my wife always asks me!

I would like to think of this new book as a viable answer to your question, but solitary writing is quite natural to me, and we should be suspicious when God’s call conforms so neatly to our own inclinations.

More relevant, maybe, are the many speaking engagements, including sermons, I have taken on at religious schools and organizations in the past few years. This is new to me and, while very gratifying, has at times been quite discomfiting. I have also become deliberate about being open and honest about my thoughts of God. Maybe not so honest in secular settings. That, too, has provoked some useful but uncomfortable exchanges.

Still, the question is a thorn in my brain. I feel that I spend too much time agonizing over what faith might mean, rather than simply acting in accordance with my instincts. Dietrich Bonhoeffer once wrote that only the person who obeys believes. It is a hard road, but the right one. I will probably end up as a preacher after all.

Your faith does not come across as breezy in your essays, which you occasionally grace with levity. For example: “If I ever sound like a preacher in these passages, it’s only because I have a hornet’s nest of voluble and conflicting parishioners inside of me.” Does your faith ever express itself as peace?

Rarely, which I see as a weakness. I do feel that some people may be called to unbelief—or what looks like unbelief—in order that faith may take new forms. Emily Dickinson is a good example of this, or Albert Camus. But I also believe that God requires every last cell of yourself to bow down. Or perhaps that verb, requires, is wrong, or that it’s God doing the requiring: It’s more like your nature requires, in order to be your nature, that every last cell of yourself bow down. There is still some satanic pride in me, for which I pay a high price.

And yet, I have certainly experienced peace in poems that in their sheer givenness seemed to reveal something of God to me. I have written poems that begin in great anguish and explode into joy. As psychically difficult as the poems may have been to write, certainly I have felt peace and presence in their wake.

There are other moments, too, which are simply moments of life. Simply! I think of the poet Paul Eluard: “There is another world, but it is in this one.” I have 3-year-old twin daughters. It would be disingenuous in the extreme for me to pretend that they don’t at times drive all thought of God out of my head and make me want to write a series of sonnets in praise of celibacy, but it would be equally insane for me not to acknowledge that they are the source of my greatest happiness. Father Zossima, in The Brothers Karamazov, defines hell as “the inability to love.” I have known that hell, and I should probably spend my remaining days thanking God that I am free of it.