Jeff Chu describes himself as gay, partnered, relatively politically conservative, and a member of a relatively liberal New York City congregation in a relatively conservative denomination (Reformed Church in America). He is far from his Southern Baptist upbringing but, once in a while, finds himself wondering "whether my homosexuality is my ticket to hell, whether Jesus would love me but for that, and how good a Christian could I be if I struggle to believe that God loves me at all." For Chu, and for many Christians of all sexual orientations, homosexuality is a "spiritual wedge issue," one of those topics or teachings that "gnaw at us and what faith we may have left."

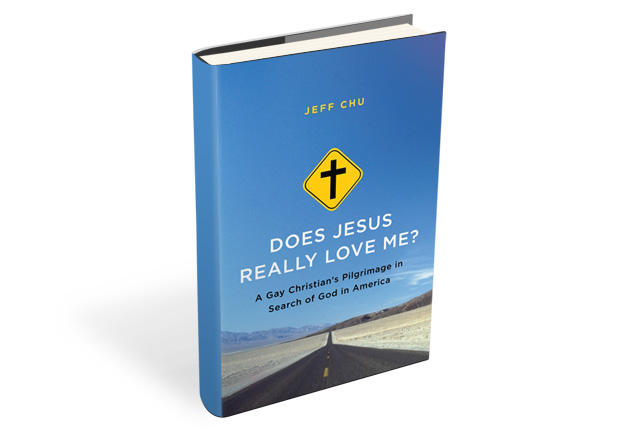

Does Jesus Really Love Me?: A Gay Christian's Pilgrimage in Search of God in America

Harper

368 pages

$25.90

Chu is also a journalist, and the author of Does Jesus Really Love Me? A Gay Christian's Pilgrimage in Search of God in America (Harper Collins). The book chronicles a year-long pilgrimage devoted to exploring homosexuality in U.S. churches. On a more personal level, Chu is confronting "the ghosts who still haunt my heart." The book is a unique mix of journalism, memoir, and religious commentary, a style that is sometimes persuasive, but other times confusing, when journalist turns commentator, or spiritual seeker turns interviewer. He visited dozens of churches in various denominations, but all described are Protestant. He misses Roman Catholics, Orthodox, and most (but not all) Protestant mainline groups, favoring a wide variety of evangelical and/or conservative groups and people. He interviewed dozens of people, some of them everyday folk, others more in the public eye, including Ted Haggard, Jennifer Knapp, Mary Glasspool, and even Fred Phelps.

The book is organized in four parts: doubting, struggling, reconciling, and hoping. The first three seem to contain the Christians and churches that display that approach to homosexuality. "Reconciling" is clear enough as a category, but "doubting" and "struggling" seemed both to include Christians who find homosexuality to be contrary to God's will, and express that theology in various ways. The difference between "doubting" (doubting what?) and "struggling" (struggling with what?) isn't clear. It's also not clear why Westboro Baptist Church and Harding University (a conservative Christian college with a "queer underground") belong in the same category, nor in what respect Fred Phelps and his followers may be described as "doubting" (they express none whatsoever in their interviews with Chu). The fourth section of the book, "hoping", completes the story of Gideon Eads, a young Christian who chronicles his coming out in real time over the course of Chu's pilgrimage.

Different Approaches

Part One describes churches and Christians from Tennessee, Maine, Kansas, and Arkansas, all of them confident that homosexuality is against God's will. That belief is expressed very differently, from Fred Phelps's hatred to Harding University's attempts to foster open, civil campus conversation. Chu's declaration of open-hearted spiritual pilgrimage falters here; his personal quest lacks stakes, other than emotional ones. He doesn't seem open to overhauling his theology, sexual orientation, personal life, or church affiliation, especially in response to conservative theology. This is fine, certainly, but the book's title and opening imply a deeper level of questioning than is evidenced in the narrative. This section reads more like a journalistic inquiry than personal pilgrimage, which works well enough; Chu is mostly even-handed in his descriptions of various Christians, and is able to facilitate long interviews and repeated interactions with people whose beliefs and actions are disagreeable or even aggressively offensive. Unfortunately, at times he can't resist referring to conservative beliefs or even individuals as "weird" or "bizarre," labels that he doesn't dole out to the group of "reconciling" churches and people.

Chu begins this section with one major theme: that among people leaving Christianity these days, judgmental behavior is the strongest factor spurring their departures. Secondly, he expresses surprise that Christian theology, even an idea as traditional as "God intends sex only for a marriage between a man and a woman," is expressed in such divergent ways (not to mention the many alterations of tradition). "It's almost as if people are speaking entirely different languages. And it's almost as if people are preaching totally different faiths."

In Part Two ("struggling") he describes Exodus International's approach to homosexuality, a mixed-orientation marriage, and the celibacy of a same-sex oriented man. Included here is transcript of an interview with Ted Haggard, who, after some strangely aggressive words at the beginning of the interview, settled down into some thoughtful discussion of his recent years. The accuracy and nuance with which Chu describes Exodus ministries is remarkable, given the organization's rapid changes of late. The story of 57-year-old Kevin Olson, life-long celibate with same-sex attraction, is wonderful. Chu engages Olson's story with Wesley Hill's (Washed and Waiting), raising good questions for Christians who advocate celibacy as the only biblical option other than marriage between a man and a woman. Though Olson is lonely and restrains himself from forbidden intimacy, he also conveys to Chu that celibacy is more than inaction; it's also an active pursuit of eternal joy and contentment in his relationship with God.

Part Three ("reconciling") describes a variety of progressive and/or liberal Christians and churches. Some don't rewrite their theology or view of the Bible; rather, they are shifting their "posture" from judgment to love. For example, David Johnson's ministry in South Carolina focuses on inviting gays and lesbians into a living relationship with God. He sees his role as reminding them that "God loves you no matter what," letting the implications for their sexual lives get worked out over time, rather than predetermining them up front. Others more explicitly alter tradition; Chu visits the Metropolitan Community Church of San Francisco and other locations on the "reconciling" extreme. He describes them as celebrating people more than focused on God, and says some participants even report an "oversexualized atmosphere." His conservative background shines through when he concludes that "by building the church as if it were fundamentally about making ourselves feel better, I wonder if we also totally miss God."

With Westboro Church at one extreme, and MCC-San Francisco at the other (a strategic juxtaposition that inclusion of more mainline churches would have nuanced), Chu finds a happier medium at Highlands Church in Denver. Because he decided to include gays in positive ways in theology and leadership, founding pastor Mark Tidd lost his Christian Reformed Church credentials and his church planting support. Nonetheless, Highlands Church is thriving. Jenny Morgan, co-pastor and partnered lesbian, describes it as "a deeply Christ-centered, deeply biblical church that is okay with the gays." This approach rings true for Chu, who describes it as "progressive evangelicalism," though traditional evangelicals likely wouldn't call it that. Interestingly, Chu says that homosexuality isn't, and shouldn't be, the focus of such a church. What most deeply resonates with him is that people are encouraged to "bring their whole selves, not just their sacred stances but also their profane fears and insecurities. They are called to do what is uncommon in the church: question boldly, without fear and in confidence." This ethos, and the Christ-centeredness of the church, seems to impress Chu more than the theological affirmation of homosexuality.

An Unfortunate Turn

In Part Four, after describing the coming out of Gideon Eads, a heart-rending narrative that ends on an open-ended note, the book takes an unfortunate turn. The last few pages conclude that "if the church is supposed to be the body of Christ, then what I saw on my trip were our Lord's dismembered and terribly dishonored remains." Chu then describes the reasons for the "diminution" of his faith: pastors (too cowardly), words (used too thoughtlessly), and people (not loving enough). His words might be more powerful if read aloud in a testimony, or written in an op-ed essay or blog post. Positioned at the end of a journalistic inquiry, they come across as a diatribe that undercuts the sincerity of the pilgrimage. (These flaws weren't newly revealed to him during his quest; they were a large part of what distanced him from conservative Christianity many years ago.)

He concludes that God is more important than the church, but takes the "spiritual but not religious" argument to an extreme, stating that a renewed belief in "God—my God" is the most important thing he takes away from his journey. "My God isn't simply the God I believe in but the God I want to believe in and need to believe in." Crafting highly personalized views of God may soothe our church-inflicted wounds, but responding to fracture within the church with personalized gods hardly seems the path toward unity. I wish he had found more hope in the examples of Christians learning, engaging in difficult conversation, and building relationships across perceived chasms of theological, sexual, and other differences.

Does Jesus Love Me? is an essential survey description of homosexuality in U.S. churches today that should be read by church members and leaders, and people who care about how U.S. Christians engage with sexual minorities and related issues. No reader could possibly agree with every Christian or church, because such vast variety is described; every reader will be challenged to listen to those with whom they disagree, and recognize their group as one among many in American Christianity today. The stories would make good conversation starters, as points of comparison and contrast to personal and church-wide spiritual journeys.

Jenell Paris is professor of anthropology at Messiah College, and the author of The End of Sexual Identity: Why Sex Is Too Important to Define Who We Are (InterVarsity Press).