In this series

(MSN) Protestant leaders in Bolivia once welcomed how President Evo Morales reduced religious discrimination by severing the Andean government's longstanding ties with Roman Catholicism. However, now they fear that pre-Colombian animism is replacing Catholicism as the official state religion.

Church leaders are trying to revoke a new law they say aims to "impose contrary beliefs" and "denies us the right to be a church."

The National Association of Evangelicals of Bolivia (ANDEB) will file suit before the Plurinational Legislative Assembly demanding that Law 351 be revoked as unconstitutional; Christian leaders argue its re-registration requirements restrict the "rights and religious freedoms of churches."

The law stipulates a standardized administrative structure for all "religious organizations" that church groups must adopt.

"This would force churches to betray their true ecclesiastical traditions," Ruth Montaño, legal advisor and former board member of ANDEB told Morning Star News (MSN). "The measure deprives them of any autonomy to follow their original faith convictions."

Churches failing to complete the re-registration within a two-year period would lose their legal right to exist. The ANDEB suit charges that Law 351 aims to "control" churches and "impose contrary beliefs" upon the Christian faith and "denies us the right to be a church."

ANDEB organized protest marches by an estimated 20,000 people on Aug. 17 in five cities throughout the country to state their opposition to the policies of President Evo Morales's administration.

At the heart of the demonstrations was opposition to Law 351 for Granting of Juridical Personality to Churches and Religious Groups, passed in March. The statute requires all churches and not-for-profit organizations to re-register their legal charters with the government. This involves supplying detailed data on membership, financial activity and organizational leadership.

"They want to control the activities of the evangelical churches," Agustín Aguilera, president of ANDEB, told the Santa Cruz newspaper El Deber. "Article 15 (of the law) would force all religious organizations to carry out our activities within the parameters of the 'horizon of good living,' which is based on the [ethnic] Aymara worldview. This is an imposition of a cultural and spiritual worldview totally foreign to ours."

[Editor's note: Article 15 says the practices of registered religious organizations must advance the Aymara concept of "living well." The Spanish text reads: "Las organizaciones religiosas y espirituales son el conjunto de personas naturales, nacionales y/o extranjeras que realizan prácticas de culto y/o creencias para el desarrollo espiritual y/o religiosas en el horizonte del Vivir Bien, cuya finalidad no persigue lucro."]

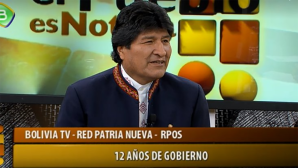

President Morales identifies himself ethnically as Aymara, although he also claims to be a "grassroots Catholic." Aymara-speakers form the second largest indigenous group in Bolivia, after Quechuas.

Government officials are not granting legal status to newly formed evangelical churches, pending approval of regulations being formulated by the Registry Office of Worship, according to ANDEB leaders. The proposed statutes violate the constitution in terms similar to those of Law 351, they say.

Protestant leaders assert that, taken together, the new measures grant the government regulatory power over the internal affairs of churches to the point of defining what is and is not a church.

Ironically, Morales assumed office in 2006 with promises of greater religious freedom. The first indigenous Andean to be democratically elected president of Bolivia, he abolished the historic domination of the Roman Catholic Church over religious affairs.

The constitution of February 2009 established a "secular state" designed to be neutral in matters of faith and conscience. The country's Protestant Christian population, which had long sought church and state separation, initially welcomed the new political order. They assumed a secular state meant the end of religious discrimination.

Protestant leaders now fear, however, that pre-Colombian animism is replacing Roman Catholicism as the official state religion. Morales's administration routinely invites amautas (folk doctors) to bless government ceremonies, instead of Roman Catholic priests as per traditional protocol.

At Morales's invitation, ANDEB leaders have been working since 2010 to formulate a law to guarantee freedom of religion. They believe the legislation is needed to ensure that constitutional guarantees be respected.

Their effort so far has gone unrewarded. Despite his repeated public statements that freedom of worship is a priority, Morales has yet to follow through on his promise to introduce the religious liberty legislation to parliament.

Nor has he responded to a letter ANDEB officials presented him last year asking for an audience to discuss the religious liberty bill. Instead, Morales signed the restrictive Law 351 over evangelical objections.

"Along with the suit to revoke Law 351, ANDEB attorneys plan to introduce the Law for Religious Liberty to the Plurinational Legislative Assembly," Montaño said. "And we expect a positive response from congressional members."

At the same time, ANDEB is initiating a national petition campaign and consultations with parliamentary representatives in every department (state) of the country, she said.

"Should all else fail, we plan to file an 'abstract of unconstitutionality' against Law 351 before the Constitutional Tribune in order to protect our rights," Montaño said.

As in most South American countries, Protestant worship was banned in Bolivia until about 100 years ago. Today evangelical Christians represent 16 percent of the country's population of 10 million, according to Operation World.