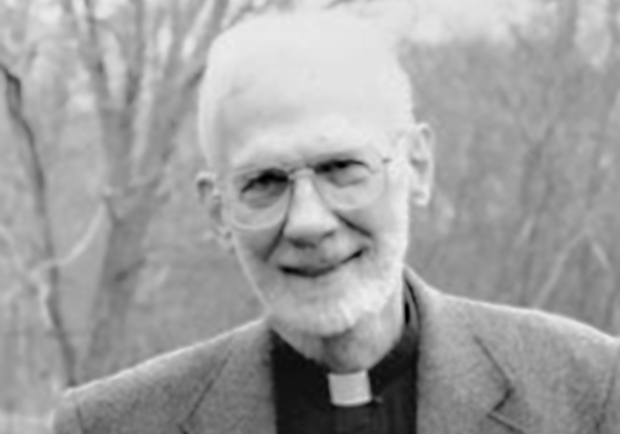

Father Robert Farrar Capon, the Episcopal priest and author of many books, most notably The Supper of the Lamb, died last week at the age of 88.

Though I did not know of him or his work until I was an adult, he was known to many of the people among whom I grew up and lived and worshiped, though not, to them, as a writer, but as a beloved if eccentric member of the community. He lived for many years on Shelter Island, New York, which is just a short ferry ride across the bay from the town where I grew up; it's a place I have been countless times. When, as an adult, I checked Father Capon's books out of the local library, I noticed that they were signed with a barely legible flourish and a cross. "He's quite a character," Jean, the librarian, also a Shelter Islander, said. "I haven't seen him around in a while, though. I don't even know if he's still alive."

A few days later, while flipping through the 'C's in the local yellow pages to find the number for the Chinese takeout restaurant—in my hometown it's still easier to find numbers that way than via Google; and, foodie or not, weekly Chinese takeout is a family tradition—my eyes fell on "Capon, Robert F." I scribbled the number down, and called the next day.

Mrs. Capon ("CAY-pun. It's CAY-pun, honey," she told me gently, after I called her "Mrs. Ca-PONE," as if she were the wife of the gangster) talked with me for nearly an hour. I told her how much her husband's books had meant to me, and that I was writing a book of my own on faith and food. Would Father Capon be up for a short visit and a chat?

Sadly, he wouldn't be: "do you know what hydrocephalus is, honey? He's got water on the brain." Though he was sporadically coherent, he couldn't be left alone and wasn't really up for visitors. Still, every day, she told me, they celebrated the Lord's Supper, and she cooked for him. "That Peapod delivery is so wonderful," Mrs. Capon told me. "I can get what I need to make meals and I don't have to leave him." He loved being read to, she said; Sarah Young's Jesus Calling seemed to reach him; his face broke into a rare smile of delight when she read from it. From Mrs. Capon's description of their routines, worshiping and eating seemed to form the foundation of their life together—appropriately enough for a man known for his work on theology and cooking.

Mrs. Capon was a bit surprised when I told her that I particularly liked Father Capon's first book, Bed and Board: Plain Talk About Marriage, an unconventional and, though dated, delightful celebration of the joys of marriage and family life. His argument for premarital chastity is particularly memorable, if quaint: marriage is a long business, he argues, and it would be a shame not to save certain delightful discoveries for the marriage bed instead of furtively rushing through them in the backseat of a car somewhere. He also makes a somewhat unconvincing but amusing argument that the ideal mother is a plump mother: more of her to love.

But after 27 years of marriage and six children, Capon divorced his first wife, Margaret. "As it has turned out," he wrote in The Romance of the Word, "there were a lot of departments in which I was not a success, not to mention several in which I was, and still am, a failure. … I dedicated a great deal of time and effort to my children's religious formation, only to find them now mostly uninterested and non-practicing." The failure of his first marriage and subsequent remarriage ended Capon's career as dean of a diocesan seminary and priest-in-charge of a mission church. His was not a life of "triumphant goodness or heroic efforts" but of "dumb luck and forgiveness." This only underscored his gratitude for God's grace and mercy; elsewhere he wrote:

Grace cannot prevail … until our lifelong certainty that someone is keeping score has run out of steam and collapsed.

"It has been an adventure," Mrs. Capon said of their marriage. She loved traveling with him for speaking engagements and book promotion, but she seemed equally enchanted with their quiet life on Long Island, where he wrote numerous books and articles on food and theology and served as a supply priest. Unlike Bed and Board and, very much more so, The Supper of the Lamb, now quite deservedly reprinted in a Modern Library Classics edition, none of Capon's later books (of which there are well over a dozen) sold very well. Finances were tight ("my decision to go freelance threatened constantly to become a license to starve," he once wrote.) There were some lean years, but with a laugh, Mrs. Capon recounted the time that her husband started a sermon in a church in East Hampton—well-known as a playground of the rich and famous—by setting fire to a $20 bill. "I have just defied your God," he said.

Until 2003, Father Capon served as an assisting priest at the Episcopal church fewer than 300 yards up the street where I grew up. I can remember learning to ride my bicycle in shaky circles in the parking lot of the historic (circa 1830) Baptist church that my father pastored, next to the parsonage where we lived. When I was ready to brave the sidewalk, I pedaled confidently until, passing Holy Trinity Episcopal, I'd invariably begin to totter. "Why do you always go wobbly when you pass the Episcopalians?" my father teased. "Do you find their theology wobbly?"

In truth, I was drawn to Episcopal worship before I had words to explain why. In my own church we sang songs that promised that if we turned our eyes upon Jesus, "the things of earth/will go strangely dim/in the light of his glory and grace." I was weak in the knees for a way of worshiping that did not pit the "things of earth" against the "glory and grace" of Christ, but was capable of seeing them—the humblest of elements—charged with such glory. This is what makes The Supper of the Lamb remarkable both as a work of theology and as a cookbook: "The world is no disposable ladder to heaven. Earth is not convenient; it is good; it is, by God's design, our lawful love," Capon wrote. For Capon, discussing the physics involved in the preparation of a perfectly smooth gravy—down to the details of what sort of whisk does the job best—was of a piece with celebrating the goodness of God who created it all for delight, who means to lift all the good things of this world to grace, to that

unimaginable Session

In which the Lion lifts

Himself Lamb Slain

And, Priest and Victim

Brings

The City

Home.

Robert Farrar Capon's writing is charged with an intense love for God and for all that God has made; it is deeply opinionated, utterly unique, and saturated with grace, reflecting the quirky appeal of the man himself, who, though now lifted to glory, leaves behind a warm invitation to taste and see that the Lord is indeed good.

Rachel Marie Stone is a frequent contributor to CT's Her.meneutics and author of Eat With Joy: Redeeming God's Gift of Food.