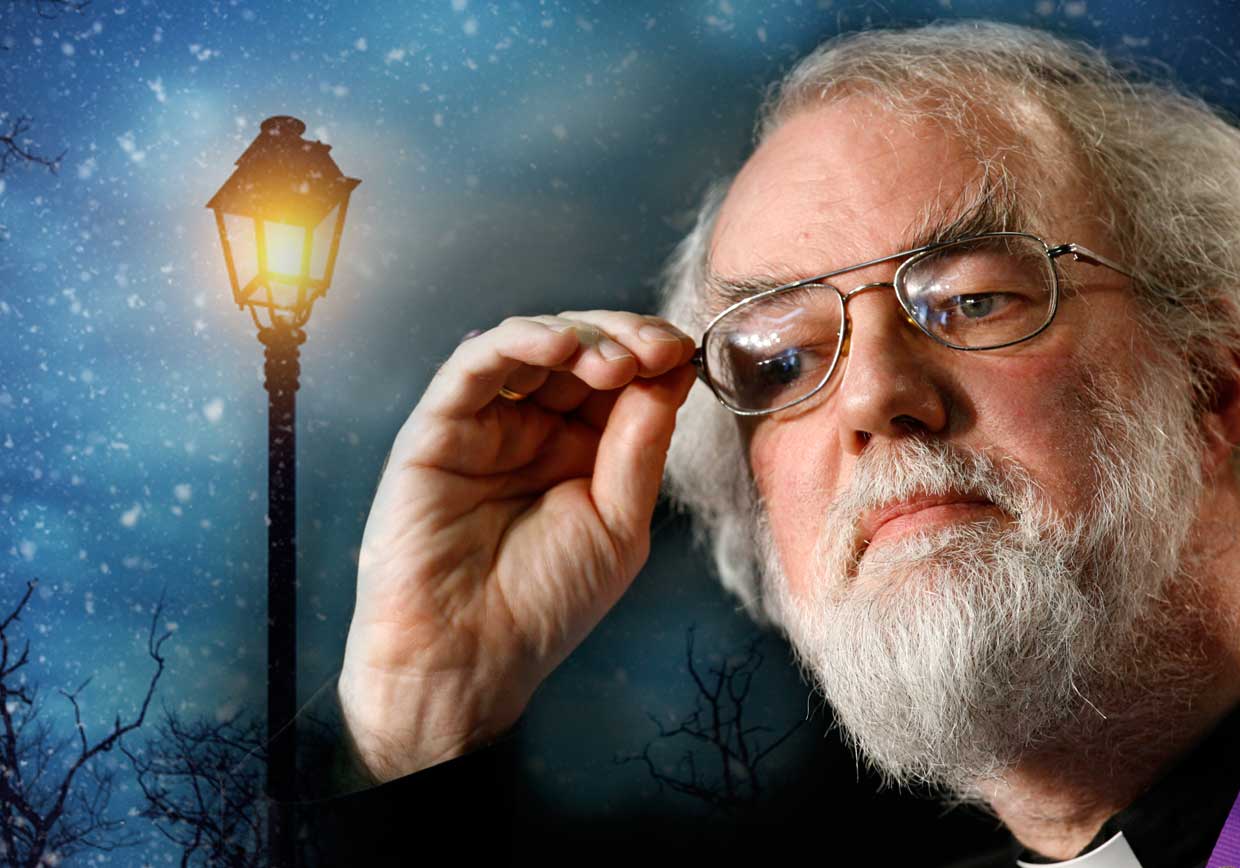

To many American readers, it probably doesn’t seem strange that a British Christian leader would write a book about C.S. Lewis’s Narnia. But as former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams himself notes, Lewis’s children’s stories have always been more popular in America than in Britain, especially among intellectual elites. Williams has published several significant volumes of theology and poetry, but earlier this year he released a relatively slim volume on how the Narnia books can reinvigorate readers’ understanding of the Christian message. While working as CT’s editorial resident, Melissa Steffan interviewed Williams as she reported a separate story on new interest in Lewis in the UK. (Meanwhile, the Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton College is today hosting a conference on why Lewis has had more influence in the U.S. than in his own country. Audio will be available shortly.)

Why write one more book on Lewis and Narnia?

The book began with three lectures in Canterbury while I was archbishop, trying to explain what I thought was going on in the Narnia books and what the main themes were. I wanted to emphasize two things.

First, the Narnia books were mostly designed to give you a feeling for what it’s like to be a Christian—not to make an argument or create an allegory, but to give a sense of what it’s like to respond in faith to Christ, what it’s like to be in a world where all your understanding is decisively shaped by that faith. Second, I take up a theme that comes up many times in the books, which is that we learn from our relationship with God to identify much more accurately how dishonest we are with ourselves about ourselves. Quite often you come back to the theme of stripping away the comforting story we tell about ourselves.

Did you grow up reading C.S. Lewis?

I’ve had a fascination with Lewis since my teens, (but) I didn’t grow up reading Narnia. I came rather late to Narnia, but I read quite a bit of Lewis as a teenager—Mere Christianity and The Great Divorce and some of the other books. As a schoolboy in the final year of high school, I read his book on Paradise Lost, which was very important for my English studies.

What was your introduction to the world of Narnia? What captivated you about it?

I suppose I read the Narnia books mostly as a student, and I enjoyed the wit of the books. Humor is very visible in them. I enjoyed the energy of the characterization.

And I just found myself very, very deeply moved by some passages, and I identify a lot with those moments of encounter—where you discover the truth about yourself in the face of God. Those are some of the most moving passages, because Lewis is particularly good at giving you a sense of joy in the presence of God.

What is it about Narnia, which can seem so obviously Christian to many readers, that appeals to non-Christian or secular audiences?

It’s not an easy question to answer. I think it’s partly that the narratives themselves have a great deal of force. You know, they’re very simple stories—I don’t mean simple in the sense of crude—but emotions are strong. They’re about loyalty and betrayal, victory and defeat. They have that sort of buzz; they just keep going and keep your attention.

They have at their heart something very mysterious, something that comes in alongside your ordinary human interactions and gives them an extra depth, an extra dimension, because Aslan is not a presence who’s visibly there all the time. Yet, there’s something or other breathing over your shoulder and making you think again, reminding you that you’re responsible to something bigger. I think that appeals to almost any intelligent or sensitive reader of any age.

Narnia is something that people do revisit. Some of the images stay with me. And though of course Lewis wrote them as children’s books—that’s what they are—children’s books, as we all know, are quite powerful tools for grown ups’ imaginations.

What do you think the artistry of Narnia tell us about Lewis?

Lewis is a brilliant storyteller; he’s not one of the world’s great novelists. But even so, what he does, he does wonderfully. He is always very good at depicting something about joy.

If you look at an extraordinary episode in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, where Lucy finds herself reading a story in a magical book, when she puts the book down she can’t remember the details of the story. She just knows that it’s the best thing she’s ever read, the most enriching and beautiful thing she’s ever encountered. As she’s talking to Aslan afterward she says, "Will you tell me that story again?" Aslan says, "One day I shall tell it to you forever." It’s that kind of moment where you realize that Lewis has got hold of something that very few writers do manage to crystallize, a sense of absolute immersion in the richness of the moment.

It comes across in The Screwtape Letters, which still read very well, when the one, old devil says to the younger devil that God’s great secret is that he’s a pleasure lover at heart. At the heart of it is joy. That’s Lewis all over.

A good deal of Lewis’s life, of course, was marked by enormous stress and great suffering. It’s not as if he had an unchallenged life. Some of the emotional force of his writing does come from his being a motherless child, looking back to that sort of magical world before the suffering broke in—and we all have a little bit of that in us.

But what he does with it then, instead of making it a cozy, backward-looking thing, he unites it to all of these great moral challenges, the challenge of facing up to yourself, the challenge of going on being faithful in prosaic ways day by day. It’s really only by doing the next thing—being faithful in small particulars—that you come to this joy. It’s not magic; it’s not nostalgia. It’s a very fine balance that he deals with remarkably.

So when he comes to write about his wife’s death in A Grief Observed, which is, for many people, the most extraordinary and challenging of all his books, it’s as if you know anything he says about joy or hope is hard won. It’s really something that’s come to him not by glib formulations or easy answers. He really has fought for it.

How do you think the Chronicles of Narnia differ from Lewis’s apologetic and academic work?

For me, and a great many others, Lewis’s apologetics are not necessarily the best place to start or finish. There is implicit in everything he wrote after about 1940 the strong sense of what it is to be human and the dangers of trying to run away from your humanity. There are people who are trying to stop being human and have no sense of belonging with other human beings or the world at all. There’s something about humanity being connected with humility. You accept where you are with humility, not passively or not giving way depression. But you accept that you are a bodily person living in a limited world and you get on with it there.

Your book spends a fair bit of space addressing critics who say Lewis is sexist or racist in his works. Why did you feel that was necessary?

It’s very easy to look at writers of another generation to say, "They should be just as enlightened as I am," with no sense that, had I been alive at that time, I might have had all the same attitudes. We have to see him in his context. Many of the clichés are really, really not true. There are many strong and independent women in his fiction. He’s not easily written off on that.

Sometimes, when we look at a writer of the past, what we see are the ways in which they are like other people of their period—they share the same attitudes about politics, about sex, about whatever. But what makes them great writers, what makes us read them still, is the ways in which they were different from other writers of the same era. They have some things in common with their contemporaries, but they have a lot more to them—and it’s that "a lot more" that we should be focusing on.

How have you seen Lewis’s legacy change in the UK over the past 50 years?

Obviously Lewis is still read by people for the apologetic and intellectual side, but for me—as well as a great many other people—that’s not necessarily the best place to start or finish. Here is somebody who knew the world of English literature—and indeed, European literature—as well as anybody in his generation, who himself had a really vigorous, creative imagination. I think more and more people are aware that you acquire faith not by a great exercise of the will, not by a great exercise of the intellect, but by something that happens to your imagination when it’s turned upside down.

What was the theological environment like at the time Lewis was writing? Why was he never really wildly popular among evangelicals and intellectuals in the UK at the time?

He was beginning to become more popular among evangelicals by the 1960s. In the late 1960s I can remember evangelical friends of mine who were reading him. But it may well be that we’ve come full circle, and people are more open to an imaginative approach. What’s curious is that in the ’30s and ’40s and ’50s, you do get quite a lot of imaginative approaches to Christianity, so it’s not as if there’s a shortage of people doing the imaginative work. Lewis’s originality was to do it with children’s fiction in a way nobody else was doing it.

Is Lewis enjoying a renaissance of interest and respect in the UK—among intellectuals and/or church leaders?

That would be accurate. We’ve gotten past the stage where people look down on Lewis. When I was studying theology, we certainly were not encouraged to read him, and there was a bit of embarrassment (about him). Now that’s gone. People are aware, first of all, that he’s a major literary scholar. His interpretations are still worth engaging with, simply as literary works. Secondly, there is something about his imaginative world which is very prophetic. For example, ecological spirituality is already kind of coming to the fore, and Lewis identified the problem over half a century ago.

There’s still a long way to go, to be honest. A good many self-consciously liberal Christians still think he’s some sort of reactionary. I mean, he’s a conservative, but he’s not a fundamentalist or a Religious Right person, and on some subjects, although he’s a man of his age when he writes about women or gay people, he’s much less offensive about them than some other writers of the era.

But he’s still certainly seen by some secular writers, like Philip Pullman, obviously, as "the great enemy." In a way, Pullman’s sequence of children’s novels is meant as a deliberate counterblast to Lewis, but that’s a backhanded tribute to Lewis’s stature and influence, to say he’s worth fighting.

Overall, how has Lewis’s work shaped Christianity in the United Kingdom?

I think the Narnia books have gone on as a steady background for a lot of people. In the last 40 or 50 years, the apologetic works have not been read so much. I don’t know many people who read The Problem of Pain or Miracles now, for example. I think it’s probably time to dust off the other books, like The Great Divorce, and it’s interesting that the science fiction books have regularly come back into print—and have mass sales still. He’s been there as a significant presence slightly offstage. A lot of people who have come to Christianity have picked up his books because they are immensely readable and enjoyable to read. The mainstream church is perhaps beginning to get over a little bit of embarrassment about him—that he’s too popular, or too conservative.

What I’d like to see is the church and the theological establishment saying, "Here is by any standard someone who is a serious intellectual, not just a journalist or a scholar, but an intellectual, somebody who thinks about the society we’re in." We need to reclaim him as such. It doesn’t mean we have to agree with everything that he says. It does mean that we try to take him seriously.