For the first year of the Global Gospel Project, CT focused on doctrines about the person of Jesus; in year two, we looked at God the Father. For year three of the project, we will look at doctrines related to the Holy Spirit. Recently, the Holy Spirit—specifically his role inspiring the expressive, charismatic spiritual gifts—has been at the center of debate among American Christians. But historically, the debate has focused on the Spirit's place in the Trinity. It is a leading factor in the longstanding division of the church between East and West.

The Eastern Orthodox Church and the Western churches (Catholic and Protestant) disagree over the Filioque, a Latin term in many ways as abstract as it sounds. Bradley Nassif, professor of theology at North Park University in Chicago, unravels the mystery of the dispute and explains the issues at stake.

Not all doctrines apply to everyday life, the Filioque being a good example. Even these, however, can end up impacting everyday relations between branches of the global church. If there is any practical application, then, it is to continue praying for the healing of division in the church. —The Editors

I love food, especially Middle Eastern cuisine. My Lebanese grandmother is to blame for that. When I was a boy, she would spend hours in the kitchen kneading dough, grinding lamb, boiling cabbage, mixing spices, rolling grape leaves, making baklava, and baking bread. Cooking was a way she showed her love.

The foods were elaborately prepared with time-tested techniques, each having a special Arabic name (too ornate to pronounce in English). Many dishes went back centuries, some to the days of Jesus. These treasures of the palate were artfully displayed on the kitchen table. Salads, desserts, side dishes, and main courses offered the best of Grandma's Mediterranean gems. I especially loved her hummus, a chickpea dip now popular in America.

Grandma died many years ago. For years I longed for her hummus. So this past summer, I took up cooking to try to remake some of her favorite dishes, including hummus. But to my dismay, I failed as I mixed the wrong ingredients and spices over and over again. "What am I doing wrong?" I asked. "Why can't I make hummus like Grandma did? Do I need to add more lemon? Is garlic necessary or optional? Must I use olive oil, or will canola oil do just as well? What's essential and what's not?" Eventually, I discovered the balance. Now my hummus is to die for—at least according to my family.

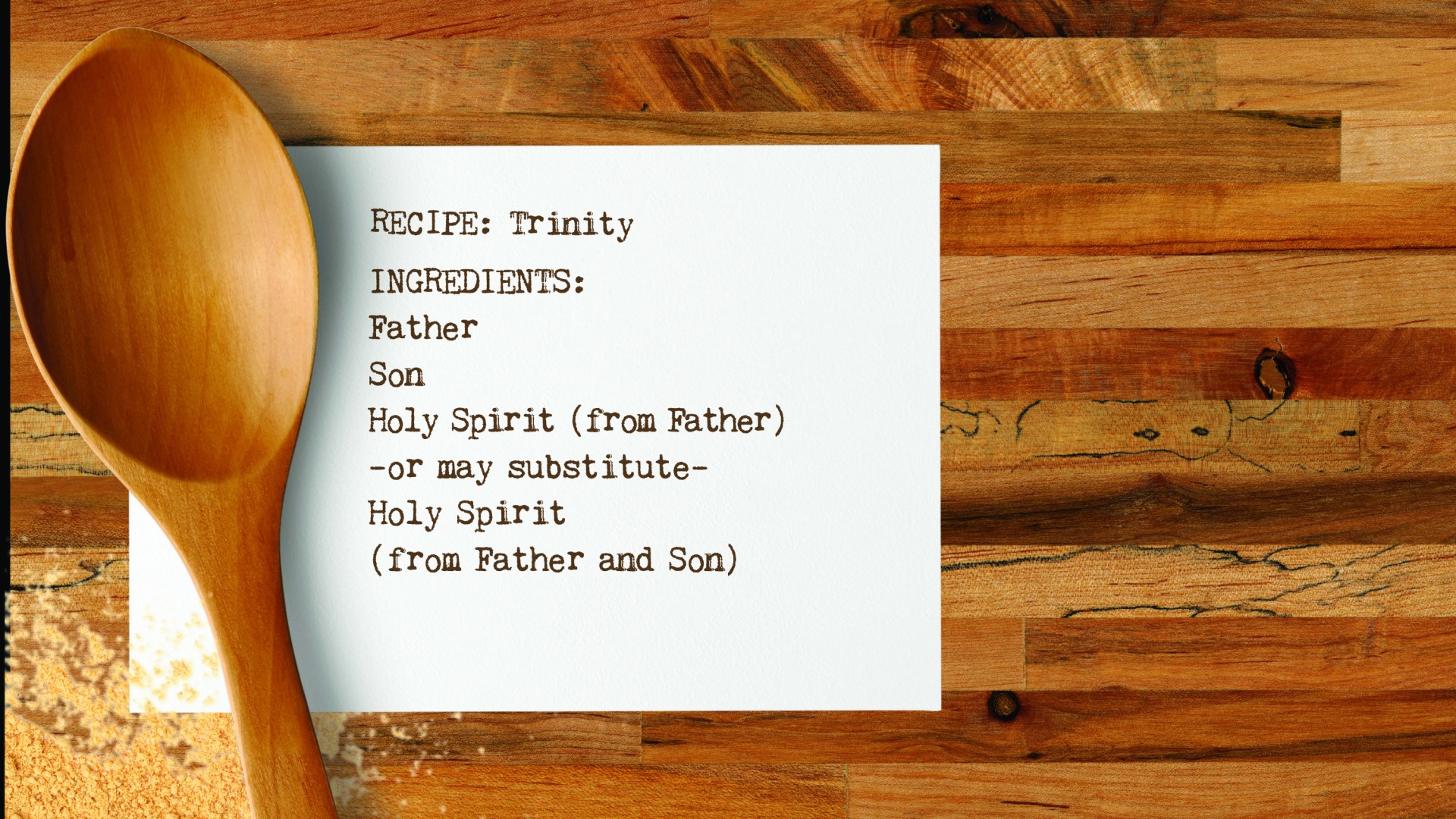

Similarly, Christians have a long tradition of enjoying a delicate combination of ingredients that compose a proper understanding of the Trinity. That beautifully balanced doctrine of the Trinity came in the fourth century, after church leaders reflected on how God exists as a unity of three equally divine and equally eternal Persons. The Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Spirit is God—three divine Persons sharing one divine nature. The doctrine was eventually summarized in the Nicene Creed.

The heresy the Nicene Creed stood against was Arianism. The heresy was named after Arius, a priest who believed that Jesus was not fully God but rather a created being through whom God the Father made the world. If Arius and his followers were right, enormous consequences would follow: The church would be wrong to worship Jesus as God. Salvation through Jesus would be impossible because only God can save—and Jesus would not have been fully God.

One Small Change

We won't quote the whole Nicene Creed here, but a passage from it forms one of the strongest dividing lines between Eastern and Western Christianity. It reads: "We believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the Giver of life, who proceeds from the Father, who with the Father and the Son is worshiped and glorified." When the creed was first written, the clause who proceeds from the Father was intended to safeguard the divinity of the Holy Spirit. By saying the Holy Spirit proceeds eternally from the Father, the creed maintained that the Spirit is fully God because he partakes of the Father's divinity.

Here is where the trouble began. The Christian West (later the Roman Catholic Church) added the Latin phrase Filioque— "and the Son"—to the above lines. Hence, the Spirit "proceeds from the Father and the Son." The Protestant Reformers of the 16th century, including Martin Luther and John Calvin, supported the Filioque.

Most evangelicals are barely aware of the issue. The Eastern Orthodox Church, however, has insisted on preserving the original wording of the Nicene Creed, keeping the Filioque out. For the Orthodox, the Filioque was never agreed upon by the whole church (East and West alike). And, more important, they believe it is simply wrong.

If truth be told, many people—Orthodox, Catholics, and Protestants alike—dismiss the dispute as obscure and inconsequential. But is it trivial? Or is it important to the way we conceive the Trinity? Does one small change affect the whole of Christian life and thought?

Issues at Stake

To understand what the global church has been debating for the past 1,500 years, let's go back to Grandma's hummus. What would happen if we added an extra spice to the original dish—say, jalapeño? Would this ruin the quality of the original dish? Those with a taste for classic cuisine would answer with an emphatic "Yes!" The recipe is no longer hummus.

But imagine that, instead of adding an ingredient, we simply rearranged the order in which the original ingredients were put together. Let's say we used the very same chickpeas, lemon, garlic, salt, and olive oil Grandma did, but just changed the order in which they went into the mixer. Rearranging them might actually help us remember all the original ingredients better, while ensuring the same delicious taste. That way, the hummus remains as true as ever, and Grandma and her ancestors stay happy.

That's how it was with the Filioque. The Eastern churches believed that adding "and the Son" to the Creed would change the very heart of the Trinity (a dish of a different kind). The West claimed there was no real change to the doctrine, just a rearrangement of the same ingredients that would ensure the original recipe.

What were the issues at stake in this controversy?

First, the debate centered on how the members of the Trinity related in eternity, not how they related in the world, such as when the Spirit was sent at Pentecost. Also, when asked how the Spirit's "procession" takes place, no one knew. It was a mystery found in the Bible and confessed by the church for centuries.

On the Orthodox side are two camps, one strict, the other moderate. Many strict thinkers regarded the Filioque as dangerous and heretical—a view held by people such as Photios (9th century), Mark of Ephesus (15th century), and Vladimir Lossky (20th century). They claim the Filioque confuses the eternal relations among the divine Persons and destroys the priority of the Father within the Trinity. If both the Father and the Son are sources of the Godhead, then the Spirit is subordinated to both, leading to a belief in two gods. Lossky has even blamed the Filioque for the Catholic emphasis on papal supremacy (a position today's more moderate Orthodox writers find farfetched).

Meanwhile, moderate Orthodox interpret the Western view on the Filioque to mean essentially the same thing as the Eastern view, thus preserving the divinity of the Spirit and the priority of the Father within the Godhead. Gregory of Sinai (13th century), for example, followed Maximos the Confessor (7th century) by refining the Western view to suggest that the Spirit eternally proceeds from the Father "through" the Son. Metropolitan Kallistos Ware sees it much the same way today. Regardless of the strict or moderate positions, Eastern theologians agree that there are two issues at stake in the Filioque debate: the truth of the doctrine itself, and unilaterally altering a creed that was accepted by an earlier ecumenical council.

In the West, Augustine first introduced the Filioque in his treatise On the Trinity (published in 419). There, he interpreted John 15:26 as referring to the Spirit, who "proceeds from both the Father and the Son." Following Augustine, the Council of Toledo (589) in Spain became the first Western council to support the Filioque. Rome accepted the doctrine in the 11th century. During subsequent negotiations with the East in the Council of Florence (1438–9), the West reaffirmed it. This confirmed how far apart the two traditions had grown.

The West argued that the Filioque was not, in fact, adding anything to the creed. Rather, it was a clarification intended to defend the faith against the Arian error that Jesus was less than divine. The Filioque rightly showed that the Spirit's procession from both the Father and the Son did not stray from the faith. As for the pope's right to alter the creed in this way, this was thought to be a privilege granted by Christ himself.

Does Scripture have anything to say about the Filioque? It does, though modern interpreters question whether the Bible explicitly teaches a theology of the Spirit's procession. The East would cite John 15:26 ("the Spirit of truth who proceeds from the Father," nasb), 3:16, and 14:26–28 as evidence that the Father alone is the origin of the Son and Spirit. Key texts supporting the Western position were Romans 8:9 and Galatians 4:6, where the term "Spirit of Christ" was thought to denote the Spirit's eternal origin from the Son.

In addition, the West often equated the eternal relations in the Trinity with temporal activity in this world, as when Jesus promised that he would send his disciples "another Paraclete" (advocate) when he departed this world (John 14:16, Douay-Rheims).

Taste for Yourself

So are the East's and West's Trinitarian views genuinely incompatible? Beginning in the eighth and ninth centuries, people certainly began to think that they were. As the centuries passed, power, authority, and heated conflict often ruled in the debate. Yet something more important was at stake: the fear that innovation had destroyed the purity of the faith and abandoned the teachings of the church fathers.

In recent years, theologians from both sides have gathered to reexamine the subject. The most notable attempt to heal the split is the North American Orthodox–Catholic Consultation and its document "The Filioque: A Church Dividing Issue? An Agreed Statement." One of the group's several conclusions reads as follows:

We are aware that the problem of the theology of the Filioque, and its use in the Creed, is not simply an issue between the Catholic and Orthodox communions. Many Protestant Churches, too, drawing on the theological legacy of the Medieval West, consider the term to represent an integral part of the orthodox Christian confession. Although dialogue among a number of these Churches and the Orthodox communion has already touched on the issue, any future resolution of the disagreement between East and West on the origin of the Spirit must involve all those communities that profess the Creed of 381 as a standard of faith.

And that takes us back to Grandma's hummus. Is the Filioque like an added ingredient? Three options are on the table: one from the West, two from the East. The West says the doctrine actually enhances the Nicene Creed by clarifying the inner life of the Trinity. But "strict" theologians in the East think it creates an imbalance among the members of the Trinity, destroys the Father as "sole source" of the Son and Spirit, and violates church unity. Orthodox "moderates" agree that church unity is violated, but think the Filioque can be true if we say that the Spirit proceeds from the Father "through the Son." Only if, in other words, the Son mediates—not causes—the Spirit's procession from the Father alone.

Readers will have to taste the theological hummus for themselves to see if East or West faithfully follows Grandma's original recipe.

Bradley Nassif is professor of biblical and theological studies at North Park University in Chicago.