Enjoy this excellent longer read from friend and artist Kyle Rohane, who parses the cultural challenges (and the power) of artistic response in worship. Read to the end, and engage in the comments. – Paul

Skriiiiiiit. I pushed my X-Acto knife through the black foam core. Dust particles spewed from its wake. A little pressure, and the piece snapped from the larger board. I tossed it into the growing pile of ten-inch square tablets. I may have been a seminary student, but I felt like a mad scientist. My "lab equipment" was piled around me: scissors, chalk, and stacks of paper.

"Five more to go," said David. Skriiiiiiit. I broke another piece off. We were inventors, crafting something new and unusual. But our creation wasn't the stack of tablets. Those were just the Bunsen burners that would ignite a spiritual reaction in our fellow students. Our invention was something grander. And our lab was Expression Night.

I felt lucky to attend a seminary that encouraged creativity and the practical application of spiritual principles we learned in class. Twice a week, we could attend Common Ground, a daytime chapel service celebrating our rich inheritance of ritual and tradition. But every few months, we'd schedule an Expression Night. It was student planned and student run—a sacred space, carved into our late-night study routine. On any given Expression Night you might find musicians improvising on their instruments, students writing furiously in journals, and even a language professor reciting biblical poetry in Hebrew.

This organic worship environment was the perfect opportunity for David and me to unleash our grand experiment. Skriiiiiiit. I cut off the last piece of foam core, and we gathered our materials, giddy with anticipation.

Uncomfortable Expressions

Before Expression Night began, David walked up in front of the small crowd of worshippers. He tapped the microphone twice and said, "Welcome to Expression Night.

"Tonight we have something new for you to try. Up to this point, we've provided opportunities to worship through music, writing, and even food. But now you have the option to worship through the creation of visual art." He studied faces in the audience. Were they eager, or did they seem a little perplexed?

"Off to the left, we've placed a stack of foam core tablets and chalk. There's also paper, scissors, glue—anything you might need to express yourself visually. You're free to create whatever you want on your little tablet, but try to use these tools to express your worship of God. It's not about creating a masterpiece; it's about listening to the Spirit's voice and responding to him through your art. When everyone has finished, we'll put the tablets together as a collage. It'll be a snapshot of God's movement in each of us tonight." David finished with a quick prayer, and the chapel came alive with the sound of praise music.

There were more worshippers than we had expected. I hurried to man my station, counting the tablets to make sure we had enough. A few people picked up chalk and started drawing—friends we'd asked beforehand to "salt the tip jar," so to speak. But as they finished their projects and moved on to other forms of worship, no one came to fill their places. I flicked my eyes around the room. There were a few people journaling in a corner. Two or three were sitting with their eyes closed, listening to the music. But most were standing at attention, comfortably singing with the praise music.

I sidled up to another friend who hadn't drawn anything yet. "Care to give it a shot?" I whispered. She smiled back and shook her head politely. "I'm no artist. It would look terrible." I reminded her that no one was going to judge her artistic ability, but she said, "Sorry, it's just too uncomfortable."

Too uncomfortable. Those words felt like a punch in the gut, and my enthusiasm was gasping for breath. I recalled an experience from a high school church retreat. I was born and raised on hymnals and pipe organs, a rock surrounded by a tumultuous sea of other students raising their hands in praise, dancing in the aisles, and shouting, "Halleluiah." I didn't just feel uncomfortable. I felt too uncomfortable.

The worship pastor called out, "Don't just stand there; raise your hands!" He was trying to unite everyone in praise, but I felt like I'd been singled out. I shrank back into my chair, mortified. The pastor shouted again, "Raise your hands even if you don't feel like it. Your posture will help change your attitude." But I didn't want to raise my hands. I crossed them in silent rebellion. I had been segregated, too uncomfortable to direct my attention to God.

Was that what our little experiment had done to the worshippers at Expression Night? Were we making people too uncomfortable to praise God in a new way?

A Pile of Sandals

Just then, two kids wandered over. I saw their dad standing with the other singers, eyes following his children. I handed the kids some chalk and asked if they wanted to draw something. Their faces lit up. They immediately dropped to their knees and started doodling. No inhibition. No anxiety. They just loved drawing.

Were they thinking about the complexities of their relationships with God? Probably not. But they were certainly worshipping. They were emulating their Creator in an act of creation, reveling in their extravagant mark-making. I thought to myself, At what point do we start fearing judgment so much that we forget how to create?

I had to admit, our goal with this experiment was to make people uncomfortable—just a little. When singing praise, it's easy to hide your voice behind that of others. Visual art is out in the open for all to see. And while songs end after a set number of choruses, visual art persists. We had hoped these factors would push people back toward a childlike vulnerability, in front of God and their brothers and sisters in Christ.

In Exodus 3, when Moses crept toward ground made holy by God's presence, why was he told to remove his sandals? Some say it was a gesture of respect, like removing your hat when entering a building. Others think it was more than that. His sandals would have been filthy, caked in dirt and pebbles. Removing them was a cleansing act that represented repentance before a holy God.

But what he exposed says just as much as what he removed. Callused as they probably were, Moses' feet were still left unprotected. The soft, fleshy pads of his feet met the harsh ground with each step he took toward the burning bush. Taking off his sandals was an act of reverence, but it was also an act of trust. He was rejecting self-preservation to rely on God. To approach the Lord, he first had to make himself vulnerable.

That's the balance we were trying to create at Expression Night. Like a game of paper football, we wanted to nudge worshippers just enough to face their anxieties without falling over the edge of fear's precipice. That's a fine line to tow, and it's different for every person. If I forced apprehensive people to draw, I'd be no better than the worship pastor who pushed me into my little rebellion. But would every one of them choose the comfort of singing praise music over the vulnerability of our little experiment?

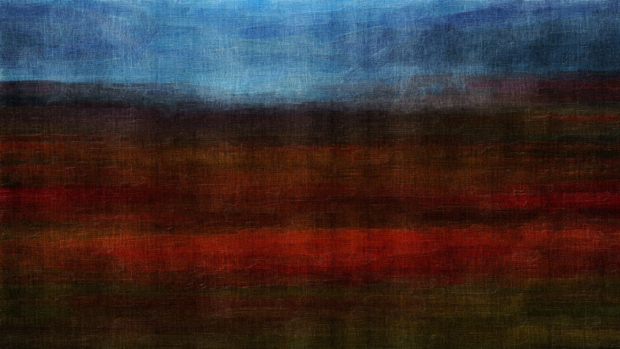

I'd like to think it was the kids who eventually attracted others to create their own drawings. Their uninhibited joy was infectious. First they ran off to pull their father back to join them. He chuckled and picked up a piece of chalk. Friends came over to see his "masterpiece" and tentatively tried it out for themselves. One person sketched a flower and surrounded it with a verse from Matthew—she was trusting God with her worries. Another drew himself hiking up a mountain, trusting God with his journey. A treasure chest. A tree. Abstract shapes and colors. Student after student crafted images and placed them next to each other.

Not everyone joined in—in truth, less than half. But I didn't begrudge those that didn't. The art project would have made them too uncomfortable to focus on God. But each new addition to our growing collage was another sandal cast off, an act of vulnerability in God's presence.

The next day, David connected the individual pieces and hung them in a seminary hall that was sure to get foot traffic. But the wall across from the piece sure looked bare. So we tried our experiment again at the next Expression Night. This time we let students draw on a single mural, to emphasize the communal nature of their worship. Those that contributed responded to each other's drawings, finishing images and filling in gaps. It was a beautiful reflection of worship in community.

In Fear of Christmas Carols

So should your church start passing out crayons during worship? Not necessarily. It takes a discerning eye to discover where a worshipper has become complacent, fixated on their comfort. But the question you should be asking isn't, Where is the line between "too uncomfortable" and "just uncomfortable enough"? The question is, Why should you push your worshippers at all? The answer—Because vulnerability breeds trust, in God and in each other.

A few years ago, I visited my wife's family to celebrate Christmas. She was my girlfriend at the time, but I was ready to propose. This trip was my chance to ask for her father's blessing. So when her sister sat at the piano and the rest of the family gathered to sing carols, I was fighting more than a little anxiety. As they sang one familiar hymn after another, I stood with my hands in my pockets and rocked back on my heels a few times. Finally, I took a deep breath and muttered a few verses, hoping my low voice would fly under the radar. My future mother-in-law put her hand on my arm, squeezed it, and gave me a little wink. She didn't care what my voice sounded like. She was just happy I'd dropped my inhibitions and joined the family song.

The good news about worship of any kind is that it's never something we're initiating. We aren't blazing lonely trails through untouched frontier. When we worship God, we're joining in the Son's eternal praise of the Father by the power of the Spirit. And we're adding our song to the chorus of those saints who came before us. So take off your sandals, wiggle your toes, and join the family of God in the circle of praise.

Kyle Rohane is Editor at LeaderTreks in Carol Stream, Illinois