Widespread acceptance in our culture of all forms of birth control, including abortion, makes it harder for the Christian to discern if, when, and how to incorporate such practices into one's own life, as well as what place personal convictions have in community and in public policy.

I suspect one of the greatest obstacles to constructive dialogue on the questions about birth control raised by the Hobby Lobby case is the imprecision of the terms being discussed. Perhaps, then, the first step toward finding agreement—or at least correctly identifying at the points on which we can agree to disagree—is to employ common definitions.

The debate around the Hobby Lobby case, birth control methods, and insurance coverage illuminates not only how deeply divided Christians are on these matters but also how ill-defined the central questions are. Questions of conscience are matters for all believers to respect in each other even amidst disagreement. If Christians cannot engage with each other with clarity, respect, and good faith on difficult questions, how will we do so with those outside the church?

In an effort to bring clarity to an otherwise muddled war of words, here are some of the questions central to this conversation. They're not as simple as we might assume.

How does the medical community define pregnancy?

At the heart of the debate is the question about whether or not certain birth control methods prevent pregnancy or terminate pregnancy. Part of the problem in answering even this basic question is that even the term pregnancy is not agreed upon universally and has undergone numerous changes, due less to scientific debates than semantic ones. While the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says pregnancy begins with implantation, most U. S. doctors surveyed say it begins when the sperm fertilizes the egg. Thus, the oft-repeated claim that debated birth control methods do "not disrupt an established pregnancy" might be misleading. Here's why: The phrase "established pregnancy" refers to post-implantation, which does not preclude the interruption of a newly formed life. However, marking pregnancy at implantation makes sense. Pregnant describes the woman's condition, but new human life can exist apart from pregnancy, as evidenced by countless fertilized eggs that don't implant—whether naturally or intentionally—and the thousands of frozen embryos known as "snowflake babies."

A more precise term than pregnancy, perhaps, is gestation, which, according to the National Institutes of Health, describes the period between conception (fertilization of the egg) and birth. It's noteworthy, though, that even the term conception is used in a variety of ways, sometimes meaning the moment of fertilization, other times to describe several stages of gestation. The different meanings of the terms conception and pregnancy obviously affect, in turn, the meaning of the word contraception.

What is birth control?

The NIH definition states, "Birth control, also known as contraception, is designed to prevent pregnancy." This would seem to go without saying, but the colloquial misuse of the phrase "birth control" as though it were a proper name muddies the waters. One is "using birth control" if one is using the method with the intention of preventing pregnancy. A woman who is receiving treatment solely to alleviate menstrual irregularities or other medical problems is not "using birth control" any more than a woman who undergoes a hysterectomy due to cancer is "using birth control." To advocate for "birth control" under the guise of other medicinal uses only sets the cause of birth control—and women—back by communicating obfuscation and perpetuating ignorance about female sexuality and reproductive health. If medications should be covered by insurance for off-label uses, that's an argument to be made intelligently on its own merits.

What is the difference between contraception and an abortifacient?

Again, this hinges on whether one considers abortion to be ending a pregnancy or ending a life. This distinction explains why methods that work between fertilization and implantation are considered by some to be abortifacient and by others to be contraceptive. In an article repeating a plea I made earlier at The Atlantic, the Daily Beast said of the birth control methods disputed in the Hobby Lobby case: "The contraceptives in question—Plan B, Ella, copper and hormonal IUDs—do not cause abortions as the plaintiffs maintain, because they are not being used to terminate established pregnancies… Even if morning-after pills prevented implantation, they would still work as intended: as safe contraception, not abortion pills." Yet, whether or not a method is considered contraceptive or abortifacient depends not only on how a mechanism works but also on what one considers the object of abortion: Is it the pregnancy that is aborted or a new life? To say that a method "prevents pregnancy" is not the same as saying it prevents fertilization. Abortion opponents are not opposed to ending pregnancy (after all, birth does that), but to ending a new life. Perhaps a term that all could agree on would be embryocidal, which speaks to any willful (rather than spontaneous) termination of an embryo, whether in the womb or in the laboratory.

Why do Hobby Lobby's owners believe that contraceptives are abortifacients?

They don't.

While countless bloggers and journalists have charged Hobby Lobby's owners with "believing contraceptives are abortifacients," such a statement is semantically absurd. Something that actually prevents pregnancy cannot end what it prevented in the first place. The question is whether certain methods may act as abortifacients rather than as contraceptives. (It's only semantics inasmuch as saying "I prefer coffee rather than tea" differs from saying "tea is coffee.") Of course, the absurdity of the semantic construction has the effect of rendering the position taken by Hobby Lobby as absurd. Yet, the concern that some birth control methods may be abortifacient rather than contraceptive is not a figment of anyone's imagination:

· The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists states, "Birth control pills contain hormones that prevent ovulation. These hormones also cause other changes in the body that help prevent pregnancy. The mucus in the cervix thickens, which makes it hard for sperm to enter the uterus. The lining of the uterus thins, making it less likely that a fertilized egg can attach to it" (emphasis added).

· The label for the popular birth control pill Yasmin (one of dozens of brands that use a combination of estrogen and progestin) states that "possible mechanisms may include cervical mucus changes that inhibit sperm penetration and the endometrial changes that reduce the likelihood of implantation." The so-called "mini-pill" which uses only progestin is labeled similarly.

· The NIH website says of hormonal contraceptives in general: "these pills can prevent ovulation; thicken cervical mucus, which helps block sperm from reaching the egg; or thin the lining of the uterus." Thinning of the uterine lining inhibits implantation of a fertilized egg. Another page at NIH states, "The pill also does not allow the lining of the womb to develop enough to receive and nurture a fertilized egg."

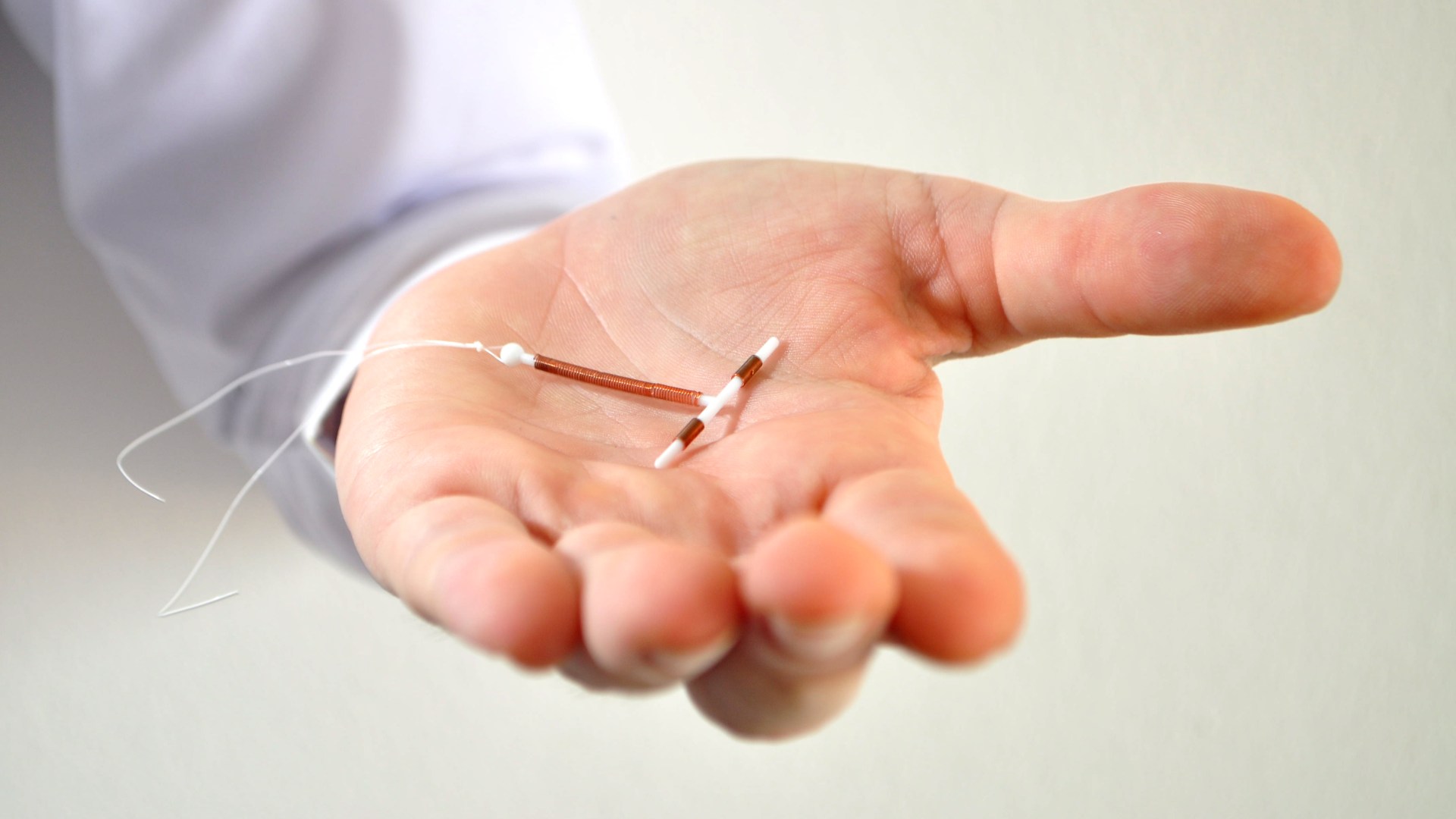

· The NIH states about the copper IUD: "If fertilization of the egg does occur, the physical presence of the device prevents the fertilized egg from implanting into the lining of the uterus."

Yet, despite these statements, abortion (and embryocide) opponents are repeatedly charged with lacking education and basing concerns about these medicines on "belief." Those who disagree with the drug labels and the NIH verbiage claim to simply be "satisfied with the science," offering personal speculations to explain the labelling such as "scientists, being scientists, will always answer 'yes' when you frame a question that way." Now, this may in fact be the case.

And it may be the case that new research (made public after the Hobby Lobby case began) will change the scientific consensus about these methods. But concerns about possible abortifacient mechanisms of some birth control methods are not based on belief but on scientific statements. It's a strange state of affairs when the people citing the medical community are said to basing their views on religious belief, and those basing their views on speculative theories claim they are the only ones with science on their side.

Given this data, I have to question Hobby Lobby's lack of consistency in not opposing all forms of hormonal birth control whose labels describe the same possible mechanisms. This is not to say, however, that a hypothetical that nags my conscience is a basis for which I'd offer a mandate for others, a point articulated recently in an article by my friend and fellow Christianity Today writer, Rachel Marie Stone. (The fact is that Hobby Lobby covers nearly all the birth control methods advocated in the article, which garnered high praise from some of the company's most vocal critics.)

Why does any of this still matter now that the Hobby Lobby case is closed?

It matters because the essential issue—which transcends Hobby Lobby, birth control, and even abortion——remains: the need to use common language in order not to talk past each other. When it comes down to it, most of this debate hasn't really been about birth control at all.

Karen Swallow Prior is professor of English at Liberty University and a regular writer for Her.meneutics.