Here's a provocative piece from PARSE friend Chris Ridgeway, who is tired of shoddy cultural exegesis where technology is concerned. Chris will offer the "Do" side of preaching on tech issues in a soon-to-publish piece. -Paul

The formula begins with a simple family illustration:

We sat down to dinner last week where Cindy had made chicken. While we are trying to get everyone to the table and the milk poured; I'm asking Katy, my 13-year-old, about her day. But she doesn't answer. She's got her phone out and her eyes are glued to that thing and she's tapping away and she's oblivious to our dinner preparations or anything I'm saying. My 8-year old? Same story!

Then, a revelation:

Then my phone buzzed and I pulled it out of my pocket to see a message from my associate pastor, and it struck me. There we were, all sitting around a table and good food that the Lord provided, and instead of seeing each other, we were each addicted to our tiny screens.

Then comes the indictment (in the form of a question):

Have you seen what technology is doing to us? Is technology separating us from each other? Is the very thing we say connects us, actually distancing us?

(With the quick caveat that tech is good for some Christian purposes):

Don't get me wrong: Facebook and iPhones they're amazing and useful technology that can be useful sometimes. Especially as a tool for spreading the gospel.

Then, the Scripture:

Have we forgotten that at the Tower of Babel, man's dependence on technological achievement had a consequence of separation?

Finally, the solution:

It's time to take a Sabbath from technology. Shut down your computer. Put that phone in a box. Stop living in a virtual world, and start to really relate to your family.

Each time I've heard this progression, I cringe. What's wrong? Not the recognition that our lives are looking different with new technology in the picture. That's self-evident. Or that we should think about the effects such developments and devices have in our families and churches. That's wise.

When technology starts getting a capital "T" and becomes the action hero of sentences ("Technology is …"), we've made a serious mistake.

But when technology starts getting a capital "T" and becomes the action hero of sentences ("Technology is …"), we've made a serious mistake. We're getting the cultural exegesis of technology all wrong, and I think that has real implications for pastoral practice.

Let's start with an apology for making pronouncements on who's wrong. It took years for me to wed my Microsoft consulting brain with the campus ministry years that followed. Back then, our students (and me) were some of the first in the country to get accounts on the thing then called TheFacebook, us peering over each other's shoulders to see what a "profile" was. Maybe it was the decade watching students living both with and without these recent technology innovations, but here's why I think some of our well-meaning cultural prophets are subtly misidentifying the culprit.

Don't start with "Technology is …"

Socrates recounts Egyptian mythology saying that the new technology of "external marks" (writing!) will "create forgetfulness in the learner's souls" (Phaedrus), and ever since it's been natural for us to levy some strong charges against the new-fangled invention of the day.

Screens are not stealing us, our phones are not making it impossible to have a conversation, and e-mail is not taking us away from people. Humans are the cause of technology.

But technology is not operating rogue. Screens are not stealing us, our phones are not making it impossible to have a conversation, and e-mail is not taking us away from people. These are not statements that deny the effects of technology in human lives (there are effects, and larger than we think), but phones aren't the cause, and putting down phones won't erase the effects. Humans are the cause of technology.

I don't mean only that Steve Jobs changed our lives with an iPhone or that it's likely some thirteen year old is, as we speak, hacking into the NSA. Gifted engineers and inventors are surely a real "cause," but there's a wider picture that involves you and me—humans as "users." As talkers, workers, jokers, and thinkers.

Technology is something that humans make and create around ourselves—whether or not we notice. It's a constant extension of how we learn, accomplish, associate, and create as people. It's so much from us that it becomes part of us. Technology is similar to language, symbols, social structures, art, and customs in this way. And we have a name for these things: culture. Technology is inseparable from human culture.

Fr. Walter Ong wrote, "The world that God created understandably troubles us today. … Some are inclined to blame our present woes on technology. Yet there are paradoxes here. Technology is artificial, but for a human being there is nothing more natural than to be artificial."

The trouble with both technology and culture is that they tend to be invisible except for the portion that is troubling us. A theology professor once told me that he was concerned about the arrival of technology—digital projectors—into liturgical worship. I wondered if he had noticed how overwhelmingly techy our liturgy already was—book-binding, moveable-type, and such. Like a hotbed of Wired magazine coverage for the 15th century.

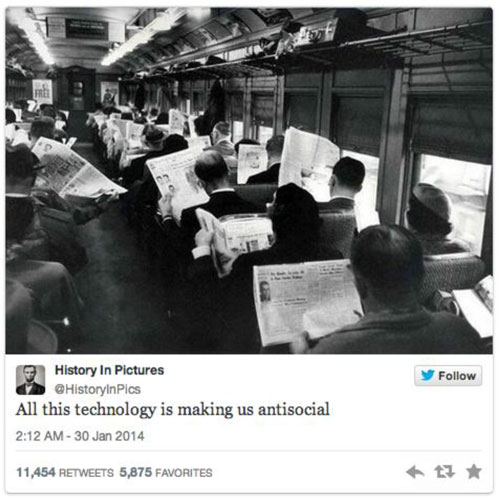

It's easy to worry about the screens our faces are buried in. With Facebook just since 2004 and iPhones just since 2007, it's easy to think we're noticing an unparalleled turning point in human history. Yet it's easiest to objectify the new things, while the things we're accustomed to become invisible to us. Did you see this recent re-tweeted meme?

Are the newspapers separating us from each other like never before?

Finding the real cause

Back in seminary, my friend Paul came upstairs to our apartment one day and declared that he had shut down his Facebook account. "Deleted it!" he said. "I'm done." "Why?" I asked. "I don't like how I'm not getting things done. I'm supposed to be writing a New Testament paper, but I'm checking Facebook instead. It's a complete distraction from studying. From life!"

I think his concern over his study habits were real stuff. Biblical exegesis papers never looked particularly fun when entertainment beckoned, and the Greek text was looking like, well, Greek.

Yet several weeks later, I issued a group dinner invitation via Facebook, and voila—he RSVPed. "I switched it back on," he admitted. "It turned out that I just watched TV instead. And I was missing social invitations!"

"We have met the enemy … and he is us!" is the famous quote from Pogo, and it doesn't seem to get old in the way it aptly describes the human condition. Mark Zuckerberg didn't invent the tension between work and play, relationship and isolation. For my friend, Facebook may have mediated these things but it wasn't the cause. He acted like every other human I know. The cause was himself. We simply can't isolate technology effects from our own selves.

The cure for ourselves

When technology is treated as external to us—or even the enemy—the pastoral solution becomes easy: avoid it, control it, delete it. Put it in a basket and stop turning it on.

So our appeal might simply be this: don't preach about technology. Preach about people living in a technological world.

But our need for relational connection, our tendency to distract instead of feel, or our desire to be productive—these are inseverably human traits. They are as chock full of sin and grace as they always have been. At the family dinner table, we're not staring at screens. We're staring at human nature.

So our appeal might simply be this: don't preach about technology. Preach about people living in a technological world. Don't preach about technology as Godzilla storming towards us with destroyed culture and relationships in its wake. Preach about technology as a new mirror on human nature—as beautiful and fallen as it's always been.

And you'll probably want to answer that text from your associate pastor.

Chris Ridgeway is on the leadership team of Great Commission Ministries directing communications. He blogs at www.theodigital.com.