See the introduction to this series on religious themes pop culture explored in 2014, and yesterday’s post on memory and justice.

The word “evil” is almost hard to say today—not because it's verboten, but because it conjures up over-the-top images from campy horror movies, or moustache-twirling villains who are eeeeeevil.

But actual evil? As in wickedness, depravity, corruption? We don't use the word evil much to mean those things, because most of us as modern and sensible folk aren't sure what it is. There are a few things we're willing to call evil, like child molestation or genocide, harm done to innocents that is unimaginable to most of us. But when we do something wrong, we tend to call it a “mistake,” or blame it on people's ignorance.

Generally, to us, evil can't be some kind of separate agent that transcends beings—haunting, broaching their borders, and possessing them at will. It can only be something that comes from within individual people (and, sometimes, bad institutions). For the past couple centuries, we've suspected that people do “evil” things because their selves were corrupted before they had the chance to mature into reasonable, rational, properly socialized adults.

Unlike what our ancestors a millennium ago might have believed in our place, we have to believe that Hitler wasn’t evil because he was possessed by evil; he was evil because he was a frustrated artist, mentally unstable, an unchecked megalomaniac. A school shooting isn’t the result of demons, not to most people, anyhow—it’s because someone’s insides got twisted because they weren’t able to respond to adversities that life threw in their path. And maybe they were schizophrenic, too, and it went undiagnosed. That doesn’t make it less tragic, but it does reframe the conversation.

In 2014, evil continued to take us by surprise. What can account for the beheadings of journalists or children? What about the deaths of unarmed young people, or of cops at point-blank range? Death threats against women? Stories unearthed of sexual violence? Lies and deceit? People dying from drug overdoses? Anger and hatred we witness on almost a daily basis? We see so much of it, but we don't seem to become immune to it. It shocks and disturbs us.

And yet—where does it come from? We're frustrated with evil, and part of the reason is that as a society, we're just not sure of its origin. We don't think about demons and the devil all that much, except as generalities to explain what we see around us.

HBO

HBOThat question of the origin of evil—and of whether it comes from individual people, or whether it's separate from us—seems to pop up over and over again in popular culture. And it seems like 2014 had more than its fair share of shows and movies that were obsessed with what happens when we enlightened moderns encounter something inexplicable, something like the powers that our pre-modern ancestors took for granted. And they never let us off with easy answers.

To name but a few: True Detective, once again, was a tale mostly of grappling with evil. Rust Cohle may talk like a nihilist for most of the show, and he dismisses with irritation the religious people he encounters. But he's the archetypal tortured soul, a man who thinks he may need to be a sort of scapegoat for humanity. Once he starts having visions—and especially when he encounters true evil (linked to extreme violence against women and children)—his tune starts to change. “There's a weight that's got fishhooks in your soul,” someone tells him, and later he says that the “world needs bad men to keep other bad men from the door.”

True Detective is loaded with imagery drawn directly from much older stories about hell and the devil, and, by the end, Cohle must directly confront a mystical evil power. Evil, it seems, comes both from within and from without. In the season finale, which many audiences hated, after weeks recuperating in a hospital from his brush with pure evil, Rust tells his partner: “I been up in that room looking out those windows every night here just thinking, it’s just one story. The oldest.” “What’s that?” Marty asks.

Rust replies, “Light versus dark.” And when Marty replies that it looks like the dark has a lot more territory, Rust thinks about it a while, then says, “well, once there was only dark. You ask me, the light's winning.”

BBC America

BBC AmericaAnother show that took evil seriously was the British show Broadchurch, which was remade into Gracepoint this fall. If True Detective gives us an evil that transcends humanity but can alight upon it at will, Broadchurch gives us an evil embedded deeply into every human heart. Nobody gets off the hook. Each of us—even those who don't and would never kill or molest a child—is born with evil and inescapably broken. (I wrote about systemic evil in Broadchurch and True Detective earlier this year.)

Then there are movies like Wild (here's my review), which features a protagonist trying, in a sense, to exorcise evil or make penance for past actions by going on a sort of pilgrimage, a time-honored spiritual discipline employed by many of the world's major religions (including Judaism, Islam, and Christianity). The pilgrim begins his or her journey as an act of devotion as well as a sort of purification rite, experiencing hardship and pushing body and mind far beyond the usual bounds in order to cleanse the soul. And that's exactly what happens to Cheryl Strayed on her journey up the Pacific Coast to the (aptly named) Bridge of the Gods; while she might not talk about evil or wickedness, she believes that what's broken inside her is her problem alone. She wasn't possessed; she made choices to get to where she was, and she can make choices to heal, as well.

ABC

ABCOr there is the show Scandal (which I've written about), which continues to be wildly popular, in which the choices a person makes certainly go a long way towards defining his or her character—but not just those choices. There's also the matter of why the choices were made; the show moves back and forth between the idea that the wrong thing may be okay if done for the right reason. If you kill someone, but you do it to save the world, you might still get to wear the “white hat.” In Scandal, evil isn't something “out there,” judging you—it's something you define.

Warner Bros / Paramount Pictures

Warner Bros / Paramount PicturesThe film Prisoners, which released late in 2013 and was reviewed for us by Brett McCracken, does something similar, looking at evil from an often explicitly religious viewpoint, but permitting characters to descend into evil through their actions and choices. In the case of the protagonist of Prisoners, his own brushes with evil turn him into someone willing to perpetrate it; the result is so disturbing I haven't been able to shake it since I saw the film, and shows us a wickedness that comes not from beyond, but directly from human agency.

I hardly need to tell you that the problem of evil is as old as time, and that it is deeply religious, with every age and religion or system of belief from ancient religions to Star Wars offering their own answers. We moderns feel comforted by the idea that evil is something we create or choose through our own actions—and therefore it's something we can choose not to embrace, something we can control or destroy on our own.

Certainly, Christian theology has this idea embedded in it; in a Christian anthropology of man, we are given the freedom to choose life or death, to do good or evil.

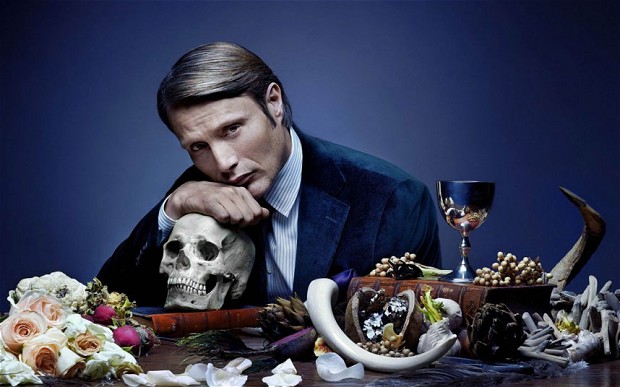

NBC

NBCBut that's not the end of the story, because Christian theology also proposes that evil can come from beyond us, in ways that often seem senseless and random. Evil, to Christians, is the twisted good. It is perversion of what is beautiful—something the visually-stunning show Hannibal, which is rife with religious themes and also profoundly disturbing, captures perfectly. Evil isn't exactly the opposite of good, so much as its horrifying mirror image.

But because we expect that we can control evil, we're surprised and frustrated when we can't. That's something our ancestors understood much better. They worked hard to keep the forces of evil away with prayers or spells or charms, believing that they might be penetrated by evil against their own will.

It seems to me that the reality of evil isn't so much an either/or as a both/and. Evil comes from beyond us. It also comes from within.

Paramount Vantage

Paramount VantageOne of the greatest (if not the greatest) living American writers is Cormac McCarthy, an avowed atheist who nonetheless has a darkly religious view of evil in every one of his books. (If Christian theology says that evil is the absence of the good, McCarthy tends to believe that good is merely the absence of evil.) In No Country for Old Men, he writes evil as a living, breathing character, played by Javier Bardem in the film, who roams about the countryside wreaking havoc at will.

In his novel All the Pretty Horses, McCarthy puts this explanation for evil in the mouth of a Mexican prisoner, speaking to a young American cowboy:

Americans have ideas that are not so practical. They think that there are good things and bad things. They are very superstitious, you know . . . It is the superstition of a godless people . . . There can be in a man some evil. But we dont think it is his own evil. Where did he get it? How did he come to claim it? No. Evil is a true thing in Mexico. It goes about on its own legs. Maybe some day it will come to visit you. Maybe it already has.

And of course, the genre that most consistently grapples with evil (and makes a ton of money at the box office) is horror film. In an interview with us earlier this year, Scott Derrickson—director of Deliver Us From Evil, Sinister, and The Exorcism of Emily Rose, and also a vocal Christian—said this:

I think there's a real mystery to the inexplicable irrationality of true evil—both human and spiritual. I think that the more I work in the genre, the more I see it and the more I learn about the mysteries that can be worked in the world and how it's at work in my own life and within me. It's one of the reasons I do what I do. I am obsessed with it.

It’s interesting, even heartening, to see that the stories we’re telling ourselves seem to be coming up with both sides of the answer to the question of evil. In a world that's reluctant to even talk about evil, we're lucky to have so many artist working in pop culture that make us think about its nature—and we'd be wise to take them seriously.

You can find me on Twitter at @alissamarie.