“What if I could put him in front of you, the man that ruined your life? If I could guarantee that you’d get away with it . . . would you kill him?”

So goes the voiceover (and, essentially, the film’s premise) in the trailer for Predestination, a stirring new movie about time travel—and how one’s actions in the past can have huge ramifications for the future.

Ben King / Signature Entertainment

Ben King / Signature EntertainmentIt’s a cinematic conceit I’ve always enjoyed pondering, going back to watching 1960’s The Time Machine as a boy, and continuing through such films as Back to the Future, Groundhog Day, the Terminator films, Looper, and, most recently, Interstellar. (Oh, and one you may have never heard of, the obscure 2004 indie gem Primer.)

Done well, it’s a great genre. It forces you to think hard and use your imagination.

But done “well” does not necessarily mean you’ll completely get it. Such movies always require a suspension of disbelief. And sometimes, a suspension of logic. Predestination certainly requires the former, and, after just one viewing, possibly the latter. I’m not entirely sure, though, because about two-thirds of the way through, I quit taking notes altogether and simply wrote two words on my legal pad:

MIND BLOWN.

To paraphrase the voiceover in the trailer, let me put it this way:

“What if I wrote down every single scene and word of dialogue from this film? What if I could guarantee you could even read the script . . . would you get it?”

Likely not. This is a film that probably requires repeated viewings to totally connect the dots.

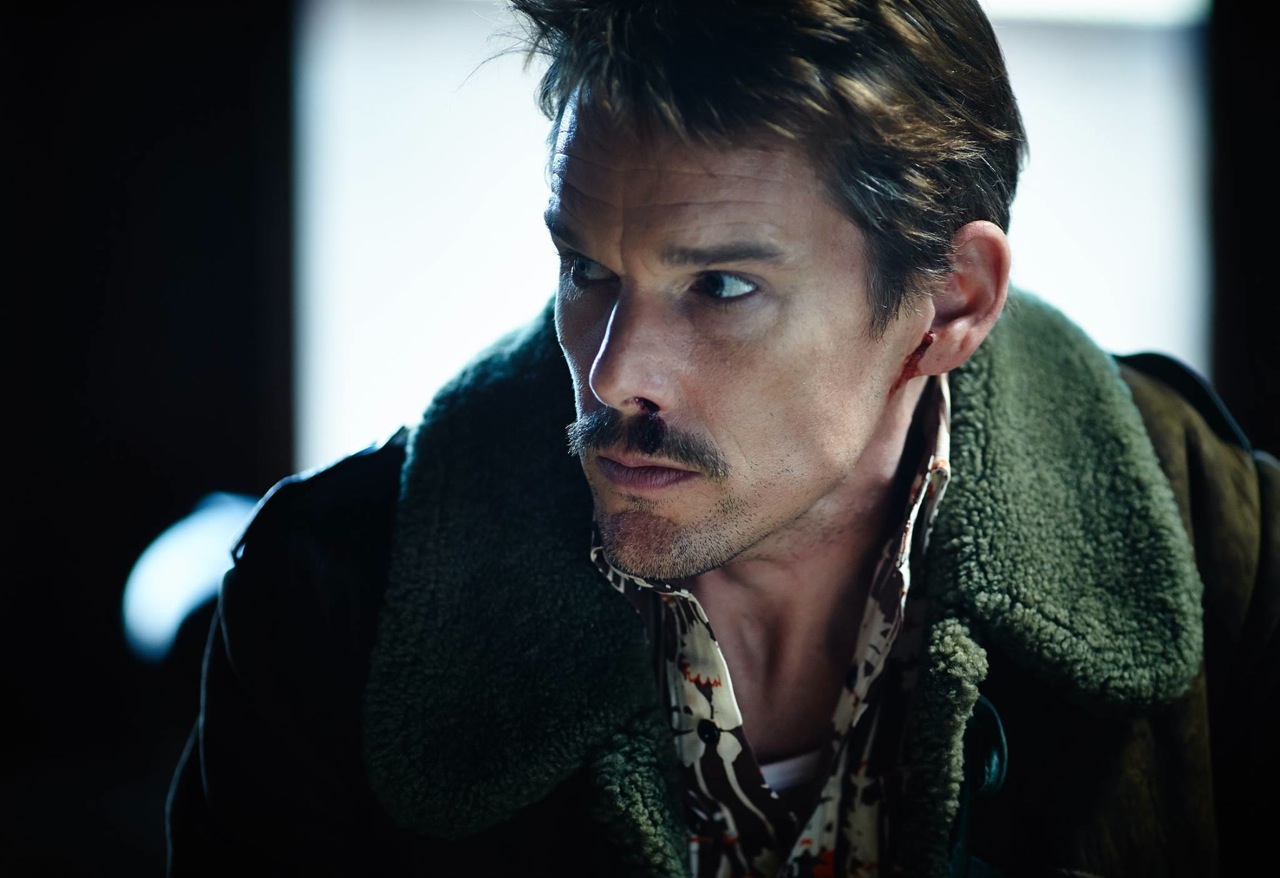

When Ethan Hawke, who plays one of the two lead characters in Predestination, first read the script by brothers Michael and Peter Spierig (who also co-directed the film), he said, “What the [bleep] did I just read?”

Ben King / Signature Entertainment

Ben King / Signature EntertainmentBut that didn’t deter Hawke, who often embraces unconventional indie fare, from signing on. And it didn’t deter Sarah Snook, a relatively unknown Australian actress, from accepting the film’s co-lead role. And it shouldn’t deter sci-fi fans from watching it, either.

I’m convinced that subsequent careful viewings will reveal more insight and make more sense, including some of those moments where you slap your palm against your forehead and say, “D’oh! Of course! Now I see how that adds up.” In a Sixth Sense sort of way.

Here’s the set-up.

Hawke’s character, never given a name, is simply The Bartender. He’s also The Temporal Agent. He poses as the former, but his real job is the latter—essentially a cop who travels into the past to prevent crimes before they happen. (Yes, it feels a lot like Minority Report on some levels, but on a tighter budget and without the special effects. And yes, it feels like a Philip K. Dick rip-off, but it’s really based on an obscure 1959 short story by Robert A. Heinlein called “—All You Zombies—”. And yes, “—All You Zombies—” is punctuated like that. I know, right?)

Ben King / Signature Entertainment

Ben King / Signature EntertainmentSnook’s character is more difficult to describe. It’s 1970 when he/she (keep reading; I’ll explain) walks into The Bartender’s joint and says, “I’m going to tell you the best story you’ve ever heard.” The Bartender pulls up a chair and listens . . . and indeed, it’s an incredible tale. Snook’s character, who appears to be a young man when he begins telling the story, reveals that he was born a girl—named Jane—in 1945, and then promptly abandoned on the doorstep of an orphanage.

Jane grew into a rough-and-tumble tomboy and an academic whiz kid, especially in math and science. She had no friends and was constantly teased. As an older teen, she was recruited by the Space Corps for potential future space travel. But she was disqualified when doctors discovered something odd about her physiology. (More on that in a bit.)

Soon after, Jane meets an older man (we never see his face, one of the film’s many hmm-what-might-this-mean moments), falls in love, and gets pregnant. The older man then abandons Jane, leaving her emotionally devastated, but determined to give her baby the childhood Jane never had. But those plans are dashed when her baby is kidnapped from the hospital nursery, never to be seen again.

Ben King / Signature Entertainment

Ben King / Signature EntertainmentDuring Jane’s C-section delivery, doctors discover that she has both male and female reproductive organs. The latter were destroyed during delivery, so Jane has a hysterectomy and, after further procedures and testosterone treatments, becomes a man and changes her name to John, who later earns a living writing “true confessions” for magazines, using the moniker of “The Unmarried Mother.”

And that’s who walks into the bar, ready to unload this incredible yarn.

Whew.

All of that just sets the stage for the wild ride that ensues. After hearing the story, The Bartender/Temporal Agent tells John that he can take him back in time to kill the man who abandoned Jane, using the words that opened this review:

“What if I could put him in front of you, the man that ruined your life? If I could guarantee that you’d get away with it . . . would you kill him?”

John jumps at the chance. But I won’t go into detail about what happens thereon, except to say that the third act involves a lot of time travel, forward and backward, in this sequence (I think)—1945, 1963, 1985, 1963, 1970, 1992, 1964, 1945, 1964, and I’ve probably missed a few. And you likely won’t be able to keep up. I sure didn’t.

But that’s hardly a deterrent. The film is so well made, so tautly acted, so nerve-wracking and tense, you won’t be able to turn away. Your brain might give up somewhere around 1970 (or was it 1992?), but your brain will also want so desperately to figure it out that you’ll long to watch it again, to see what else you can glean on subsequent viewings.

As for the title, Predestination, one could argue that it should be Predestination?—with the question mark, because it doesn’t seem to draw a definitive conclusion. Nor should it, but it certainly is asking the right questions: Are events in our lives truly foreordained? Or do we have free will to choose? Or a bit of both? As is true in most time-travel films, this movie implies that “predestined” events can indeed be altered, and that crimes can be prevented before they are committed. Predestination explores these things in more of a show than tell manner, but a few juicy lines of dialogue prime the pump. For example:

Ben King / Signature Entertainment

Ben King / Signature Entertainment— Early on, The Bartender/Temporal Agent says, “Time catches up with us all, even those in our line of work. God, Jesus, that sounds arrogant. I guess you could say we were born into this job.” I doubt if he was addressing God and/or Jesus here, but it's interesting that the Creator of time and space gets a shout-out in this context.

— In a nod to The Fall, which “predestined” us all to sin, John says, “Sometimes, I think this world deserves the s— storm that it gets.” The Bartender replies, “Let’s face it, nobody’s innocent.”

— In a nod to the meaning of existence, John asks The Bartender what people want out of life. The Bartender says, “Love.” John: “F— love. A purpose.” Bartender: “You don’t have that?” John: “I’m working on it.” Bartender: “Why can’t love be a purpose?”

— And finally, in a nod to free will, John asks The Bartender if he has a choice to do a certain action during one of the time travels. Bartender: “Of course, you always have a choice.” John: “But sometimes don’t you think that things are just inevitable?” Bartender: “Yes, the thought has crossed my mind.”

It will cross yours too, this collision of free will vs. predestination. You’ll be thinking about it throughout the film, when the credits roll, and long afterward.

And, like me, you’ll probably feel inclined to watch it again.

Do I have a choice? Or is it my destiny?

Caveat Spectator

Predestination is rated R for violence, some sexuality, nudity and language. There’s not much violence, but one scene is pretty gory. The sexuality and nudity are minimal, and non-gratuitous. There’s a fair bit of bad language, typical for an R-rated film. Take the rating seriously, not just for its content, but even for its ideas and complexity. It’s great discussion fodder for adults and older teens, especially when considering the issues of free will vs. predestination. And, for people of faith, asking how God plays a role in both—and how he might play a role in a world that really did include the possibility of time travel.

Mark Moring is a CT Editor at Large and a writer at Grizzard Communications in Atlanta.