The nation’s highest court kicks off the New Year with an unlikely case, brought by the pastor of a 30-member church that meets in a senior center in Arizona.

Clyde Reed, pastor of Good News Presbyterian Church, is fighting the town of Gilbert, a Phoenix suburb named in 2013 as one of America’s 10 most friendly cities for conservatives.

Good News, a member of the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church, has used temporary signs to announce services since it began 14 years ago. In 2005, Gilbert began enforcing a sign code restricting the size, location, number, and duration of signs advertising events. Penalties for breaking the code include fines and jail time for repeated violations.

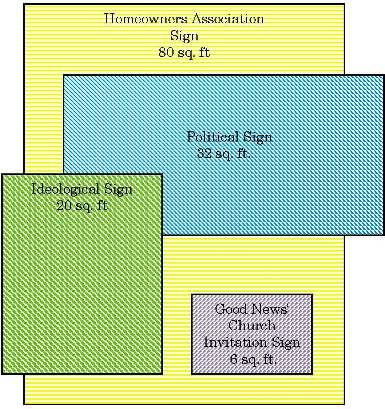

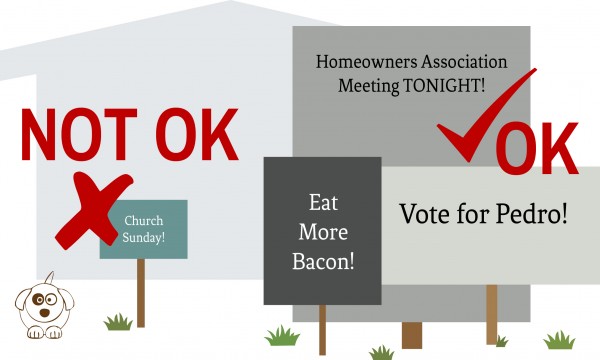

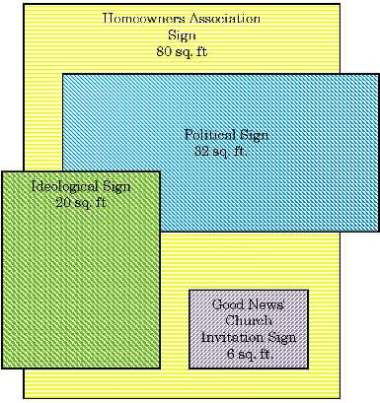

The restrictions don’t apply to political, ideological, or homeowners association signs, which can be larger and displayed longer. “The government shouldn’t be able to pick and choose speech favorites,” said David Cortman, vice president of litigation for Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), which represents Reed.

The case, which will be argued January 12, could clarify the “distinction between content-based and content-neutral restrictions . . . [which is] one of the most important rules of First Amendment law,” said UCLA’s Eugene Volokh, Notre Dame’s Richard Garnett, and other law professors in an amicus brief supporting Reed.

Even in the digital age, road signs remain important, said Thomas Berg, a law professor at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota, who filed a brief arguing that Gilbert is infringing on the constitutional right to assemble. “Even a general Google search for a church doesn’t reach the same audience as a sign reaching people who are just driving through.”

Gilbert attorney Michael Hamblin says the sign code is intended to make things easier for churches and nonprofits, allowing them to place temporary signs without first waiting for a permit.

“The ADF wants religious groups to be allowed to post free, permanent advertisements throughout an entire city area without any regulation or restriction,” he said. He noted Reed’s case had lost twice in the federal district court in Phoenix, as well as twice in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco.

Few cases make it through the costly and time-intensive litigation process to arrive before the Supreme Court. This makes Reed’s case unusual. But the fact that the plaintiff represents such a small religious group is not, said Eric Rassbach, deputy general counsel of the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty. Larger churches and religious organizations often have political clout that smaller ones do not.

“It’s not an accident that it’s [smaller] groups running afoul of the political system,” Rassbach said. “In this situation, there’s no political cost to just shutting down the signs. That’s when you want the First Amendment to come in and protect the little guy.”