Alissa's note: this interview was originally published in July 2014, but the film is available starting today on VOD, so I'm republishing the interview. You can find out more here.

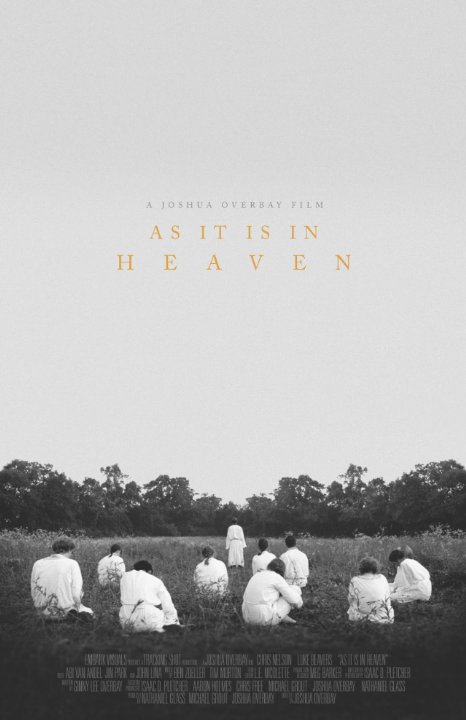

A week ago, I saw As It Is In Heaven, a low-budget, Kickstarter-funded, gracefully-shot independent feature film about a doomsday cult somewhere in the American South.

I was pleased with what I saw. Others were, too: the film earned positive reviews at RogerEbert.com, The Hollywood Reporter, and The New York Times, where it was named a Critics' Pick.

Most of us have never been the leader of a doomsday cult, I presume (I haven't), and we generally don't hear their stories, instead believing that such a person is a megalomaniac, mentally unstable, or just plain evil. David, the leader at the center of this film, is certainly some—if not all—of those things. But there's something more to him: a deep desire to live the right life, to find meaning in the world and even, after a fashion, to serve God as best he can. David is not a good leader, but he is a true believer.

Not only is the story suspenseful and engaging, but it acts like a mirror: these characters have characteristics and wants and motivations that find their reflection in us. And so while you may never have thought about joining a doomsday cult, you might discover that you see yourself up there on the screen.

After all, who among us—even the most faithful believers—hasn't wondered, while praying, if anyone was listening?

As It Is In Heaven was directed by Joshua Overbay, who cowrote the script with his wife, Ginny Lee Overbay, and shot the film near where he was living in Kentucky, where he was teaching at Asbury College (he's since relocated to Baton Rouge). He was kind enough to answer some questions about low-budget filmmaking, tackling his own ego and doubts, complex characters, the problem with "Christian" filmmaking (and how to make it better), and more.

How did this movie get made? What was the budget, and how'd it get funded? How did you cast it? You wrote it with your wife—how did that happen?

This was born out of another project falling through. My production partner, Isaac Pletcher, and I were working on a horror film for over two years; the script was locked, some cast and crew were in place, but there was no money. We had a lot of momentum going into the summer of 2011, but then we had a couple failed investor pitches and suddenly all progress grinded to a halt. We were trying to raise $1 million and it was simply out of our league. (I reference this in my article about being a microbudget filmmaker on IndieWire.)

A baptism in the film AS IT IS IN HEAVEN, about a religious sect approaching the end of the world. Photo credit: IN HEAVEN MOVIE, LLC. http://asitisinheaventhemovie.com.

A baptism in the film AS IT IS IN HEAVEN, about a religious sect approaching the end of the world. Photo credit: IN HEAVEN MOVIE, LLC. http://asitisinheaventhemovie.com.It took us a few months to come to terms with the fact that this project was not going to happen, and that's when I decided to reconsider my approach to making movies. I had been too concerned with establishing myself as a marketable director and less concerned about making something genuinely meaningful. I had neglected my responsibility as an artist: to tell the truth, to be honest, and to consider the impact my film might have on its audience.

Instead, it was about "breaking in" and "getting my name out there." For As It Is in Heaven, I decided to look within, to be more personal, and to use my film as an opportunity to confess something I had hidden: my doubts.

As a first-time director, I knew the project would need to be made on the cheap. I knew I would have to depend heavily on the students and grads of Asbury University to serve as cast, crew, and Kickstarter promoters. Three of the producers/executive producers, in fact, were former students of mine: Michael Grout, Aaron Holmes (who also served as the camera operator), and Nathaniel Glass (who was the 1st Assistant Director and Post-Production Supervisor).

I knew we would have to crowdfund it—and we did via Kickstarter. I knew I would have to recruit my film school buddies. I knew I would have to bring in my production partner in a few months before shooting to pave the way for the production. I knew we would have to get really lucky and find "undiscovered" talent in the Kentucky region who would be willing to act for free. And beyond this, my wife and I knew we had to write something incredible that could be shot on essentially one location.

With our shared background in Pentecostalism, and my fascination with cult leaders, we landed on setting our story in the world of a small doomsday cult. My interest was to simply use the setting as an external mechanism to communicate my experience with unquestioned faith. And beyond this, it was my attempt to deconstruct my own faith.

Some have said that our portrait of David (the film's protagonist) is dangerously sympathetic. But I wasn't thinking about this when we wrote it. I was simply trying to show how one could go move from certainty to uncertainty, despite one's sincerity and desperation. I was simply trying to make David feel what I was feeling when I started writing the script.

Chris Nelson as David in the film AS IT IS IN HEAVEN, about a religious sect approaching the end of the world. Photo credit: IN HEAVEN MOVIE, LLC. http://asitisinheaventhemovie.com.

Chris Nelson as David in the film AS IT IS IN HEAVEN, about a religious sect approaching the end of the world. Photo credit: IN HEAVEN MOVIE, LLC. http://asitisinheaventhemovie.com.The film is complex; in a key scene that involves an altercation between two important characters, I found myself thinking that this scene could be read in several different ways, depending on what movie it was in. What makes this movie good, I think, is that it refuses to "tell" you how you should feel about anyone. How did you approach this sort of character development?

Thank you for saying that. It's exactly what I was hoping people would experience.

All the depictions of ceremony and religious experience were pulled directly from my past. Though the aesthetic is more formal, I wanted to approach the content as a documentarian might. Based on my experience with religious fanaticism, and my research into cults, I felt it was my responsibility to humanize the cult members. To chip away at the idea of "craziness," and ultimately replace it with "desperation." "Craziness" gives viewers the freedom to distance themselves from the characters and turn them into "others."

I did everything in my power to make viewers uncomfortable with the normality and sincerity of the characters, in hopes of creating an empathetic bond between with the characters and the viewers. For some, this may cause pity; for others, hatred. It honestly depends on the individual viewer. I did my best to find the humanity in each character, especially David.

What was the role of place in your filmmaking which (I think) was set in Kentucky, near where you were living when you shot the film?

I live in Baton Rouge currently, but, at the time, was in Lexington, Kentucky. It's a gorgeous place to shoot and the community was very supportive. We got crazy lucky and actually saw no rain during the 17-18 day shoot. In addition, our producer, Michael Grout, found a perfect location for us: a remote farmhouse located in Nicholasville, Kentucky. We were able to rent it for two weeks before principal photography began. The Production Design team, led by Meg Barker, repainted the entire house. It was an insane amount of work, but it provided complete control of the color palette and allowed us to maintain a consistent aesthetic throughout the film.

Kentucky is a beautiful place to film, so it was easy for us to take advantage of this visually. Despite this, we never wanted the location of the farmhouse to be referenced in the film. We wanted the geographical setting to remain ambiguous, so that viewers wouldn't be able to associate their religion with a certain region of the country.

A lot of people assume it's in the South, but if you notice, there are no accents in the film. In addition, I wanted to reduce the entire screen world to the remote farmhouse, in hopes of making it feel like a microcosm. That's why we never leave the house after minute 15 of the film. I wanted it to feel like the safety of the entire world hinged on what happened at this remote farm.

Chris Nelson as David in the film AS IT IS IN HEAVEN, about a religious sect approaching the end of the world. Photo credit: IN HEAVEN MOVIE, LLC. http://asitisinheaventhemovie.com.

Chris Nelson as David in the film AS IT IS IN HEAVEN, about a religious sect approaching the end of the world. Photo credit: IN HEAVEN MOVIE, LLC. http://asitisinheaventhemovie.com.Obviously, religion plays a key role in this story—what we might call religious extremism. And yet, I detect a note of sympathy in the film that reminds me of the book Consulting the Faithful by Richard Mouw, in which he talks about what "sophisticated" Christian intellectuals can learn from the more "popular" branches of our faith. Where do you place this cult? And what did you learn from them as you wrote them into being?

I wrote from my experience, and it was my conscious goal to bring the "Christianity" of the group as close to the Evangelical Pentecostalism I encountered. The only thing that separates them from more mainstream versions of Christianity is their special knowledge about the date of the rapture.

However, their experience of feeling separate, special, and uniquely chosen is not unlike what I've witnessed in many charismatic and Pentecostal congregations. It's also similar to what I've experienced in the many Christian communities I've been a part of, especially the evangelical colleges I went to/taught at. That's how I see this group: desperate for meaning, a sense of community, and purpose.

There are lots of other groups like this, just in more socially acceptable manifestations: sports fanaticism, nationalism, tribalism, political allegiances, religious fundamentalism, etc. Our thirst for belonging is universal, and there's nothing wrong with this, nor is there anything we can do to remove it.

Things just get screwy when we become more committed to the satisfaction of this desire than to the pursuit of truth. To seek the truth, we must accept the fact that it may not cohere with our belief system, and must be willing to adjust our beliefs to match it. Otherwise, self-delusion and destruction will occur.

Four things I've seen recently seemed to resonate with your film as I watched: the shots and framing of David Lowery's Ain't Them Bodies Saints, the complex megalomaniac leader played by Philip Seymour Hoffman in P.T. Anderson's The Master, the place-based sensibility of Jeff Nichols (especially in Shotgun Stories), and, maybe oddly, the cult sub-plot line in Orphan Black. But I'm interested in whom you had in mind: to whom do you look as inspirations in your filmmaking?

Wow! What an honor to be mentioned among such incredible filmmakers. Seriously. I'm a huge fan of Jeff Nichols, and Paul Thomas Anderson is an idol. I've also met David Lowery and he's a wonderfully kind and intelligent man. (Editor's note: we interviewed Lowery last year.)

I find my influences to be difficult to track. I've been inspired by many writers and thinkers. Some philosophers, a few theologians, a couple of novelists, and now . . . lots of scientists. Filmmakers, however, have made the largest impact on my work. The filmmakers from the late 60's and 70's continue to inspire me. Their work remains compelling and relevant, because of their commitment to telling the truth regardless of the consequences.

Luke Beavers as Eamon in the film AS IT IS IN HEAVEN, about a religious sect approaching the end of the world. Photo credit: IN HEAVEN MOVIE, LLC. http://asitisinheaventhemovie.com.

Luke Beavers as Eamon in the film AS IT IS IN HEAVEN, about a religious sect approaching the end of the world. Photo credit: IN HEAVEN MOVIE, LLC. http://asitisinheaventhemovie.com.Lars Von Trier's Breaking the Waves is a masterpiece that every atheist and Christian should see. Scorsese constantly inspires me to make bolder movies. Roger Ebert's review of Bringing Out the Dead changed the way I thought about making films.

For As It Is in Heaven, in particular, I have to mention Bergman and Tarkovsky. Both were major discoveries for me in film school. After watching Stalker, I became obsessed with Tarkovsky, mostly because I couldn't fully grasp what he was doing, but also because there was also something ineffable in his work: a spirit in it I couldn't pinpoint. As a committed Orthodox Christian, he approached filmmaking much like an iconographer would an icon: prayerfully and with deep respect for the materials. I believe it's what gave infused his work with such transcendence.

I was also influenced by Bergman's "Faith trilogy," primarily Winter Light. His portrait of a priest on the brink of losing his faith is, in my opinion, the most beautiful and authentic depiction of Christian spirituality in cinema. The voice of the priest becomes Bergman's voice, and I find this vulnerable style of filmmaking beautiful. Faith, in Bergman's hands, becomes a mechanism for examining the human condition, which (in my opinion) is what cinema was built for.

Regarding our aesthetic choices, there were a few specific films that we referenced as we shot the movie. By "we," I'm referring to Isaac Pletcher, who produced and served as the cinematographer of the film. He and I have worked together since film school. We talked frequently about The Tree of Life, There Will Be Blood, Apocalypse Now, "Winter Light, The White Ribbon, and The Apostle.

What advice would you give to a young filmmaker today who wants to make "Christian" movies?

After teaching at an evangelical college for four years, two things have become very clear to me about potential Christian filmmakers: First, most of them hate faith-based films. Yes, "hate" is a strong word, but I think it's true to their emotions. And second, they have big questions, lots of wonder, and many doubts.

And yet, most of them feel that there's no space in their work for their wonder or their doubts.

I think this is because they've only witnessed two types of expression of faith in film: the "heavy-handed sermon" kind and the "promotion of family values" kind. In neither space is there true freedom to explore spiritual/existential questions. The former disallows the exploration of the darker side of our condition, while the later prohibits a more overt examination of faith. But there's a long, more obscure, tradition of filmmaking which creates a space for genuine spiritual reflection and exploration.

I would encourage young Christian filmmakers to watch the work of Bergman, Scorsese, Tarkovsky, Malick, Dreyer, and others. Then, take a long look within. Be painfully honest in your self-examination. And from this space, begin your work.

I believe there are many filmmakers out there who want to discuss their faith, but are afraid of being perceived as "faith-based" propagandistic filmmakers. And I would like to challenge them to resist this temptation. Be honest and be prophetic: afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted.

Check out the film and see where it's playing on the movie's website.