David Whitlow / AFFIRM Films/Provident Films

David Whitlow / AFFIRM Films/Provident FilmsAlex and Stephen Kendrick, darlings of the Christian film industry, are back in theaters today with War Room, their fifth film overall and their first since 2011’s Courageous. War Room is produced by Provident, but it’s being distributed by TriStar, which shows that they’ve come far—and that commercial studios are certainly willing to court Christian viewers.

A few years ago, a studio executive told me that the primary place in which the typical Christian film suffers, compared to its mainstream peers, is in the writing. Many Christian productions are willing to hire experienced, professional directors; even when they’re shot by self-taught cinematographers, the result is usually at least adequate. Christian productions now attract familiar stars: Robert Duvall in Seven Days in Utopia; Sean Astin in Mom’s Night Out; Cybill Shepard in Do You Believe?

But when it comes to screenplay writing, the genre seems stuck in a rut. It’s more committed to heavy-handed providential plotting than imaginative explorations of character or setting.

War Room follows the increasingly dreary pattern familiar to anyone who has seen more than a handful of Christian films. Karen Abercrombie and Priscilla Shirer are easy to like as a spiritually mature senior on the one hand and a beleaguered housewife on the other whom the older woman teaches to pray. T. C. Stallings plays a flatter character: Tony, the not-yet philandering but not exactly faithful husband to Shirer’s Elizabeth. The women deliver lines like “Devil, you just got your butt kicked!” and “Go back to hell where you belong, and leave my family alone!” with the requisite earnestness to make viewers believe that they believe.

But believe what exactly? That prayer is good?

Because that seems to be the film’s thesis, and it is so anxious to underline and demonstrate that thesis that it jettisons any bit of characterization or plot incident that isn’t immediately and directly tied to Clara’s or Elizabeth’s prayer life.

Tangential question: are addresses to Satan prayers? I found it odd that in a movie about the centrality and necessity of prayer, the characters are shown contending with Satan more often than attending to God. This seems to be a subtle way in which the film—and maybe the strain of Evangelicalism it is made for—flirts with turning prayer into a work.

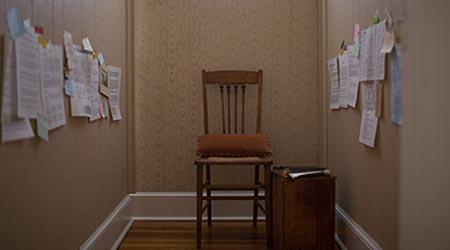

Elizabeth’s prayers themselves are implied through montages and post-it notes, and Miss Clara’s instructions seem to have more to do with manipulating the external environment than the content or execution of prayer. The film’s one specific piece of advice—you should have a space dedicated exclusively to prayer in your home—is certainly not bad. But it’s also one of several places in which the film is more exclusively directed towards the affluent viewer who has that space to spare than it perhaps realizes.

Avoiding Controversy By Being Innocuous

David Whitlow / AFFIRM Films/Provident Films

David Whitlow / AFFIRM Films/Provident FilmsCollege English professors teach their freshmen a common axiom: if you pick a thesis for your argument that nobody could, or does, disagree with, it’s a bad thesis for a paper.

That goes for films, too. In this case, the thesis is that "prayer changes things." It just does. End of story.

Christian Films frequently avoid controversy by being innocuous. They smooth the edges and elide the elements of our faith that we struggle with or argue about. This is a problem.

Being inspirational or uplifting is fine. But to sustain the hazy good feelings wrought by Christian art means more than promoting bromides about how our God is able. It means demonstrating those truths by embedding them in fully realized and developed narratives. And when those narratives aren’t fully developed, when characters aren’t carefully and lovingly drawn as real people, they can wind up backfiring subtly for the film.

This is precisely where War Room, like so many Christian films, stumbles. The characters and situation are so thinly drawn that even those of us who believe in the film’s ultimate message have a hard time with the package wrapped around it. Tony, Clara, and Elizabeth don’t come across as real people, but as stock figures in a sermon set in in some indeterminate Christianville. By standing in for everyone, they come across as having no real, personal identity of their own. Because the setting is meant to be anywhere, it comes across as unlike any place that is real.

That vague setting is especially evident in how the film depicts social class, along with the financial perils that Tony’s dishonesty supposedly create. Do the Jordans and Miss Clara belong to the same social class? Miss Clara apparently inherited her home from her husband who fought in the war; she is selling it to a pastor who doesn’t look as though he is wealthy or representing a megachurch. Is this an instance in which the spiritual wisdom and happiness of the middle class is meant to teach a lesson to the wealthy? Are the Jordans wealthy? Early on they certainly are. In one of the film’s first scenes, Tony slams Elizabeth for giving five thousand dollars from the couple’s discretionary account to her sister. It’s worth noting here that Tony doesn’t object because this is a significant portion of the family income. Rather, he says that he makes “four times as much” as Elizabeth, and so should have final say in how even discretionary income is distributed. What’s more, he argues that his sister-in-law is responsible for her own precarious financial position because she married a no-good, lazy, bum. That Tony is African-American is meant to inoculate the film, I guess, from playing on class stereotypes, anything that would suggest that all recipients of charity are capable individuals who simply lack the work ethic of the financially successful.

Class Mysteries

But Elizabeth is a part-time real estate agent and housewife, so that “four times” is a puzzling piece of lazy writing, allowing the Kendricks to convey the power dynamics within the family without requiring them to research or imagine specific details about their characters’ lives. Is Elizabeth a power realtor making a killing in commercial leases who only happens to be selling Miss Clara’s house?

Given the amount of time she spends with Miss Clara drinking lukewarm coffee and soaking up pearls of wisdom, it’s hard to see how she has time to stage, show, or sell a lot of other houses. Later in the film, she mentions asking her boss if she can pick up a few more properties, so she is definitely represented as an agent and not an independent realtor.

David Whitlow / AFFIRM Films/Provident Films

David Whitlow / AFFIRM Films/Provident FilmsLet’s say that Elizabeth makes $40,000 a year, just below the average for a full-time real-estate agent. That would mean Tony is taking home a healthy $160,000 from his job selling pharmaceuticals. (If any of my readers are in sales for a living and that sounds high or low, please drop me a line.)

When Tony is fired for “padding” his accounts, he has to give back the company car and worries openly that the Jordans “might” lose their home. Yet after an indeterminate period of unemployment—the film relies heavily on at least four montages to suggest the passage of time—he accepts a job at the community recreation center for “half” what his other job paid. (If any of my readers organize jump rope contests for primary school kids and get paid $80,000 for their efforts, please drop me a line and an application.) A chastened Tony now wants to help out his in-laws, but economizing means the couple can only afford to make a car payment for the never-seen poor relations.

After just a few weeks (possibly months) of unemployment, Tony is able to land a job that requires no specialized education or training, no references, no experience, and still pays enough to leave a couple hundred left over to help out extended family. Unemployment is either calamitous or no big deal, an actual blessing in disguise. Elizabeth is either entirely dependent on Tony or makes enough money working part time to support the family indefinitely. What’s going on here?

A Sermon Illustration, Not a Movie

My hunch is that the Kendricks aren’t really interested in how prayer saves Tony (or in what it saves him from), only asserting that it does. War Room is a sermon illustration, not a movie, and it needs only include details that underline the parable, not those that ground it in the real world.

The finances are not the only place where the script is indifferent to devilish details, only the most visible. How exactly does Tony pad his accounts or keep back a portion of the drugs for his personal stash? I have never worked at a hospital, but even I have seen enough episodes of ER to know that nobody just walks into a medical facility’s pharmacy and logs in how many drugs he is dropping off.

That Tony’s boss is reluctant to file charges struck me as feasible, that he handles the theft of product and Tony’s de facto robbing of clients as a strictly internal matter does not. Given the company’s liability vulnerability, there is no realistic reason Tony’s boss doesn’t turn him in to the police, even before Tony confesses to his secret stash.

David Whitlow / AFFIRM Films/Provident Films

David Whitlow / AFFIRM Films/Provident FilmsBut the script wants to reward Tony for stepping out in faith, and director Alex Kendrick himself takes on the role of CEO/expository preacher, explaining more for our benefit than Tony’s why he isn’t turning him in—it’s a parable of earned grace, a reward for doing the right thing, see?

I also have a hunch that the script’s greater comfort in discussing the importance of prayer than in showing the mechanics of making a living is indicative of a broader dis-ease in American evangelicalism, rather than a personal blind spot in the artist’s imaginative vision. With issues of class and race minimalized—Tony experiences no visible, overt racism, even from the executive who wants to turn him into the police—the film ends up spiritualizing all social problems, seeing their root in Satanic opposition and, hence, defeated primarily through prayer.

There may be seeds of truth in this theodicy, but in War Room, the enemy only works through direct, psychological attacks on individuals, never through the racist, patriarchal, oligarchical infrastructures of this world. I’ve long argued that Americans’ suspicion of Marxism and socialism extends to evangelicals’ neglect of the Social Justice Tradition (to borrow a term from Renovare).

Elizabeth does say at one point that it is hard to submit to the pre-repentant Tony, but the film nowhere grapples with this kind of complementarianism, or even suggests that Elizabeth doesn’t share some or most of the blame for Tony’s moral failings, since she neglected her wifely duty to pray for him. All of the couple's problems are results of bad (and unnecessary) choices on the husband’s part—none of them from ever being in seemingly untenable positions caused by unjust actions of other people.

Easy Fixes

Neither are any of the couple’s problems anything that can’t be solved in a single step, through repentance alone.

David Whitlow / AFFIRM Films/Provident Films

David Whitlow / AFFIRM Films/Provident FilmsAs mentioned earlier, Tony’s theft is forgiven and after a short period of chastening, he is rewarded with another, better (albeit lower-paying) job. Tony confesses to a flirtation, but he has fortunately stopped short of adultery, so there are no illegitimate children, sexually transmitted diseases, or emotionally enmeshed and damaged mistresses to negotiate once he has turned over a new leaf and started washing Elizabeth’s feet.

I was always taught in my Christian Education that there are acts of sin and there are habits and bonds of sin. (In an early scene, Tony lustfully ogles a woman while sitting in a church pew.) God can and does forgive both, but He does not always magically shield us from the consequences of the bad choices previously made. If you want to see what a lifetime of pursuing Mammon does to people who suddenly try to economize, check out The Queen of Versailles. If you want to see how hard to slip are the habits of promiscuity for those who have repented, check out Thanks for Sharing. If you want to see how ingrained are the patriarchal assertions of privilege within most evangelical communities, read the comment thread in just about any article on Her.meneutics.

Tony’s transformation is so complete, his break with the habits of sin so absolute, that one sees him not so much as a man emboldened and encouraged through prayer but as the prize given to Elizabeth when she pulls the prayer lever.

Another Way

My experience watching War Room was not helped by the fact that I have seen two veritable masterpieces in the last year about well-rounded characters brought to their wit’s end by the pressures of unemployment.

In Two Days, One Night (now streaming on Netflix in the United States), Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne detail a weekend in the life of Sandra (Marion Cotillard), a recently laid-off worker who has forty-eight hours to convince her eighteen co-workers to forego bonuses so that she can keep her job. In that film, not only the protagonists, but each of the co-workers she appeals to, is painted with more depth and nuance than any of the characters in War Room.

In another film, Clay Hassler’s Homeless, a teen tries to cobble together enough money for the security deposit on an apartment before his dad is paroled from prison. Shot on a budget of only $20,000 and using volunteer actors from the Winston-Salem community, Hassler’s film masterfully portrays how both bad choices and infrastructural roadblocks combine to make the crawl away from poverty painfully slow and precariously uncertain.

My prayer as we head into the fall and winter film season is that audiences who may not be fully satisfied with the Kendricks’ film seek out and find Homeless. War Room doesn’t have a bad message, but in nearly every area, and especially in its writing, Homeless is the better film.

Kenneth R. Morefield (@kenmorefield) is an Associate Professor of English at Campbell University. He is the editor of Faith and Spirituality in Masters of World Cinema, Volumes I, II, & III, and the founder of 1More Film Blog.