On October 25th, a bizarre year in Guatemalan politics took another unexpected twist with the overwhelming victory of avowed evangelical Jimmy Morales.

The dark horse, under-funded candidate had come from behind in a field of 14 aspirants to lead in the first round, and demolished former first lady Sandra Torres (68% to 32%) in the run-off vote for the Central American nation’s next president.

In the months leading up to the elections, the previous president and vice president resigned and were jailed on corruption charges, along with dozens of other government officials. At least 10 members of the Congress of Guatemala and several judges are under investigation.

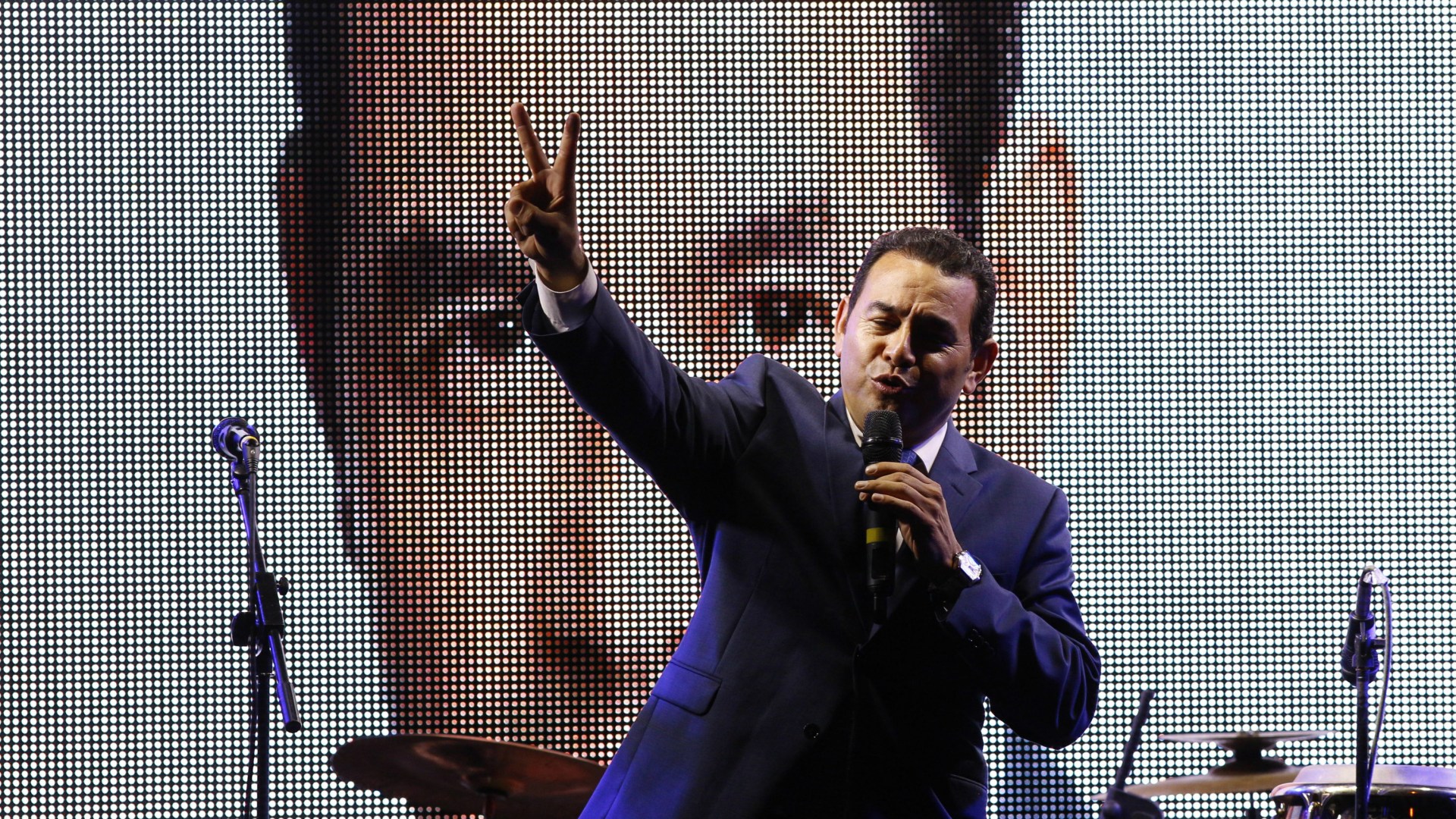

Morales, best known in the past as a TV entertainer, has been characterized as a “comedian.” But it would be more accurate to call him a media personality, actor, producer, and businessman.

He has an MBA, a master’s degree in media and communications administration, and a master’s in high level strategic studies on security and defense. He also holds a degree in theology from the Baptist seminary in Guatemala City. He has been a university professor and founded several businesses.

In his first incursion in politics, four years ago Morales ran for mayor of Mixco, one of the larger townships that make up the metropolitan area around the nation’s capital. He came in third. In 2013, he became general secretary of a small party, the National Convergence Front, and later its presidential candidate.

In April, Vice President Roxana Baldetti and several other high officials were accused of stealing millions of dollars of customs fees. She resigned and was arrested, along with the entire governing board of the Guatemalan Social Security Institute hospital system, after a number of dialysis patients died—apparently from tainted medications.

Morales built his campaign around the slogan of “neither corrupt nor a thief.” As further scandals came to light, a small group of social media-savvy young people started a campaign that brought thousands of protestors to weekly marches against the regime. At the same time, thousands of Christians were praying for a peaceful resolution, with regular vigils in the Central Plaza.

Four days before the September 6 general elections, President Otto Pérez Molina, facing indictment, resigned and was arrested. Buoyed by a massive rejection of politics as usual, Morales garnered 24 percent of the vote, followed by Torres with 20 percent. The front runner-up until a few weeks before, Manuel Baldizón, who had outspent Morales 100 to 1, came in a close third.

With both Baldizón and Torres, the ex-wife of former president Alvaro Colom, perceived as very much part of the traditional system, Morales was the anti-candidate.

Between 35 percent and 40 percent of Guatemala’s population is evangelical, but it is hard to know the true effect of religion on the election. The other clearly identified evangelical in the race, Zuri Rios, daughter of former head of state Efrain Rios Montt, came in a distant fifth. Morales was on record as opposing same-sex marriage and abortion, but most of the other candidates took similar positions.

Many Christian leaders would credit prayer with helping the country navigate through the crises without major violence or a breakdown of the constitutional process. When Perez Molina resigned, the vice president (elected by Congress to replace Baldetti after she stepped down) was seamlessly sworn in. Although democracy is still fragile in Guatemala, this was a sign it has survived and matured over the past 30 years.

Guatemalan evangelicals have traditionally been wary of politics, and some churches have disciplined members who ran for office. But the Evangelical Alliance of Guatemala (EAG) has been part of the “Group of Four,” along with the Catholic Church, the Human Rights Ombudsman, and the National University. As such, they have had a significant voice in discussions with government leaders, politicians, and other significant actors throughout the recent crisis.

“As the major representative of the evangelical church in Guatemala, we have been careful to keep our distance from Morales,” says EAG president César Vásquez. “We know he faces incredible pressures. We want to offer him the same support we would give to whomever might have won."

Morales’s victory inevitably brings to mind Guatemala’s two previous evangelical presidents: Gen. Efrain Rios Montt, still a very controversial figure after his 17 months in power in the early 1980s, and Jorge Serrano Elias.

Like Morales, Serrano Elias came from behind to make it into a runoff election, and won with a significant popular majority (but only a handful of congressmen from his party). The opposition groups he defeated blocked him repeatedly in the legislature, making it almost impossible to govern. When his attempt to dissolve Congress and pull off a Fujimori-style coup failed, he was forced to resign and go into exile.

In some respects, Morales faces even larger challenges, without Serrano Elias’s political skills and Rios Montt’s ability to rule by decree.

Rios Montt, who suffers from Alzheimer’s, is being tried for genocide stemming from massacres committed during Guatemala’s civil war (which was at its height when he came to power as the result of a military coup). Many Guatemalans, including a majority of those living where the genocide is alleged to have happened, still view him as the savior of the country who stopped Marxist insurgents.

“The problem with Montt and Serrano,” says Christian attorney René Lam, “is that when they got into office they forgot their convictions. We hope Morales can really live out his faith and literally give his life for Guatemala, but it will not be easy.”

There is a lot at stake and a lot riding on Morales’s shoulders. The economy is in tatters. Government coffers are bare. A good number of re-elected members of Congress are tainted. Crime and insecurity—fueled by gangs, extortion, and drug trafficking—are off the charts.

So it may be a bit premature to cry victory. Although there is recognition that no one person can fix the nation’s problems, Morales’s failure to meet expectations could bring a backlash.

“We really need to uphold Morales before the Lord,” says Virgilio Zapata, a leader in the national prayer movement and founder of the America Latina Christian High School from which Morales graduated.

Four years ago, Morales and his brother Sammy produced and starred in a movie, El Presidente de a Sombrero (“The Good-Guy President”), in which the characters they played in their TV comedy show, Nito y Neto, decide to form a political party and run for president. In the process they come up with a novel idea: stop lying like all the other politicians, and tell the voters the truth.

Through a series of circumstances, they come to lead in the polls. Just before the elections, with victory all but assured, they announce they are resigning. When asked why, they reply simply, “We are not qualified to govern.”

Guatemalan evangelicals hope and pray that in real life, Jimmy is.