I made the confession while leaning over the coffee table weighted by her enormous family Bible: "Grandmother, I think God is calling me into ministry… and I've decided to go to seminary."

I (Still) Believe: Leading Bible Scholars Share Their Stories of Faith and Scholarship

HarperCollins

256 pages

$18.04

Local preachers had enjoyed warm hospitality in her home for decades. But I knew my announcement would meet with disfavor—I had used the word "seminary." And indeed, she berated me as one who had chosen a foolhardy and perilous course.

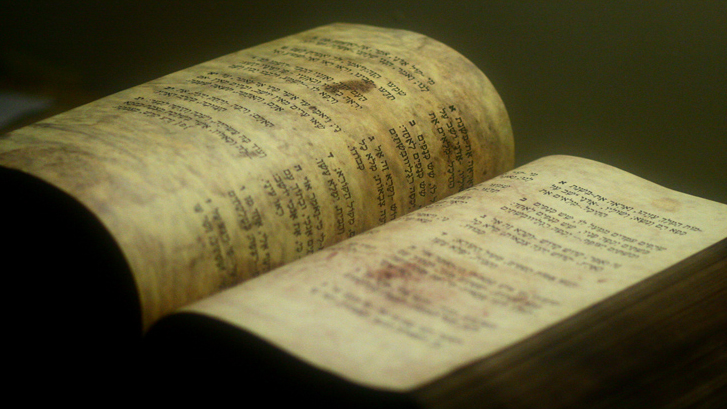

My grandmother believed every word in that King James Bible positioned between us, the browning edges of old obituary clippings and baby announcements protruding from the sides. But in her mind, the “academic” (that is, dry and highfalutin) study of the Bible held no vocational validity in bona fide Christian ministry. True ministers did not require a seminary education.

Testimonies of Another Sort

It’s easy to dismiss the rants of an old woman worried about the Bermuda grass in her day lilies. But the anti-intellectualism underlying my grandmother’s warnings, so deeply embedded in the American psyche, is not without warrant. The academic study of the Bible has a well-earned reputation for hurling students and scholars alike beyond the safe boundaries of orthodox faith.

Years later (after gaining that seminary degree) I became a campus minister. In this position, I found myself frequently reaching out to students undergoing crises of faith after learning from a religion professor that Moses did not really write Deuteronomy or that the Gospels' resurrection accounts differ irreconcilably. My grandmother's warnings had firm grounding in countless testimonies about the hazards of academic biblical studies.

But testimonies of another sort abound, and many fine examples are gathered in a new volume called I (Still) Believe: Leading Bible Scholars Share Their Stories of Faith and Scholarship (edited by John Byron and Joel N. Lohr). Though headlines are made when a Bible scholar trespasses the hedges of accepted belief, there are countless men and women of vibrant faith undertaking biblical scholarship for the church’s enrichment.

I (Still) Believe compiles brief autobiographical accounts from prominent scholars who (still!) believe in the God of the ancient texts they study and teach. These distinguished exegetes not only still believe, as if the best one can hope for after a lifetime of serious biblical study is a threadbare retention of Christian faith. Even better, their stories offer examples of what happens when one chooses to dwell believingly, decade after decade, within the wondrous yet terrifying world of Scripture. Though the Word of God is like a reviving breath that rattles dry bone piles and re-pieces them into living armies, biblical writers also liken it to a hammer that shatters rock, to an uncontrollable fire, to a blade sharpened to surgical precision. Persistent engagement with the revelatory words of God makes for a life of joy—but also a life of wounds.

For these essayists, the wounds in question haven’t come from losing faith, but from embracing it. Brokenness and pain are universal on this side of Eden’s barred gates, and a number of these scholars recount times when God revealed himself as one who gives but also takes way. (The reflections from John Goldingay and Walter Moberly stand out in this regard).

For others, the wounds emerge from expectations within the academic guild clashing with a love for Scripture. Torn between the two, Phyllis Trible clings to the Bible like Jacob gripping his divine combatant in the night by the Jabbok:

"I will not let go of this book of words unless it blesses me. I will struggle with it. I will not turn it over to my enemies that it curse me. Neither will I turn it over to my friends who wish to curse it. No, over against the cursing from either Bible-thumpers or Bible-bashers, I shall hold fast for a blessing. But I am under no illusion that the blessing will come on my terms—that I will not be changed in the process. After all, Jacob limped away."

While the eighteen "testimonies" in I (Still) Believe are marked by joys and triumphs, they also offer varying accounts of this mighty and beautiful wrestling and wounding.

Skilled Listeners

Anti-intellectualism in American religious culture is fuelled in part by a destructive cycle: Academics embittered by the church delight in puncturing the illusions of young Christians under their tutelage, who often retaliate by defensively reciting theological platitudes that fit on a coffee mug or t-shirt but bear no credible weight in a classroom, or perhaps anywhere else. (The student’s recourse to “my minister says” or “the Bible is inerrant” only confirms the illusion-puncturing academics in their self-appointed role of holding the line against anti-intellectualism.)

Refreshingly, the contributors to I (Still) Believe are not writing with axes to grind. But they do write honestly about wounds that often come not from secular higher education, but from the church they have sacrificed a great deal to serve. There is much to learn from Gordon Fee's casual reference to being summoned before heresy hearings by his denomination, and from the pressured departures of Andrew Lincoln and J. Ramsey Michaels from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary (though from an earlier chapter in the school's history).

Speaking as one torn personally between pastoral ministry and academic work, I wonder if many of today’s tensions between church and academy flow from a resistance to certain vocations and gifts within the Body of Christ. Popular theological platitudes are consoling because they are more immediately digestible and require little in the way of deeper reflection. But oversimplified propositions splinter into shards when colliding against the harsher and more complex realities of life.

So we need the voices of those who inhabit that wondrous and terrifying world of Scripture, where sacred books list propositions, proverbs, and regulatory laws—but also disturbingly narrate scenes of a man raising a knife over his cherished son, of an unnamed concubine mauled without any hint of redemption, of a refugee teen fleeing to Egypt clutching the tiny frame of the Messiah, of divine speech voiced as easily from a tornado as from a pagan sorcerer's donkey.

Seasoned Christian Bible scholars who do their craft well are often the church's most skilled listeners to that life-giving and life-altering Voice from these sacred texts. Dismissing their counsel can effectively dismember parts of Christ's body—perhaps ears or eyes—that the Holy Spirit has positioned indispensably within the family of faith.

We need our biblical scholars and theologians. Of course, we also need theology grounded in careful listening to our culture, congregations, and neighbors—theology enthralling enough to lead us into worship and compelling enough to encourage a robust life of faith.

For Walter Brueggemann, it is not theology but a lack of theology that threatens this kind of life. As he puts it, crises of faith often result "because we are tempted to settle for small packages of certitude" that are "encoded in small formulations of truth." Scot McKnight laments that "many believers walk away more often because of the superficial theology of Scripture they were taught in conservative circles." Beverly Roberts Gaventa never felt her faith threatened in academia because she did not inherit a belief system "constructed out of propositions, like so many toy building blocks, each of which is necessary in order to keep the whole edifice in place." Donald Hagner notes the irony "that the concessions and modifications of my early conservatism have paradoxically enabled me to retain my faith and commitment."

Christian sceptics of academia could perhaps label such statements as acts of "compromise." More likely, these comments are wise reflections premised on long years of faithful listening.

The Lure of Scholarship

During almost a decade of campus ministry, I pastored a small rural church. I remember walking from the parsonage one evening to teach the Wednesday night Bible study, having just received yet another rejection letter from a PhD program in New Testament.

"What's wrong, pastor?" Aunt Martha asked, noticing my poorly hidden gloominess (she was not my real aunt, but that's how we all knew her).

"Well, I just got another rejection from a graduate school."

"Oh good! I've been praying against all your applications!" She made no attempt to hide her delight.

It was a strange sort of compliment—the entire congregation knew I was considering an academic vocation, but Aunt Martha wanted me to stay on as pastor. Why would I leave a job where I could teach and preach Scripture in a way that impacts the lives of solid workaday folks? Why, instead, would I aspire to hole myself up in an office, writing books and articles only academic types would care to read?

Why, indeed. It is an urgent (even if overly simplistic) question that plenty of the contributors to I (Still) Believe had to wrangle over in their own lives. Many of them actually stumbled into a scholarly vocation after having first embraced a call to ministry. James Dunn had been making plans to serve as a missionary in India. Scot McKnight had the mission field of Europe in his sights. Gordon Fee was heading toward Japan. Others were envisioning a life of ministry in a local parish.

Were they vocationally derailed by the lure of scholarship? (Was I?)

This book should not necessarily be read as an unqualified defence of the scholarly life. Its contributors certainly exemplify how that route can be faithfully pursued with the kingdom of God as a central focus. But, more so than even their non-academic critics, these writers are aware of the spiritual hazards that have lined their chosen career paths.

There are even serious critiques levelled against the scholarly life. McKnight's frustration over what he sees as the futility of our current model for theological education has radically reshaped his writing strategy. For those of us eager to grip the plowshare of academic biblical studies, Gaventa's words are especially sobering: "I haven't so much doubted God as I have doubted the significance and contribution of biblical scholarship," a confession to which my grandmother (now dearly missed) would likely say "amen."

Then again, the formative impact of these scholars on students now leading churches and teaching other teachers throughout the world is incalculable.

Believing More

In spite of Aunt Martha's prayers, I now find myself spending more time writing academic papers and preparing lectures on New Testament Greek than visiting parishioners in the hospital, officiating funerals, or teaching Wednesday night Bible studies. I admit that some of my grandmother's misgivings are proving true. Contemporary biblical scholarship can sometimes promote, in Gaventa's words, an "ethos of self-promotion" and an "agonistic culture that undermines genuine learning." As Edith Humphrey points out, there is constant professional pressure "to be recognized as clever, or novel, or seminal."

So why do I dare to linger in the terrifying (and often wonderful) world of biblical scholarship? Because Scripture itself is so wonderful. Because the aspiring pastors sitting in my Greek class will one day preach to skeptical grandmothers and visit aunts in hospitals. That's when they will need denser, more powerful words than their own. In lashing myself and my students to the words of the Bible, my hope is not only we will still believe after a life of rigorous study, but that we will, as Humphrey puts it, "believe more."

Andrew Byers teaches biblical studies and missional leadership at St John's College, Durham University. He is the author of TheoMedia: The Media of God and the Digital Age (Cascade Books) and Faith Without Illusions: Following Jesus as a Cynic-Saint (InterVarsity Press), and he blogs at hopefulrealism.com.