The plot to Ave Maria is as improbable as it is provocative. A Jewish settler family crashes their car into a statue of the Virgin Mary at a Palestinian Carmelite monastery in the West Bank.

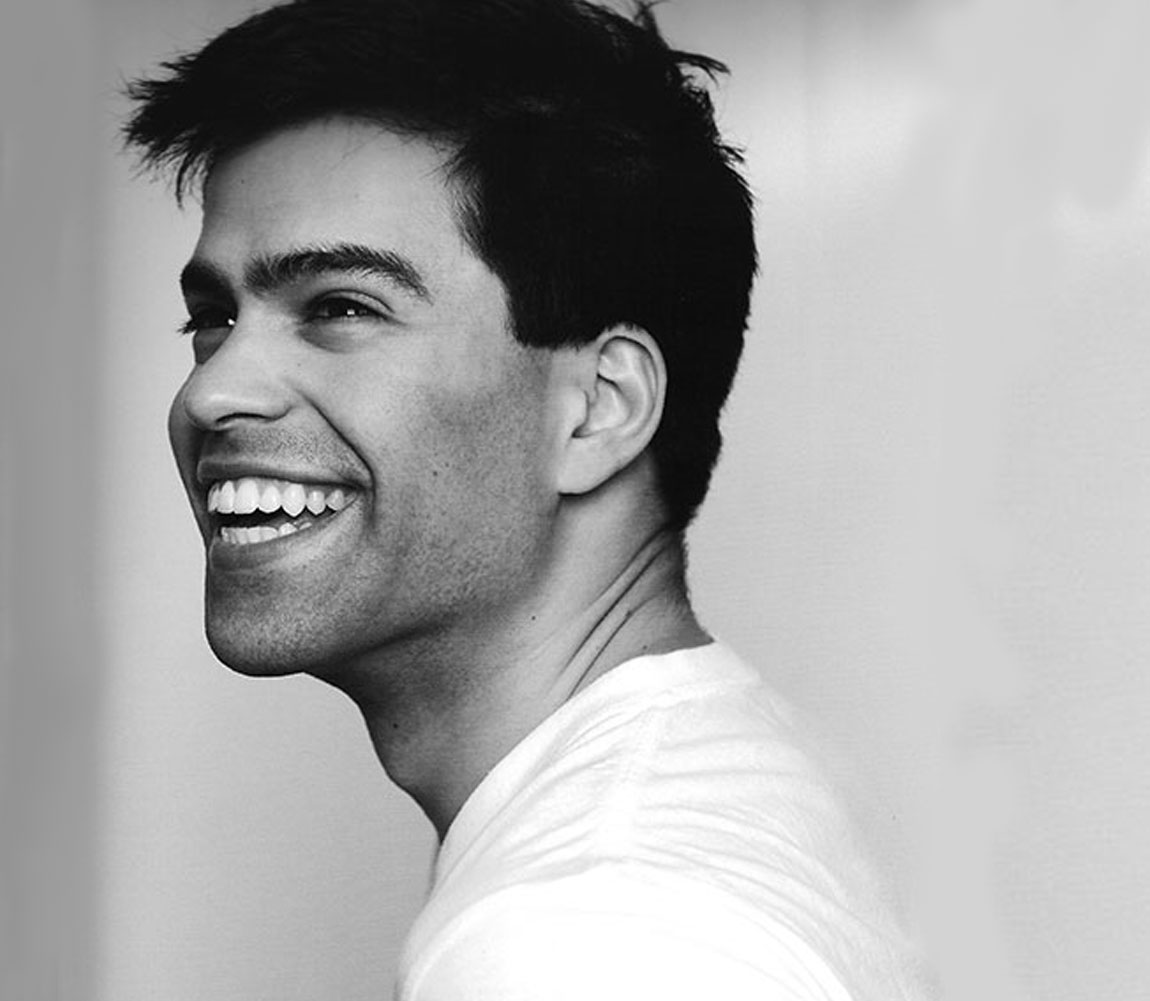

Bound by the onset of Sabbath, the Jews can do little to get home. Bound by a vow of silence, the nuns can do little to help. Bound by mutual distrust and annoyance, the odd couple pairing can do little but bicker. Fortunately, spellbound by the comedic touch of 34-year-old producer Basil Khalil, critics around the world can do little but laugh.

This 14-minute short (trailer below) already won top prizes at film festivals in Grenoble, Montpellier, and Dubai before securing a nomination for best live-action short film at this year’s 88th Academy Awards.

Ave Maria is Khalil’s second comedic venture into the deeply divisive and often somber portrayal of the Arab-Israeli conflict. His 2005 Ping Pong Revenge illustrated the cycles of misery each side inflicts on the other, but in the style of a satirical musical.

Khalil’s short film is not the only recent cinematic foray into the lives of Middle East Christians. The widely acclaimed documentary Open Bethlehem is a passionate account of efforts to intervene in the city’s tragic decline. May in the Summer mirrors Ave Maria‘s mix of religious tension and comedic drama as a successful Jordanian Christian author returns home to marry her Muslim fiancée and runs headlong into deep-seated cultural taboos.

Khalil knows them well. The son of a Palestinian-Israeli father and British mother, he grew up in Nazareth, near a Carmelite monastery not unlike the one in his film. Oddly enough, he was not allowed to watch movies as a child, developing a love of storytelling from his mother’s reading classic tales to him instead. His father is an evangelist in the Brethren church and runs the well-known Emmaus Bible School in Arab Galilee.

The London-based director developed an international perspective after studying filmmaking in Scotland and living in Italy and Spain. Though his upbringing was fused by faith, Khalil confesses to growing more cynical toward organized religion. CT interviewed him about regional issues, his religious motivations, and the film The New York Times called "the Middle Eastern answer to ‘Curb Your Enthusiasm.’”

In the United States the conversation about the Arab-Israeli issue is usually in terms of politics, tension, and conflict. What led you to produce a comedy?

I wanted to make a film that’s entertaining, approachable, and that people would come out with some new information. Through comedy, people are more likely willing to sit through it than a heavy preachy political drama.

As I watched the film, though I appreciated the humor and humanness of the characters I also sensed their deep frustration. Is such frustration inescapable given social and political realities?

There is frustration for sure. The man-made rules these two sides have taken upon themselves get in the way of the most basic tasks, talk. On the other hand you have the issue of the master and the servant, where the occupiers and master of the land now needs help and is at the mercy of the people they are used to be in control of. I can’t imagine a more awkward situation for someone to be in.

Given the critical acclaim for Ave Maria, do you think the audience is clamoring for a different take than the typical Hollywood approach to Middle Eastern issues?

I didn’t set out to patronize or criticize, but just display realities, as absurd as they may be. I let the situation play out in front of an audience who identify with the issues the nuns and settlers face because they are also universal issues—lack of communication and extreme religious rules.

You were raised by a Palestinian Christian father and a British mother, were you comfortable in both settings?

You don’t really choose where or how you’re born, so you just live with it and make the most of it. I do believe being of both worlds did give me a more critical perspective. I know what and how the west sees us, and I’m able to give them something fresh, yet at the same time I know our stories and culture from Palestine that I’m able to portray accurate stories from there.

Sometimes the Arab-Israeli issue is seen in terms of Muslim versus Jew, glossing over the Christian presence. What does your film communicate about Arab Christianity?

Nearly at every festival screening I would have people walk up to me and tell me this is the first time they’ve heard about Christian Arabs—from Taiwan, Germany, and France to the USA. I am glad that I was able to shed some light on the diversity of the Middle East and remind them that Christians have existed there for centuries.

It is so easy to sensationalize and generalize Arabs in the news as evil militants, which I call lazy journalism, however it is a constant struggle for us as we try and get our voice heard. We are humans, normal people as interesting and as boring as everyone else. Unfortunately the extremists make better ratings, and they’ve hijacked the agendas.

The nuns in the film are put out and annoyed, yet they both help and choose to trust the settler family. Is there a Christian message in the film? Is there a Christian message for the region?

The nuns have taken a vow of charity, and they cannot refuse someone in need. In this story, they’re stuck with this squabbling family who disrupts their routine of silence, they choose to ignore them at start, but when they become too loud the nuns have to break their rules and cooperate so that they can get rid of them and return to their silence. Therefore you see them bend the rules in order to return to their strict rules. Makes one questions how important are these man-made rules?

How does your Christian upbringing influence your work?

The thing that most influences my work is life experience. Film is about emotions. You direct a film for people to watch and feel things as they’re sitting in a dark cinema. One can’t convey these feelings unless they’ve felt them in real life.