“Your first 200 sermons are going to be terrible.”

I recall hearing this frank assessment from Tim Keller as a young seminarian crammed into an auditorium filled with other aspiring preachers. Immediately we started calculating. How many more sermons did we have left until we hit the 200 mark?

You can quibble with the 200-sermon number but preaching really is a craft. And like all crafts, it’s takes tons of practice to become proficient.

I’m grateful for the patience and kindness of Covenant Chapel, my first church out of seminary. The people of that congregation put up with my fastidious, line-by-line, manuscript preaching. Their uncritical listening was a grace to me. Thankfully, as year after year of preaching went by, my preaching started to slowly relax and become more natural. As I did my best to put together biblically faithful, culturally engaging, pastorally sane sermons week after week, something happened. Instead of woodenly moving from exegesis, to outline, to manuscript, I began to adopt more creative sermon prep practices. One of those involved putting pencil to paper.

After completing exegesis, I found myself abandoning the computer for sheets of paper. I began filling them up with diagrams, thought bubbles, and clusters of material wedged into the corners of 8 ½ by 11 sheets. I tried to use journals, but felt too restricted by their limited area. Something different happens in the tactile experience of pressing graphite to paper.

I tried to use journals, but felt too restricted by their limited area. Something different happens in the tactile experience of pressing graphite to paper.

As I take the exegetical idea from my passage, and try to wrestle three points, or four scenes—something, anything—out of it, I generate many unused ideas, phrases, directions, and illustrations. There’s lots of heat but fortunately there’s also some light. By the end of the process, somehow I’ve moved from a block of wood to fairly defined structure, with some inspiring detail in areas.

Applying Pencil to Paper

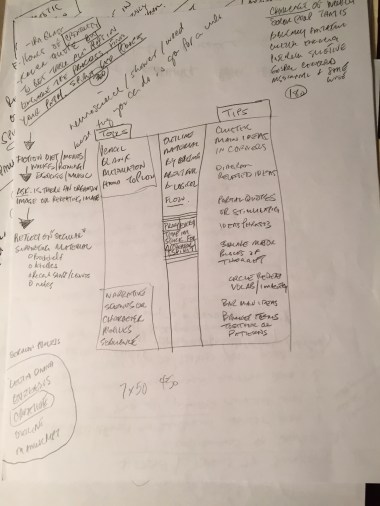

A few tools I repeatedly lean on: cluster corners, diagrams, stimulating phrases, circled imagery, and bracketed patterns (see examples embedded in this article).

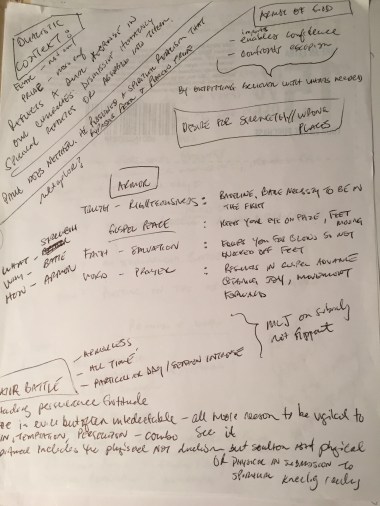

First, let me explain the cluster corners. I tend to cluster similar ideas of substance in corners of a sheet. When I have a name for that cluster I put a box around its title. For instance, when I was preaching the armor of God passage in Ephesians 6, one corner listed ways that we dismiss spiritual realities or are utterly absorbed into them. I thought about how we can go through life operating on secular power, relying on reason and strategy, or spiritual power, pasting Bible verses and “have more faith” on our problems. Both amount to rejecting the armor of God in favor or self-made armor. To encapsulate this idea, I wrote down the words, “Dualistic Context,” and boxed them.

This corner ended up being the first third of the sermon and lead to the breakthrough idea of “spiritual realism.” Spiritual realism, as I defined it, is using faith and reason to thrive in the war of life. Paul tells us, “Finally, be strong in the Lord and in the strength of his might” (Ephesians 6:10). His solution to temptation and sin is not to close your eyes and wish it away by “faith,” but for Christians to personally resolve to be strong. It requires personal effort, which is matched up with “the strength of the Lord.” This pattern of combining real personal effort with genuine spiritual strength repeats. We need faith and reason, resolve and grace, to fight against spiritual powers.

The second tool I like to use: diagrams. Sometimes I diagram a spectrum, drawing a line across the page, tipped with arrows. In a message on the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5), I put “literal” at one end and “attitudinal” at the other end. These two ends of the spectrum helped me see two ways that the Sermon on the Mount is often misinterpreted. For this article, I actually drew a smaller version of the sheet of paper in the middle of the sheet, and divided it up into sections to organize my thoughts. A list of tips formed in a column to the right. A corner cluster is in the upper left that focuses on tools.

As ideas churn and similar things get grouped, stimulating phrases emerge that often end up being key phrases or repeated vocabulary in the sermon. For the armor of God sermon, I wrote “prayer is not restricted to one piece,” which I used to explain that “praying at all times in the Spirit for all the saints” is so powerful and pervasive that it doesn’t even need a single piece of armor. People have come up to me several times commenting on how helpful that observation was and how they’ve been praying more. I could have just said, “Pray a lot. Paul says to pray all the time.” But this “stimulating phrase” stuck with people and communicated the same idea in a fresh way. I may not have landed on these phrases if it weren’t for my habit of capturing them with pencil and paper.

Sometimes a sermon has important imagery that is carried throughout. When this happens I circle the imagery. In a sermon on worldviews, I talked about how we all stand on a branch to support us, but asked, “Can that branch carry our weight?” The branch is your worldview, and only the truth makes it sturdy. I came back to that image throughout the sermon. In a sermon on the crucifixion (Matthew 25), I circled the narrative scenes I wanted to preach through and attached an emotion to each one: Scene 1: Scorn of Christ (light) / Scene 2: Seriousness of the Cross (Dark) / Scene 2.5: Our response / Scene 3: The Better Spectacle (Awe/Fear). Under each scene I bulleted major events or actions to help me organize my retelling of the narrative.

When I bracket or bullet, I know things are starting to come together. At this stage, the main ideas are starting to take form, and I can now put supporting material under them. This is a stepping stone to the sermon outline, and I drag and drop these bullets into major points or sub-points, giving the whole sermon a logical flow.

Throughout the process it’s vital that we pray. Dependence on the most creative Person in the world, the Holy Spirit, enables us to not only improve the way we communicate God’s Word but to encounter him in the process.

In the end, our goal in preaching shouldn’t be creativity per se, or even simply to be a great preacher. You can be a master communicator and yet fail to communicate the gospel of grace. Still, our goal should always be to communicate the inexhaustible riches of Christ and the hope of the gospel as clearly and as compellingly as possible. And using the above techniques enables me, at least, to do that more effectively.

For more tips for infusing your sermon prep with creativity, read Stop Starting with the Text.

Jonathan Dodson is the founding pastor of City Life Church in Austin, Texas. He is the author of Raised? Finding Jesus by Doubting the Resurrection and The Unbelievable Gospel. He is also the founder of GospelCenteredDiscipleship.com.