Professors at my former seminary in Kentucky were obsessed with fountain pens. Coming from New Mexico, where my teachers had sported ripped jeans, bandanas, and Teva sandals, I initially found this passion a bit hoity-toity. One day, however, when I voiced my reservations, one of my professors riposted with a robust defense of penmanship.

As an introverted pastor, he explained, he sometimes found it hard to be personable with his people. He therefore devised a plan to send every member of his congregation a handwritten letter on his or her birthday, practicing hour after hour to overcome his sloppy handwriting and learn the craft of penmanship. (He even showed me the manuals he used.)

Fair enough, I reasoned. But I still saw little difference between a text message and a letter. It wasn’t until a few years later, when I ran into two members of his former congregation, that I saw the value of his efforts. The first thing this couple said after they found out I had classes with him was, “Ooh, we really miss his letters!”

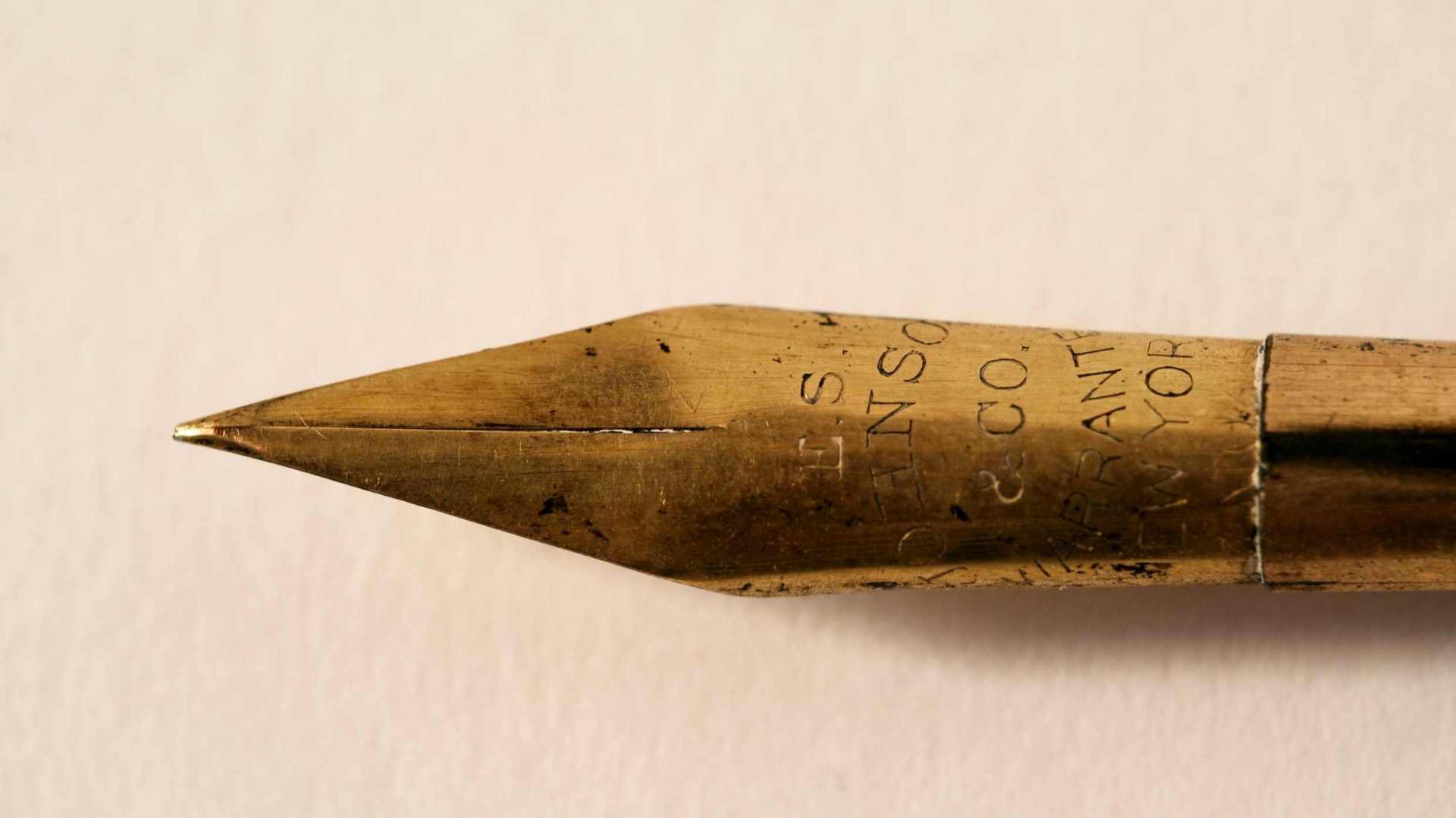

“See with what large letters I am writing to you with my own hand,” Paul wrote to the church in Galatia. It rings weightier than the modern alternative: “See with what ALL CAPS, italicized words, and emojis I am typing to you from my own personal smartphone!” Paul typically dictated his letters through an amanuensis, but he wrote to the Galatians with his own hand to convey the importance of his point: “Don’t be fooled by those preaching a gospel other than the one I, whose handwriting you’re holding in your hands, taught you.”

Church leaders can learn something from Paul and this professor about the power of a handwritten letter to communicate intimate and weighty matters—especially if they want to minister in a special and specific way to older generations who don’t text or email.

I recently came across a letter from the 18th-century pastor and theologian Jonathan Edwards to a woman, Lady Mary Pepperrell, who had recently lost her son. With his page probably illuminated by mere candlelight, he penned about 2,500 words to console her with an extensive reflection on the goodness of Christ. If you want to learn how to write pastoral letters, studying old masters like Edwards isn’t a bad place to start:

[Stockbridge, November 28, 1751]Madam,

When I saw the evidences of your deep sorrow under the awful frowns of heaven in the (then late) death of your only son, it made an impression on my mind that turned my disposition to quite other things than flattery and ceremony. When you mentioned my writing to you, I soon determined what should be the subject of my letter. It was that which appeared to me to be the most proper subject of contemplation for one in your circumstances, and the subject which above all others appeared to me to be a proper and sufficient source of consolation to one under your heavy affliction: and this was the Lord Jesus Christ. . . .

Let us think, dear Madam, a little of the loveliness of our blessed Redeemer and his worthiness, that our whole soul should be swallowed up with love to him and delight in him, and that we should salve our hearts in him, rest in him, have sweet complacence and satisfaction of soul in his excellency and beauty whatever else we are deprived of. . . .

That this glorious Redeemer would manifest his glory and love to you, and apply the little that has been said of these things to your consolation in all your affliction . . . is the fervent [prayer] of, Madam,

Your Ladyship's most obliged and affectionate friend,

And most humble servant,

Jonathan Edwards