Editor’s note: This is the third in a series on the Fibonacci sequence. You’ll get the most out of it if you read parts one and two first.

“To see a world in a grain of sand. And Heaven in a wild flower. Hold infinity in the palm of your hand. And eternity in an hour.” —William Blake, “Auguries of Innocence”

If the language of the universe is math, then there’s one poem engraved across scientific fields as disparate as botany, ornithology, and meteorology: the Golden Spiral.

To understand the Golden Spiral, we have to start with the Fibonacci numbers. I explained in previous articles that when we arrange the Fibonacci numbers arithmetically, we obtain the Golden Ratio. What happens when we arrange them geometrically instead?

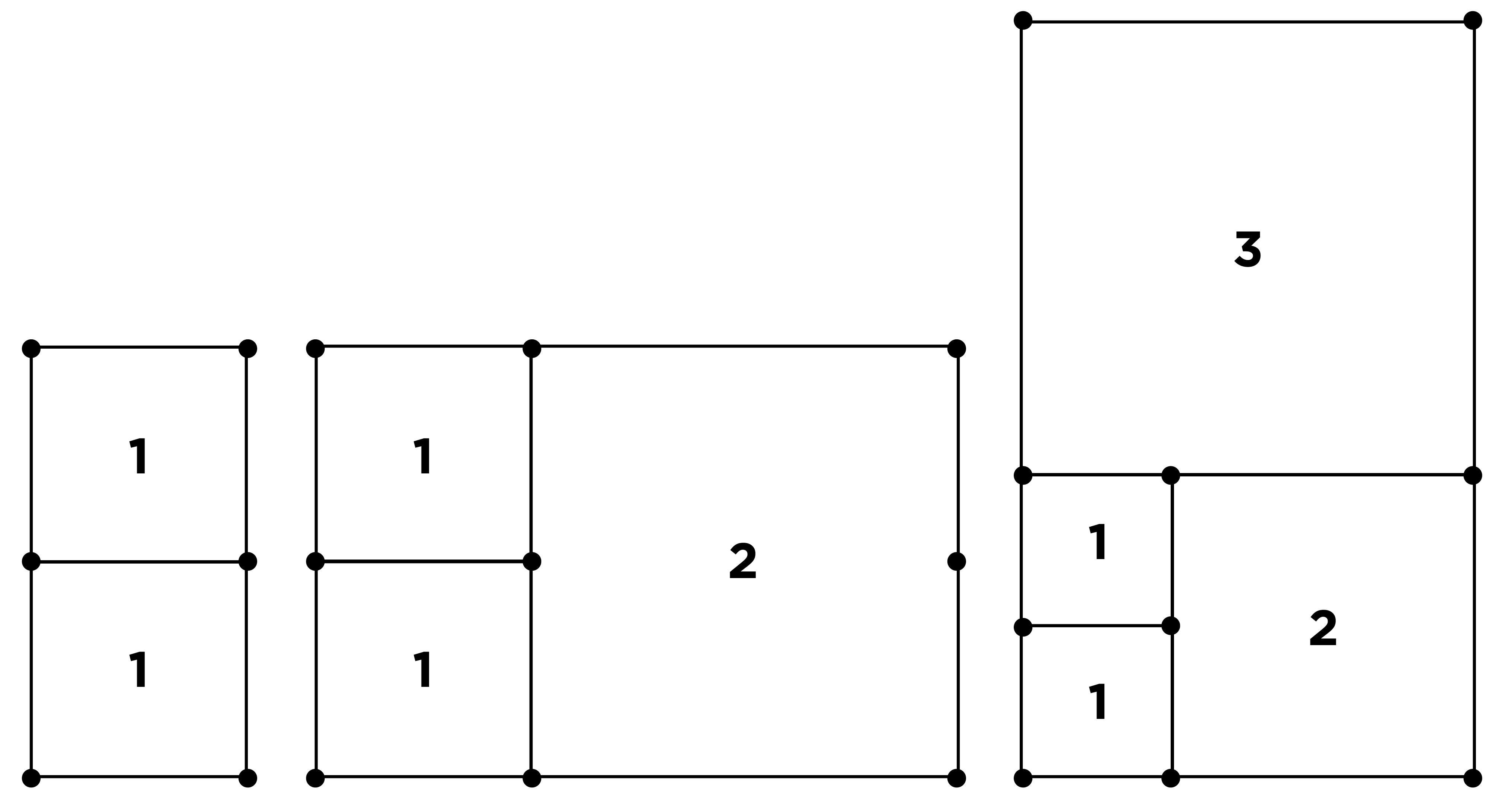

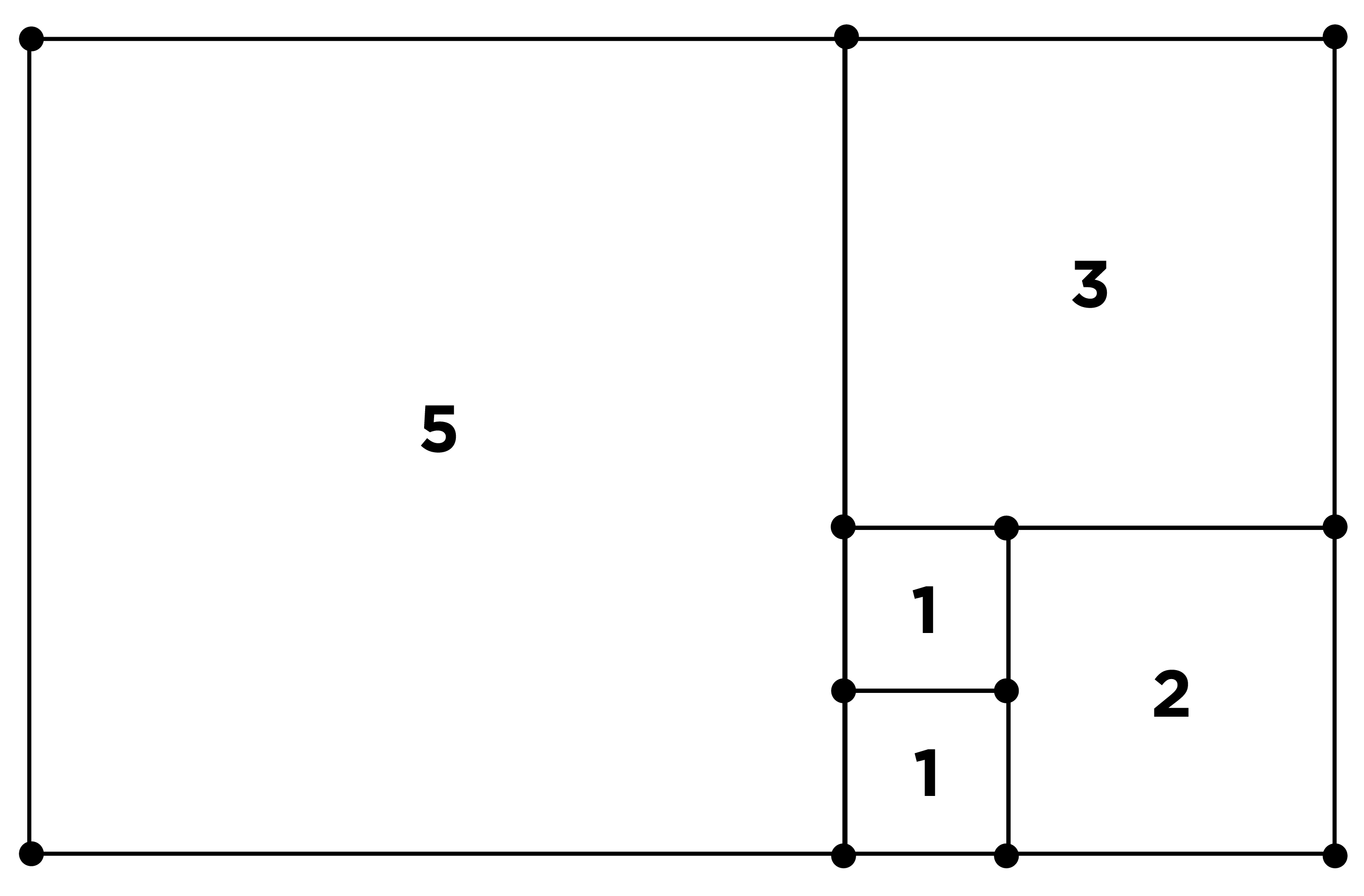

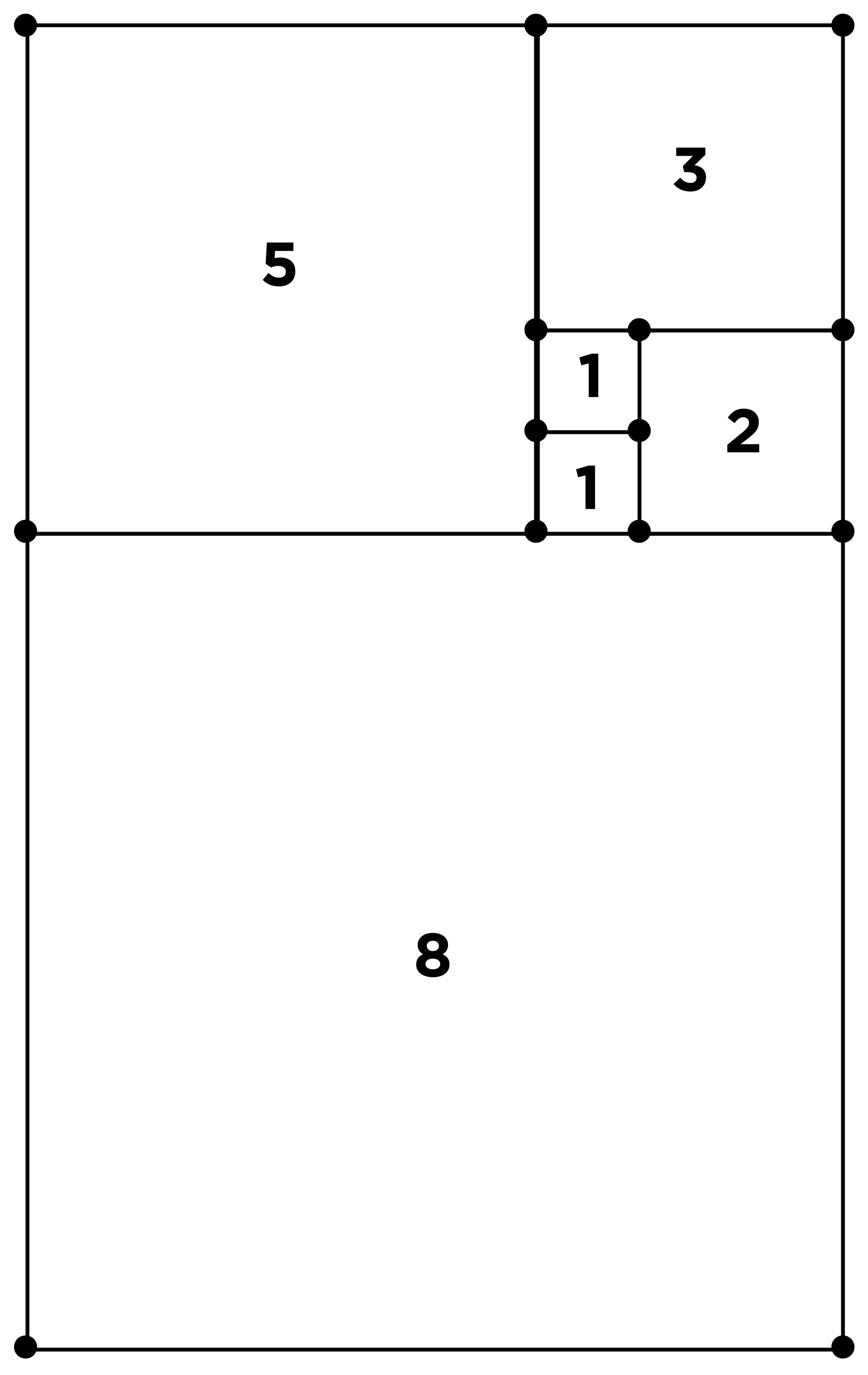

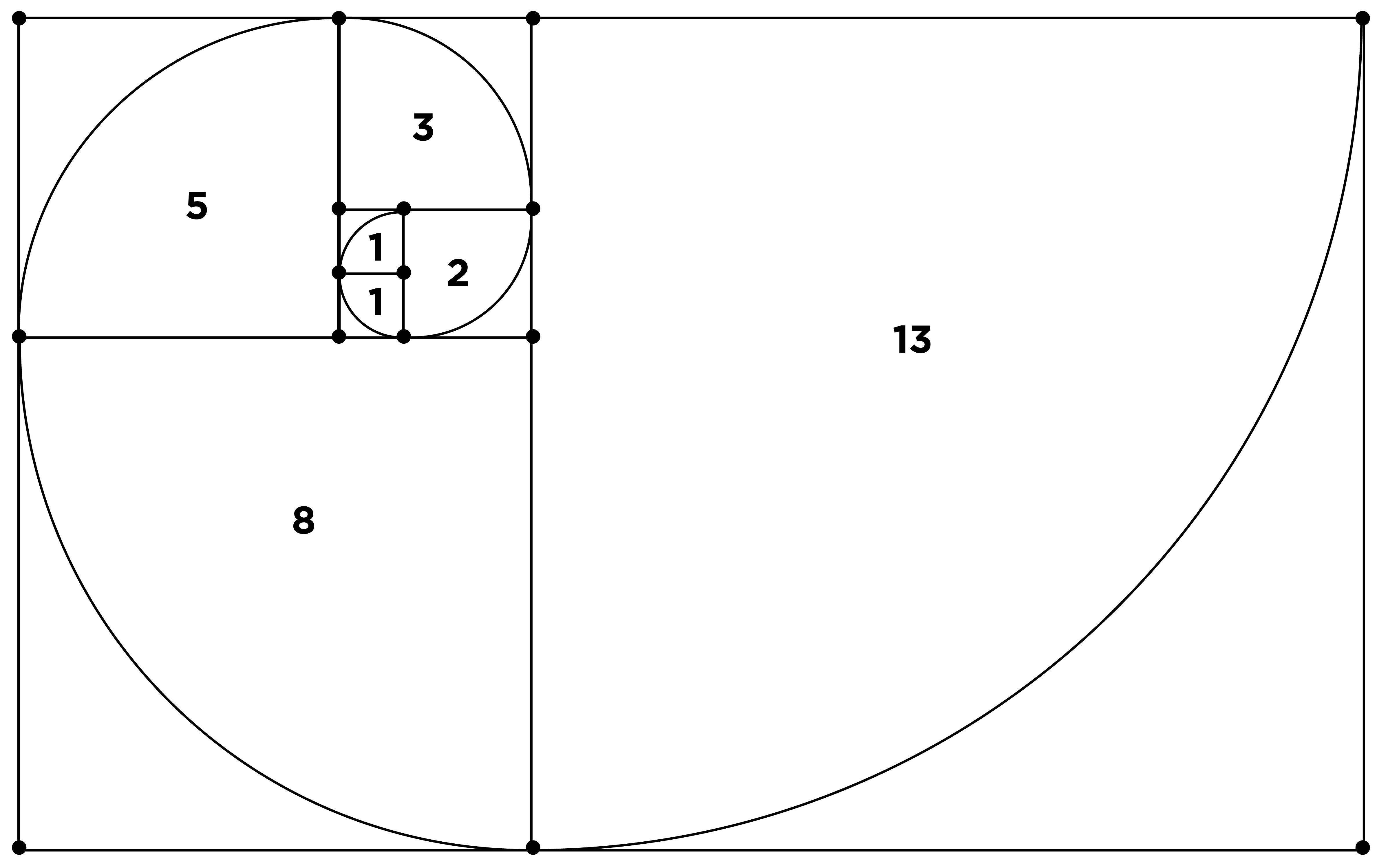

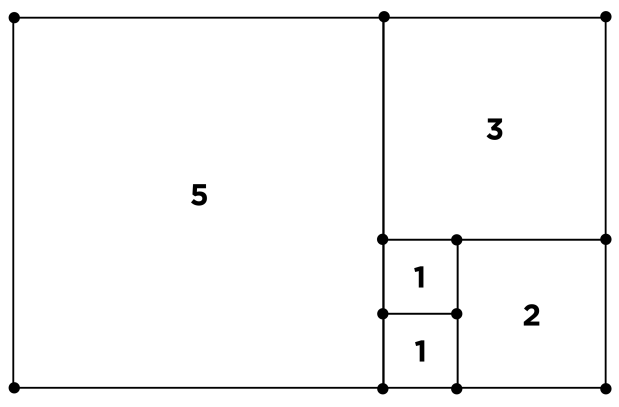

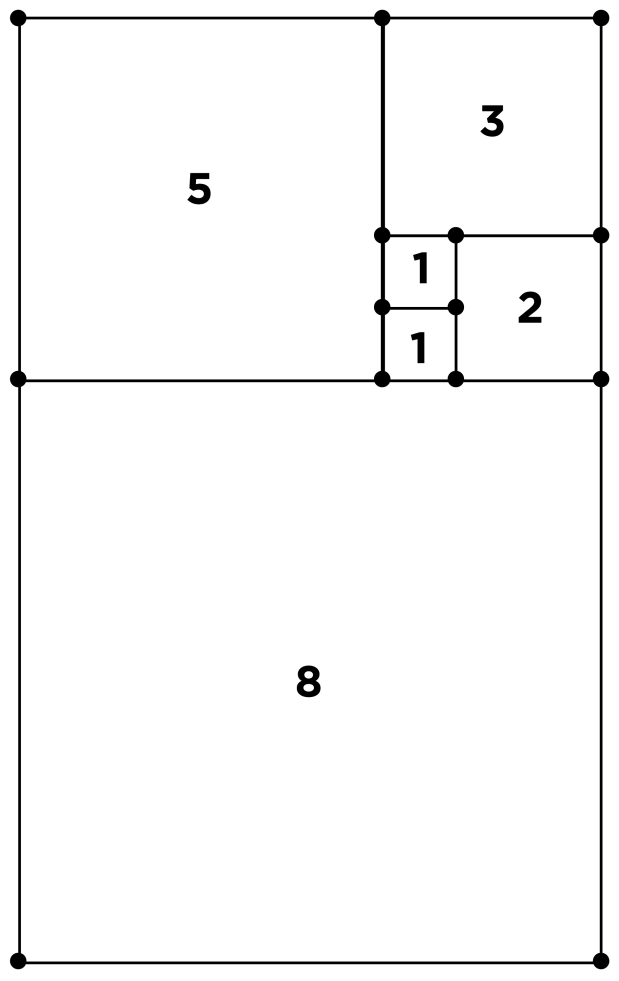

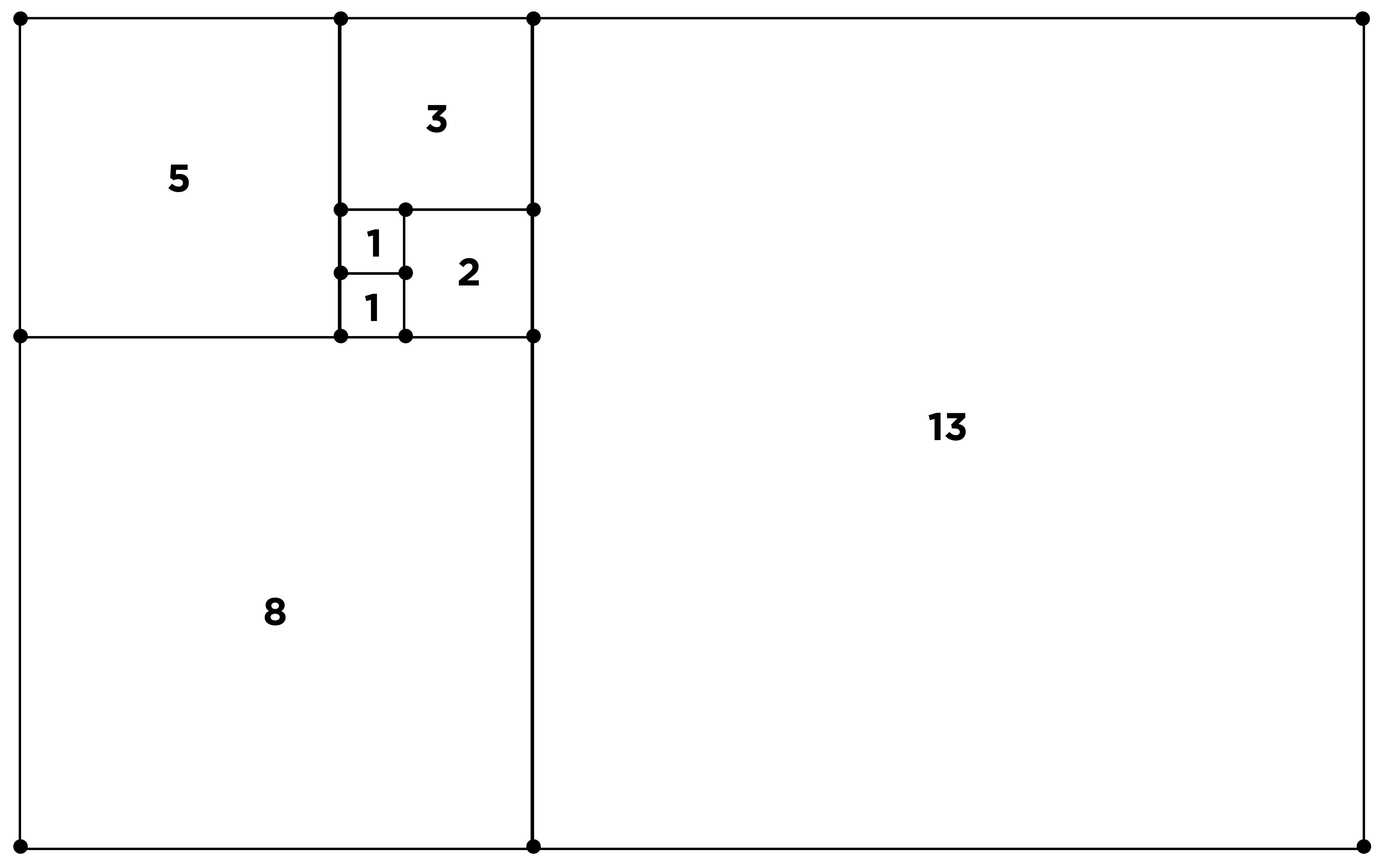

Let’s get to building: We’ll start by taking squares with side lengths the size of the Fibonacci numbers (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13…). We will rotate the squares counterclockwise around each other, building each square off of a side formed by the combination of the previous squares. We can follow the process of the Fibonacci sequence in the increasing sizes of the squares.

This “Golden Rectangle” (so named because the ratio between the length and the width of the rectangle approaches The Golden Ratio with each iteration) is a geometric manifestation of the Fibonacci numbers.

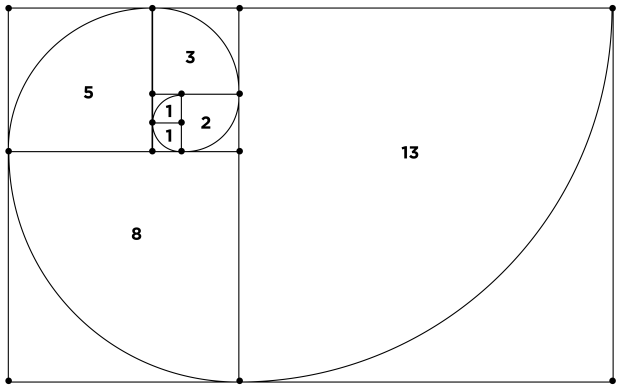

Now go back to the interior squares (1 unit by 1 unit) and connect the vertices of the squares using successive quarter-circles with radii that have corresponding Fibonacci numbers. The interconnected series of quarter-circles is called the “Golden Spiral.” The Golden Spiral is another geometric manifestation of the Fibonacci numbers, and it’s found in nature just as frequently as the Fibonacci numbers are found in botany.

As I’ve explained in my previous article, the Fibonacci numbers occur in botany when “spiraling” occurs. For example, in a tree that doesn’t have all of its branches pointing out in the same direction, the Fibonacci arrangement allows for maximum exposure to the sun in order to maximize the efficacy of photosynthesis.

The Golden Spiral, however, is an actual spiral—not just a way to count rotations around a fixed center point. The same efficiency found in botany is clearly applied in other areas of nature as well. But it’s applied in ways (and for reasons) that we don’t entirely comprehend. It’s there. But why?

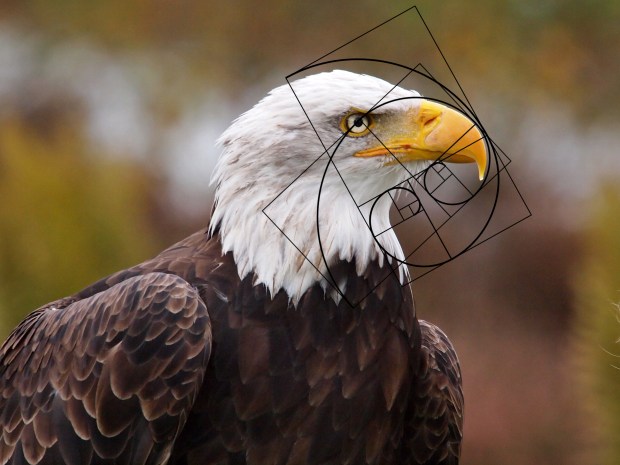

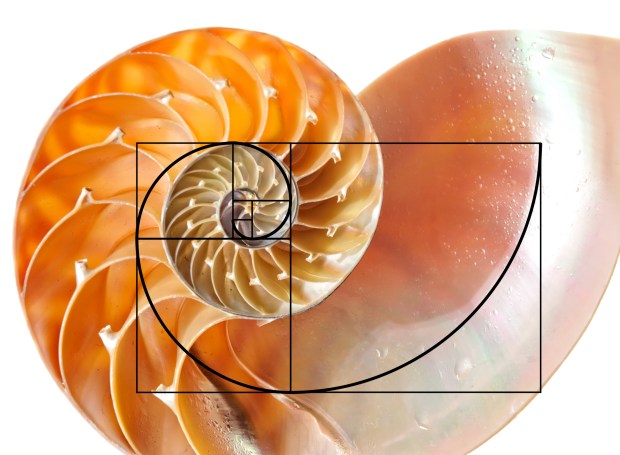

What do a bald eagle, nautilus shell, and a sunflower have in common? It sounds like the setup to a bad “dad joke.” But it’s clear that they’re all built using the same common language, following the path of the Fibonacci numbers as they twist their way towards efficiency.

The curve of eagles’ beaks could easily be much blunter or sharper. But they’re not. They generally follow the Golden Spiral. A nautilus shell could be more tightly wrapped. But it isn’t. It’s a Golden Spiral. Just like with the Fibonacci numbers, there are examples in nature of spiraling effects that don’t follow this Golden rule. But also like Fibonacci numbers, those examples are much harder to find than Golden Spirals. A certain type of spiral is much more prevalent than any other type.

Not just DNA

Even if we don’t fully grasp all the reasons behind the Golden Spiral’s appearance in diverse forms of life, we can at least acknowledge the role that genetics and heredity play. If Mommy Eagle and Daddy Eagle have beaks and heads that follow a Golden Spiral, then we would expect Baby Eagle to have the same. But what about instances where heredity doesn’t apply?

Hurricanes are formed by a confluence of climatological features that replicate themselves frequently at certain times of the year depending on their location on the globe. The details aren’t significant if one is willing to acknowledge that hurricanes don’t have “parents” in the traditional sense. So why should hurricanes share any traits whatsoever?

But they do. As hurricanes rotate, the enormous cloud bands form Golden Spirals. The same spiraling efficiency that allows sunflowers, daisies, and pineapples to survive also allows hurricanes to be formed. But in this case one cannot claim “survival of the fittest” as the hurricane’s motivation. While a hurricane is a natural occurrence, it is not a living being. There are no inherent chemicals dictating the way in which they form.

And spiral galaxies form themselves the same way.

Taste and see

The ancients had another name for the Golden Ratio—they also called it the “Divine Ratio.” Their theology may have been all over the place, but they saw this relationship as evidence of something supernatural. It doesn’t have to be; it’s just as easily evidence of natural selection operating at peak coherence. Those of us who believe in a Creator God, however, can marvel at the complexity shown in this ubiquitous relationship. We have a model of the galaxies provided for us on the head of each sunflower. The nautilus shell tells us of the hurricanes that it witnesses on a yearly basis. Like the Earth’s steady rotation around the sun and the steadiness of a human heartbeat, God often communicates to his children by repeating himself. As humans filled with doubt, how important is it that he repeats himself, over and over again, not only in Scripture but also in his natural revelation?

And how important is it for us to repeat ourselves as well, especially in our praise to him? We long for the day when we can repeat back to him our devotion; one day we will join the chorus, day and night singing “Holy, Holy, Holy.”