Gene editing, brain chip implants, and synthetic blood may reduce the risk of disease, sharpen minds, and improve body strength. But messing around with nature in order to enhance humans isn’t something many Americans are excited about.

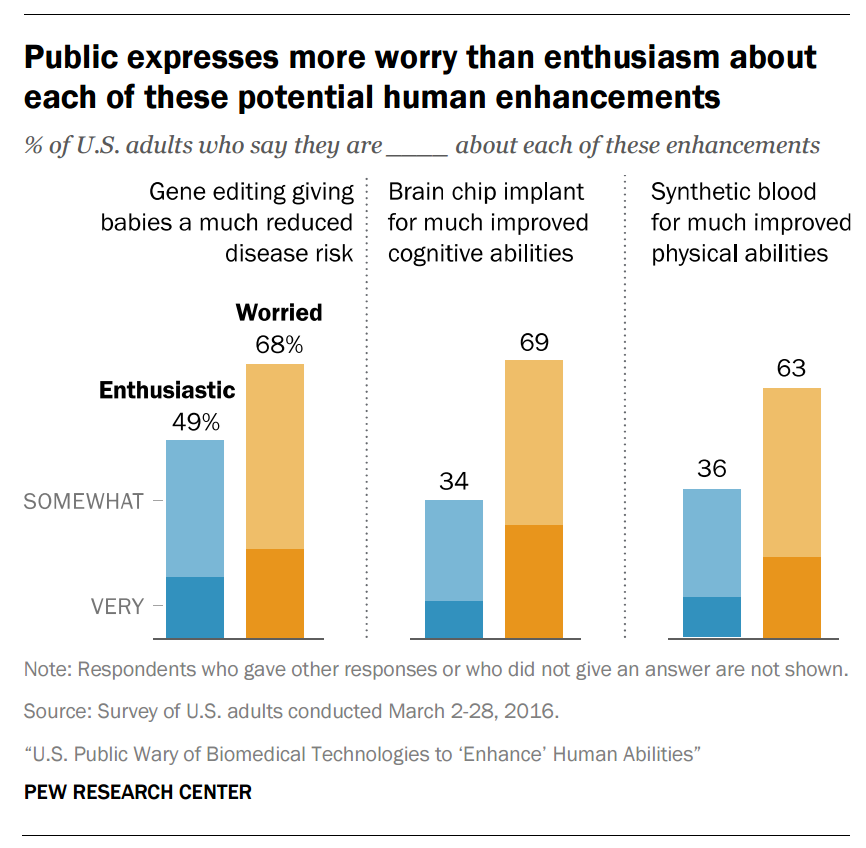

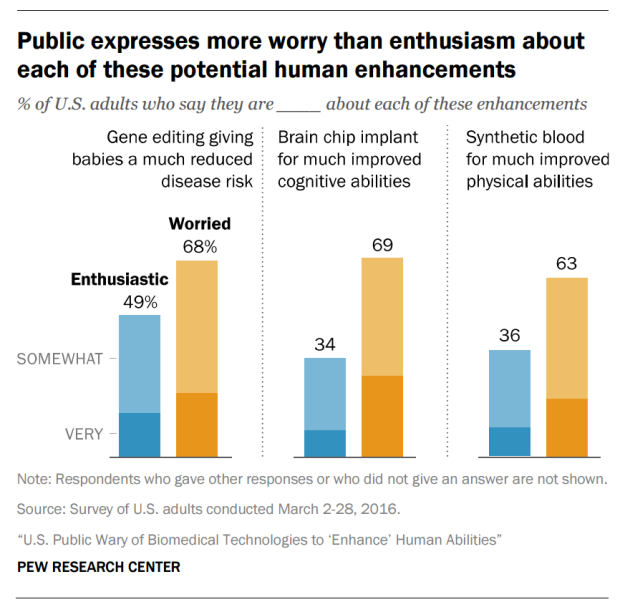

A new survey from the Pew Research Center asked approximately 4,700 adults what they thought of three potential medical procedures that could improve human life. For each, adults were more worried than enthusiastic.

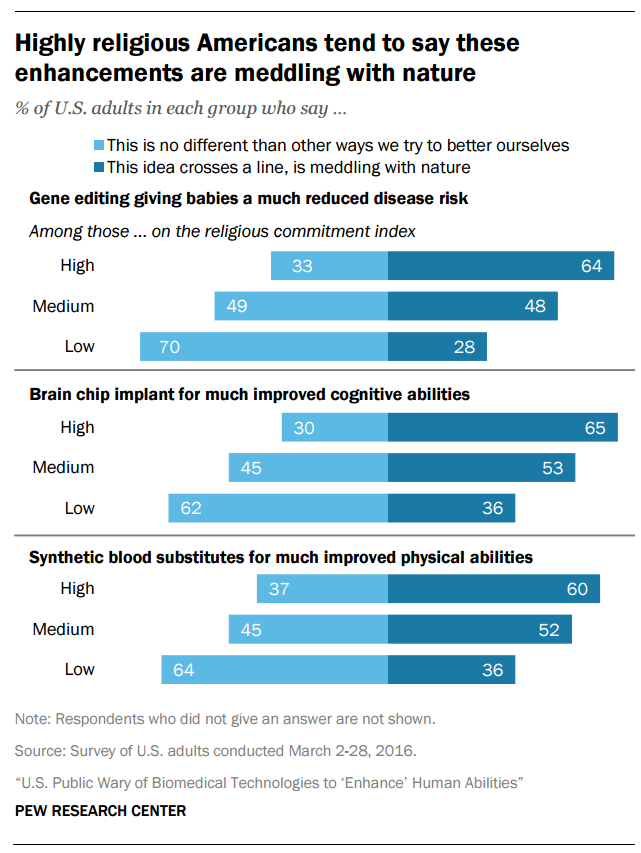

Religious Americans were especially concerned—in fact, the more religious they are, the more concerned they were.

“All of the Abrahamic faiths—Judaism, Christianity and Islam—share the belief that men and women have been created, to some extent, in God’s image,” wrote David Masci in an accompanying essay. “According to many theologians, the idea that human beings in certain ways mirror God make some, but not all, religious denominations within this broad set of connected traditions wary of using new technologies to enhance or change people, rather than heal or restore them.”

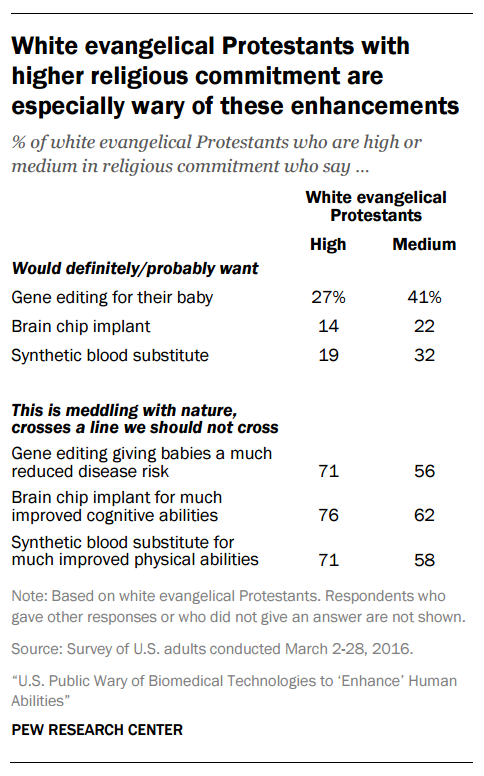

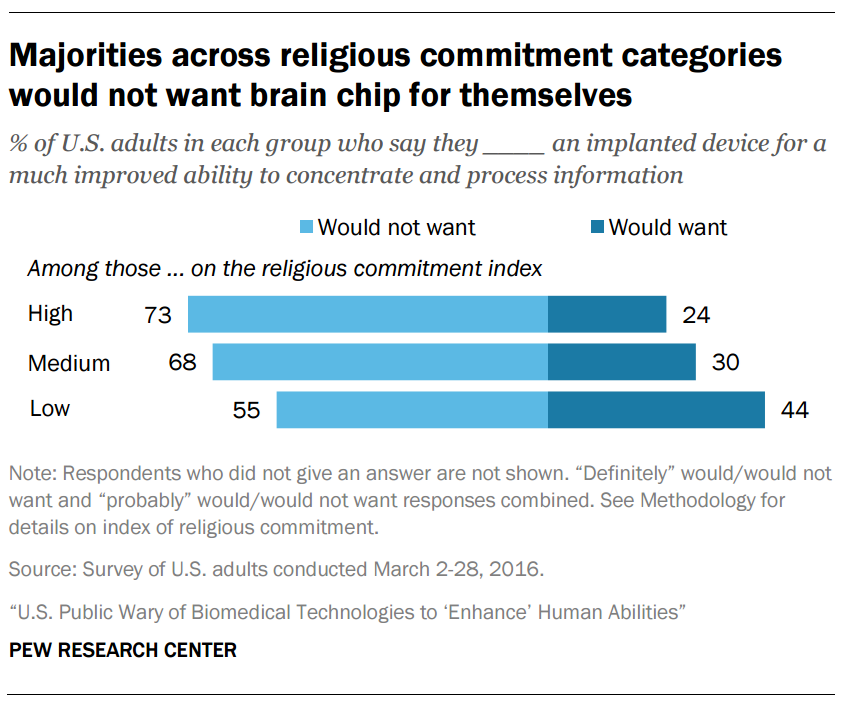

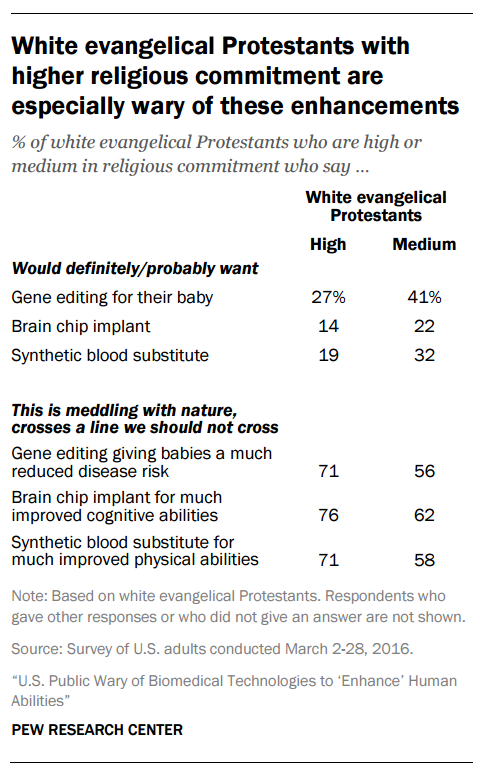

Evangelicals—especially those who say religion is very important in their life, attend church weekly, and pray daily—were the most wary. Those who seldom or never attend church or pray—in other words, those with a low commitment level to their faith—are the least concerned. Those with medium levels of commitment fall in between.

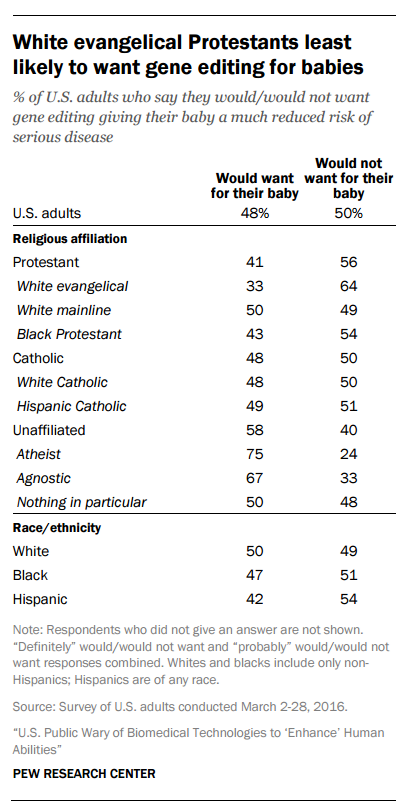

Two-thirds of white evangelicals said gene editing for babies—which could reduce their risk of disease—crosses a line (63%). Half of black Protestants (two-thirds of whom identify as evangelicals, according to Pew) said the same (50%).

While about the same percentage of black Protestants (15%) and white evangelicals (16%) thought gene editing was morally acceptable, far more white evangelicals (44%) than black Protestants (28%) said that it was morally unacceptable. More black Protestants (54%, compared to 38%) were unsure.

Black Protestants were also more likely than white evangelicals to want gene editing for their baby (43%, compared to 33%). They were also more likely to say that gene editing is “no different than other ways we try to better ourselves” (47%, compared to 32%).

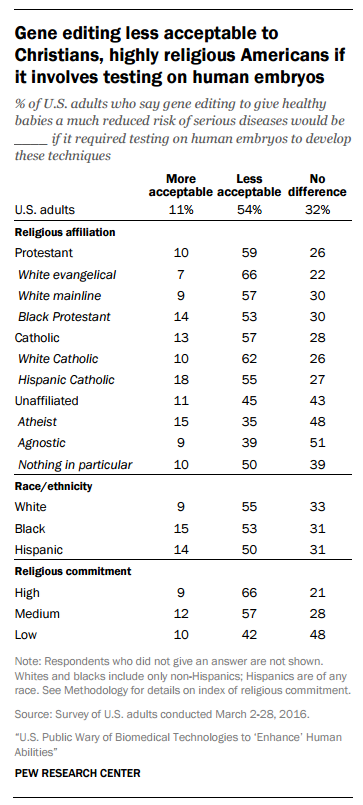

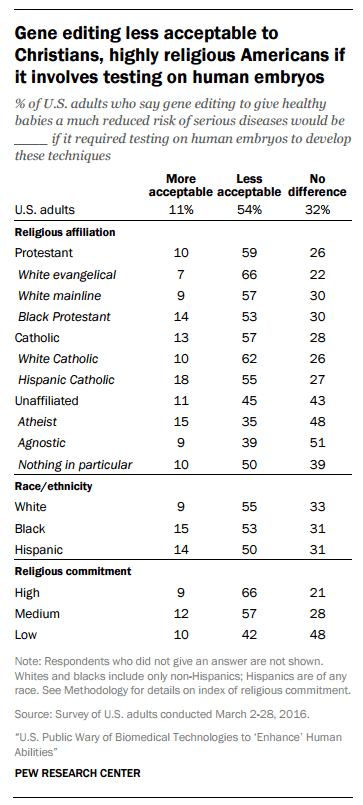

Not surprisingly, most white evangelicals (66%) and black Protestants (53%) said that gene editing would be even less acceptable if it involved testing on human embryos.

A third of those who found gene editing in babies morally unacceptable referenced their aversion to changing God’s plan (34%), while another quarter said disrupting nature is a line that should not be crossed (26%). Other reasons for abstaining from gene editing: it could be controlled or used for wrong motives (9%), it could have unintended consequences (8%), or it isn’t necessary (5%).

Of the 28 percent of adults who said gene editing is morally acceptable, 5 percent said it was because God gave us the brains and tools to do so.

Evangelicals are also skeptical about brain implants to improve function. Currently, cochlear implants are used by those who are have trouble hearing, and brain implants help with motor control in patients with Parkinson’s. But Pew’s question was a little different: asking if people approve of brain implants in healthy people to improve concentration.

Americans in general are more worried (69%) than enthusiastic (36%) about that, and evangelicals are no different. Most white evangelicals (79%) and black Protestants (69%) said they would not want such a device implanted in themselves. Again, the more religious a person is, the more likely they are to oppose such measures.

White evangelicals were more likely than black Protestants to say that implanting computer chips in the brain crosses a line (69%, compared to 51%), as well as more likely to say that it is morally unacceptable (50%, compared to 38%).

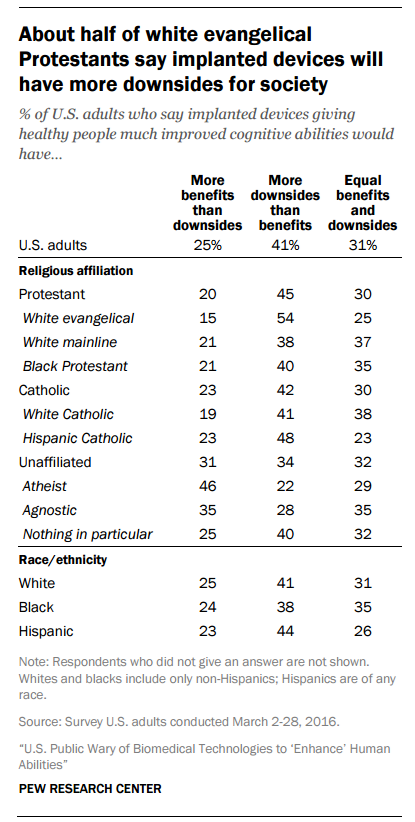

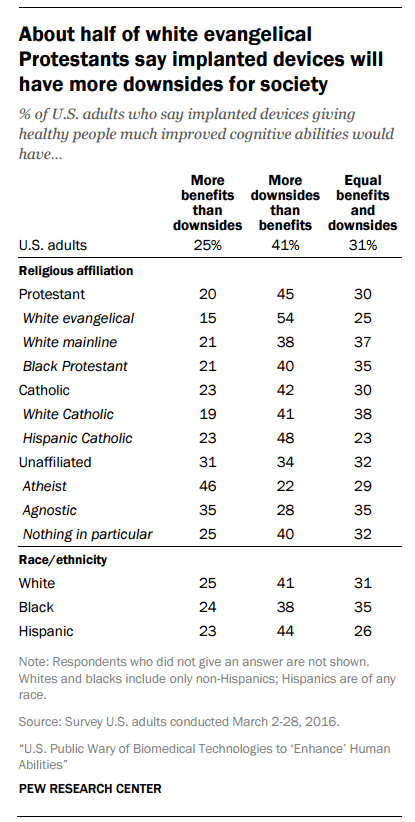

Though black Protestants tracked more or less with the general population in believing that there were more downsides than benefits to chip implants for healthy people (40% of black Protestants, compared to of 41% of the general population), white evangelicals were more likely to think the cons outweighed the pros (54%) rather than the other way around (15%).

Of the nearly 4 in 10 adults who said brain chip implants are morally unacceptable (37%), one-fifth said they thought it messed with God’s plan or signaled the mark of the beast (21%). Others said it disrupted nature (19%), could be used for wrong motives (17%), was unnecessary (13%), or would provide an unfair advantage to those who could afford it (10%).

Less than one percent of those who said brain chip implants are morally acceptable reasoned that implants were permissible because God gave humans the means and brains to innovate.

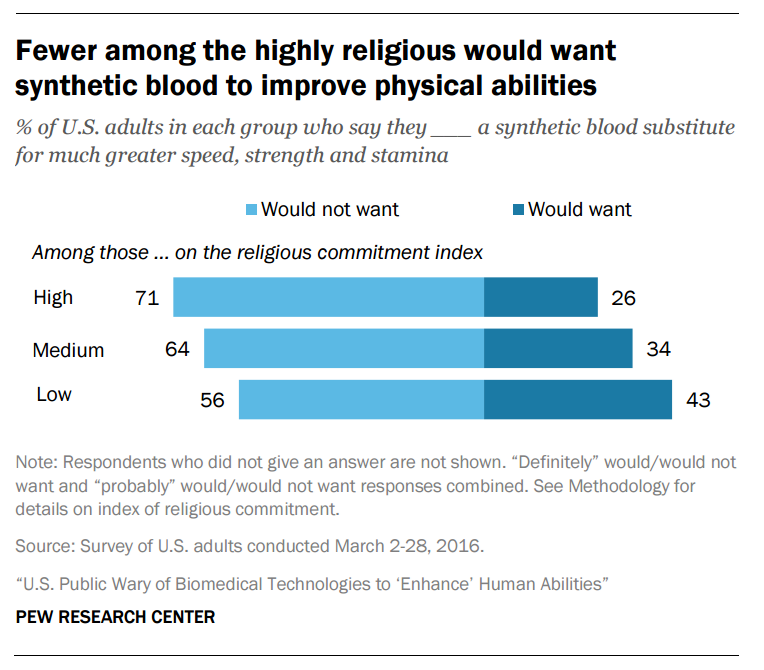

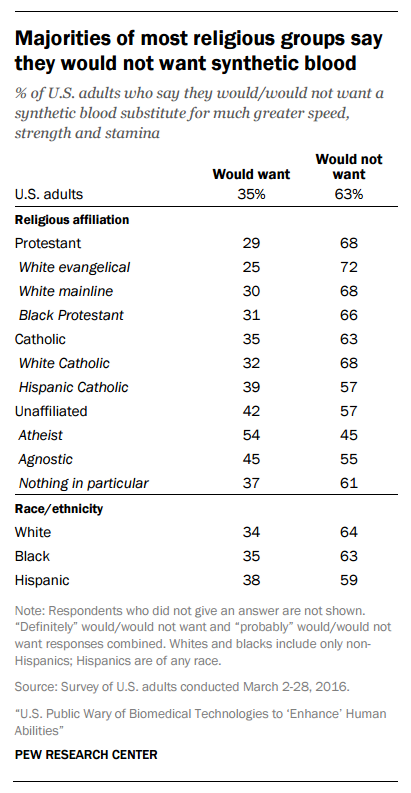

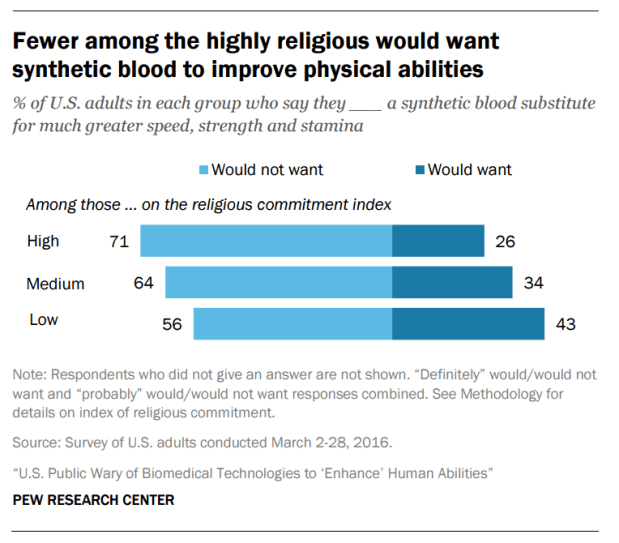

Finally, Pew asked about synthetic blood—a scientific possibility that could carry more oxygen to muscles, resulting in more physical speed, strength, and stamina. Continuing the pattern, this “super blood” was most resisted by the most religious.

White evangelicals (72%) and black Protestants (66%) were more likely than the average American (63%) to say they would not want the “super blood.”

While black Protestants mirrored the US population at large in being evenly split over whether synthetic blood crosses a line (48%) or is no different than other ways we try to better ourselves (49%), white evangelicals were much more likely to say it crosses a line (65%).

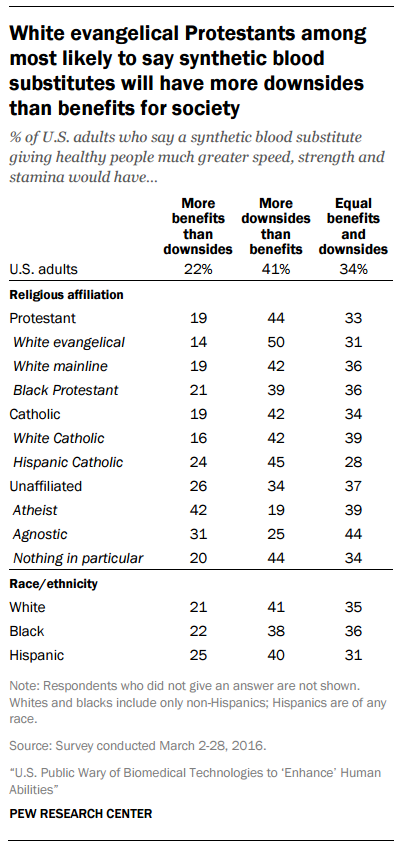

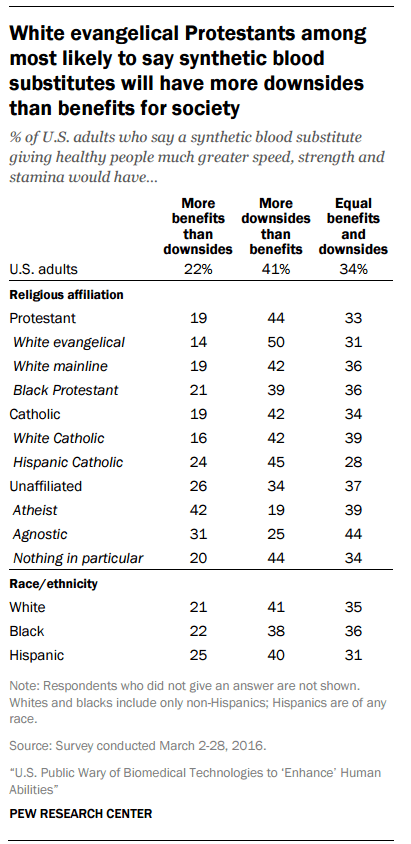

White evangelicals were also more likely (46%) than black Protestants (30%) and the general population (35%) to call synthetic blood morally unacceptable. They were more likely (50%) to believe there are more downsides than benefits to creating blood substitutes than black Protestants (39%).

Of the one-third of adults (35%) who called synthetic blood morally wrong, one in five said this was because it changed God’s plan for us (20%), while a quarter said it was disrupting nature (25%) or unnecessary, especially for healthy people (17%).

About three percent of those who said synthetic blood was morally okay reasoned that God gave us the ability to innovate in order to improve our physical condition.

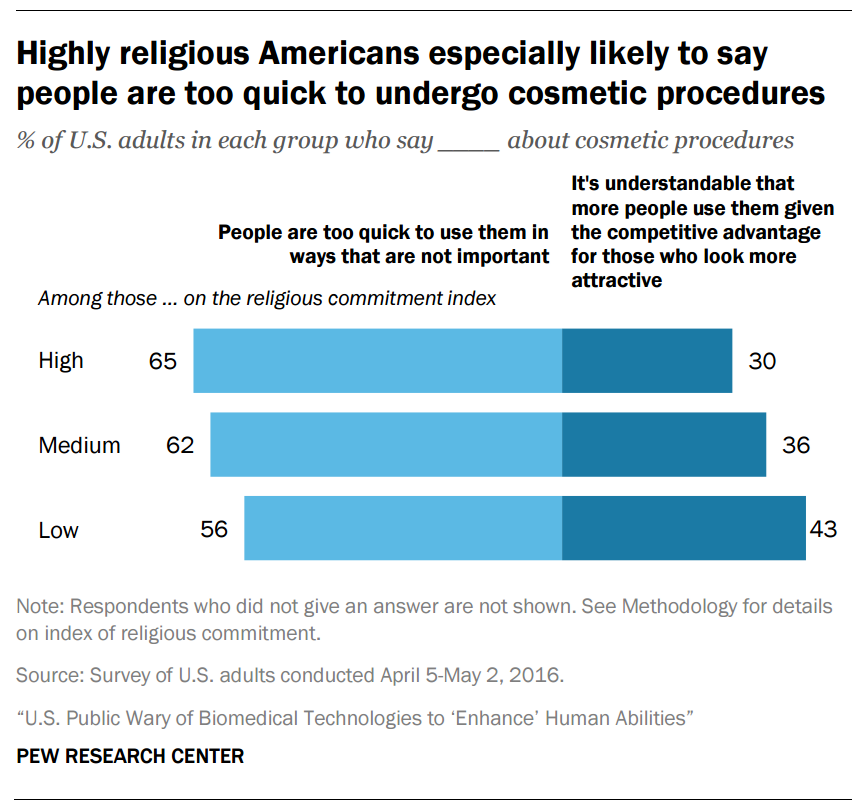

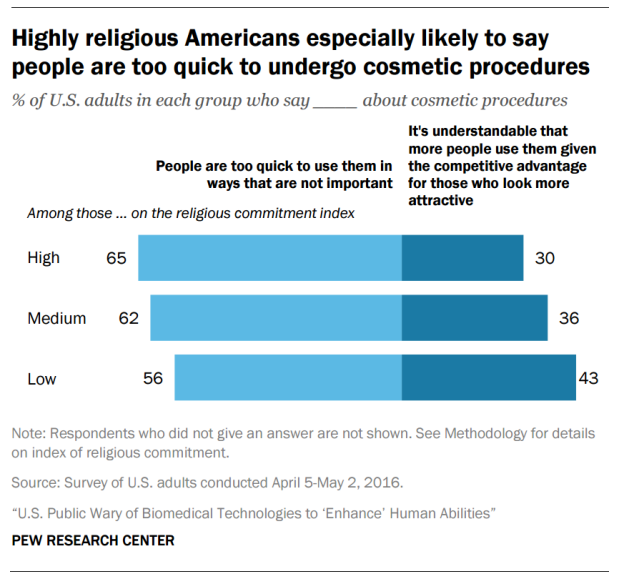

Pew also asked about current physical enhancement procedures, from laser eye surgery to teeth whitening to vasectomies. Overall, 61 percent of adults thought people were too quick to use these procedures in ways that were not important. Highly religious people were more opposed than most.

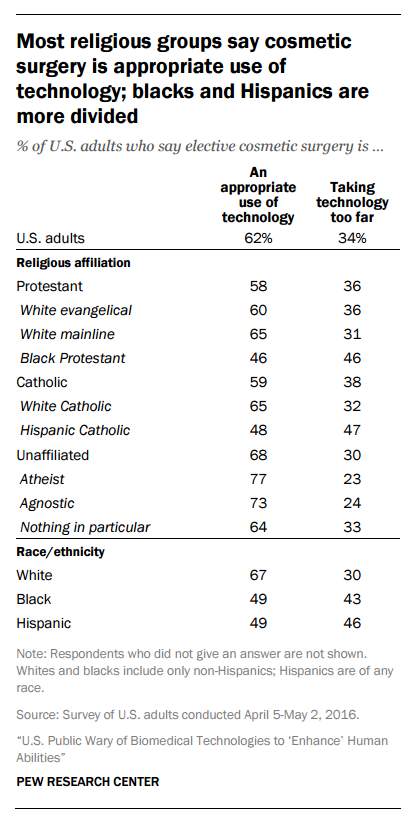

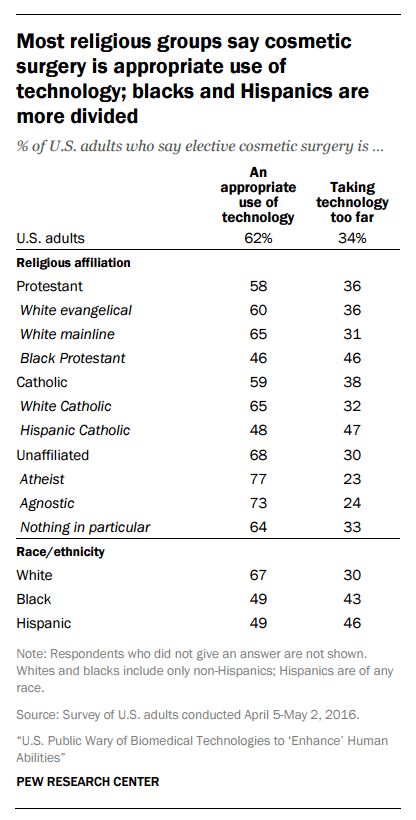

In a surprising reversal, white evangelicals were more likely than black Protestants to believe that current elective cosmetic surgery is an appropriate use of technology (60% vs. 46%). Just one-third of white evangelicals (36%) thought cosmetic enhancements were taking technology too far, compared to 46 percent of black Protestants.

“Conservative evangelical Protestant churches also are likely to be wary of treatments or technologies that enhance, rather than heal, people,” Urbana Theological Seminary professor Todd Daly told Pew. “I think most [evangelical] churches will warn against this. I think a lot of evangelical leaders and pastors will see this as unwise and will call on people to avoid it.”

Evangelicals are wary of playing God, Daly said. “When we attempt to be something more than human, are we running the risk of trying to become, in some ways, like God, as did Adam and Eve? … This is an important issue for Christians that, I think, will help drive the debate for us.”

Pew also referenced Southern Baptist Theological Seminary president Albert Mohler, who called elective genetic enhancement “a new form of eugenic ideology” in a 2005 blog post.

The connection between religious commitment levels and wariness of enhancements was one of the patterns the survey found. Another one: people are less open to enhancements if it is permanent and cannot be reversed.

And although opinions look pretty much the same across racial and ethnic groups, education, income level, age, and gender makes a difference. “Women are consistently more wary than men,” Pew reported.