I might never have become concerned about the physical, emotional, and spiritual condition of people leaving prison had not a long-time friend of mine made it his personal mission to drive me crazy.

With unrelenting persistence, Jim called me week after week for at least six months, describing the latest meeting of a local evening program known as Radical Time Out (RTO).

He was particularly enthusiastic about the evangelistic exploits of RTO’s founder—and, it seemed, force of nature—Manny Mill. (In this article I will follow the universal practice at RTO, rooted in its powerful sense of family, of calling one another by first names.) Born in Cuba, Manny had fallen victim to his mother’s passionate prayers and accepted Christ in Caracas, Venezuela, while running from the FBI on charges of interstate transportation of stolen property. Now, Jim told me, he was a champion for Christ, redemption, and justice—not just for offenders, but for those on all sides of the courtroom.

Whether it was the movement of the Spirit or my selfish desire to get my friend Jim off my back (and off my phone), I joined him at RTO on a Thursday night in October 2013. I’ve been attending ever since.

What began as a Bible study attended by eight men has become an ever-expanding, ever-more-diverse community that now numbers over 100 one-time murderers, rapists, thieves, substance abusers, and gangbangers. Alongside them are mothers, sisters, and fathers whose family members are behind bars—some for life. And to round things out, there are some run-of-the-mill sinners like me—whose media-driven stereotypes of “ex-felons” have been blown to bits.

They come for support and a place where they will not be judged. Their sins are very real (just ask them!), but behind the criminal convictions are men and women in need of a Savior—people who have found him and been found by him.

RTO is a family gathering, complete with dinner, testimonies, prayer, ice cream, praise and worship, and lots of tears and hugs.

Then there’s Manny’s “salsified” brand of gospel preaching, punctuated by outbursts of expressive prayer. Manny’s jubilant blending of Spanish and English can, at times, leave his attentive hearers momentarily bewildered, but invariably the Spirit’s own translation of the one-hour-plus message leaves everyone in the room eager for more. Indeed, no one in the church gym where this weekly family celebration is held ever seems to have his or her fill of God’s Word. Or God’s amazing grace.

“All are welcome,” says Manny every Thursday night. “No matter your crime, color, culture, class, or crisis.”

Increasing in Love

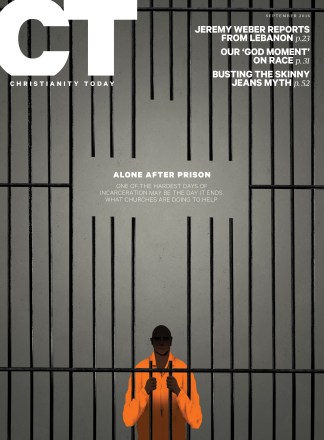

The all-inclusive nature of RTO presents a challenge—and a model—for all churches as they seek to obey the biblical mandate: “Continue to remember those in prison as if you were together with them in prison, and those who are mistreated as if you yourselves were suffering” (Heb. 13:3).

Perhaps never before in our history has that mandate been more crucial.

In 2014, the National Employment Law Project found that approximately 70 million Americans—roughly one in every four adults—have a criminal record that “could compromise their ability to get a job.”

Let alone, I would add, their ability to fully engage in or become a member of a church.

“It’s hard for church leadership and church volunteers to willingly take on known at-risk people when the societal norm is to be risk-averse,” said Lynnea Martin, one of RTO’s “fill-in” Bible teachers when Manny is traveling to area prisons. “Working side by side with someone who has been convicted of a crime and served time in jail or prison can be scary. Churchgoers may wonder if it is safe for them to interact with an ex-offender, especially if they don’t know what crime they were convicted of.”

I witnessed this fear firsthand with one of my first connections at RTO—a man I’ll call Joe—who was convicted a decade earlier for a sex crime. Now branded for life by the state as a “sex offender,” Joe has nevertheless experienced God’s grace upon grace, and has been walking faithfully in Christ since his last conviction.

Joe has also become a family friend. As my friend, he shared his intense interest in becoming a member of a local church. He clearly understood the need (and biblical mandate) to align himself with a group of believers for his own spiritual health and strength.

That God-directed desire began an odyssey that lasted 18 months—from his initial interview (where he shared his story with all its pain and grace) to receiving the right hand of fellowship. And while I rejoiced with Joe when he finally was welcomed into membership, I was troubled by the circuitous nature of the process.

Keeping children safe is, of course, a first priority for church leaders—not to mention the need to follow state ordinances about sex felons in public places. But at times it seemed like state ordinances and church policies also ruled out extending grace.

If we do not welcome the prisoner, or anyone else who is a sinner in need of the grace found in Jesus, we are resisting the Holy Spirit,” says Marco David, pastor of Midwest Bible Church in Chicago. “At the root of our fear is a lack of our abounding in Christ’s love. Love conquers all, including fear. Love compels us to take risks, to show compassion, and to extend grace to the undeserving and the unloved. If our love is not extended to the ex-offender, we are more like a social club than a church. We must increase in love. We must pray radically to love radically.”

Pastor Marco recently started his own church-sponsored edition of RTO.

Messy Ministry

It is the tangible outworking of Christ’s love that heightens my own level of expectancy every time I make it to an RTO meeting. Paul’s declaration that “love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things” (1 Cor. 13:7, ESV) is patiently modeled every Thursday night.

“The hardest part of working with ex-offenders,” says RTO sponsor Chuck Martin, “is to be patient enough to understand who they are and where they are in life at the time they enter our care. Each one is different and usually comes with a lot of baggage. We need to know how to love them while being wise in all of those interactions.”

I learned this lesson after coming to the aid of a recently released man who had been convicted of a felony for assaulting a coworker. I worked with Chuck to find this fellow housing, a job, and cash for essentials.

He claimed Christ was his Lord, and he had memorized a great deal of Scripture. But it wasn’t long before his anger management turned to mismanagement, and he was off to prison again. In the subsequent months, I have lost track of him.

There are few quick payoffs in this messy work.

There are few quick payoffs in this messy work. You need a fellowship of believers, or a committed congregation, to work together, helping one another avoid burnout and cynicism.

“With ex-offenders you are forced to confront hard issues,” Barbara Mill, Manny’s wife, told me. “Is God really sovereign? Is he really a loving God? Where was he when that young husband murdered his wife and unborn child in front of her 14-year-old sister?” (This is not a hypothetical question, but a real situation that has directly affected RTO.)

“You either walk away because it’s too hard,” Barbara continued, “or you wrestle with the issues. I’ve found out for myself that when we wrestle with God on these issues, we grow in our knowledge of him—and that’s always a win for strengthening the body.”

Barbara’s words reminded me of something I read in another context, from orphan-care advocate Shannon Dingle in CT’s special section The Local Church: “Any ministry done well is going to be messy.”

Indispensable Parts

Not surprisingly, then, RTO’s weekly mixture of celebration, joy, and hope—always with a measure of life’s messiness sprinkled in—regularly reminds us of our total dependence upon God.

For volunteers like me who are quick to wonder how we could ever relate to someone with such a different life, dependence means collaboration and prayer—lots of it—and an ever-growing awareness that we are powerless, on our own, to make a difference. All we can do is allow God’s love to work in and through us.

And for those coming out of prison, dependence means trusting and living fully in that love in obedience to the one who paid their ransom and set them free.

Which brings me to another RTO colleague. I’ll call him Jack.

Jack’s case is still in the courts—the high courts. It has drawn a fair bit of media attention. Throughout the snail’s pace of hearings, Jack has claimed innocence, even saying that he had been told by God that his name would one day be vindicated. So far, indeed, the courts have been on his side.

But Jack’s story is more than an endless series of court dates. It is a story that began in a jail cell four years earlier when, to hear Jack tell it, a light appeared, along with a voice telling him that it was Jesus calling Jack to himself.

From that day—and because state restrictions have prevented Jack from getting a job or returning to school—Jack has spent the bulk of his days studying God’s Word, listening to sermons, and increasingly sharing his story with local churches.

He has become a good friend, and his periodic visits to our home for a meal have resulted in my own faith, and that of my wife, being strangely warmed by the realization that Christ is still very much in the business of changing lives. Even lives laid bare on the front page of the Chicago Tribune.

RTO participants often echo Chuck Colson: Jack is a “living monument” to the transforming power of the gospel.

“Sometimes, even now, when I hear a story of what my husband used to be like,” says Barbara Mill, reflecting on Manny’s run from the law, “I think to myself, ‘Who was that man? I don’t know him at all.’ Then I remember that he is a ‘living monument’—the old is gone, the new has come.”

That kind of evidence of God’s transforming power awaits any church willing to take the risk.

“When we step into a situation, in faith, where we bring absolutely nothing of our own and have to completely rely on the Holy Spirit and God’s Word—that’s when we can fully experience what ‘Christ in me’ really means,” said Chuck Martin. “The long-term benefit to the church is full-scale revival as the body learns to become more and more desperate for Christ on a minute-by-minute basis.

“Does it bother us to join in fellowship with ex-murderers, ex-thieves, and ex-sinners of all kinds?” asks my friend Joe, the convicted sex offender mentioned earlier. “If so, then how can we belong to the one who welcomed Paul the apostle, the thief on the cross, and Mary Magdalene into his holy kingdom?”

Is the body of Christ stronger when some of its parts are removed? “On the contrary,” Paul said in 1 Corinthians 12, “those parts of the body that seem to be weaker are indispensable.”

In our region, RTO is on the leading edge of helping the church welcome back those missing members of the body—and as we do so, we discover that the experience has become indispensable for our faith.

“Someone said the reason we don’t experience God doing anything unusual is because we don’t do anything to demand it,” Pastor Marco told me. “When we step out in faith and love to extend grace to the prisoner, we are joining with Jesus in his radical work of redemption. When we go where Jesus is working, we will encounter his transforming presence and power in ways that will fuel our faith and bring glory to his name.”

Harold B. Smith is President and CEO of Christianity Today.