Our age is characterized by what psychotherapist Joseph Burgo called an “anti-shame zeitgeist.” The beloved researcher Brené Brown wrote two No. 1 New York Times bestsellers decrying shame, and her TED Talk, “The Power of Vulnerability,” has been watched more than 26 million times.

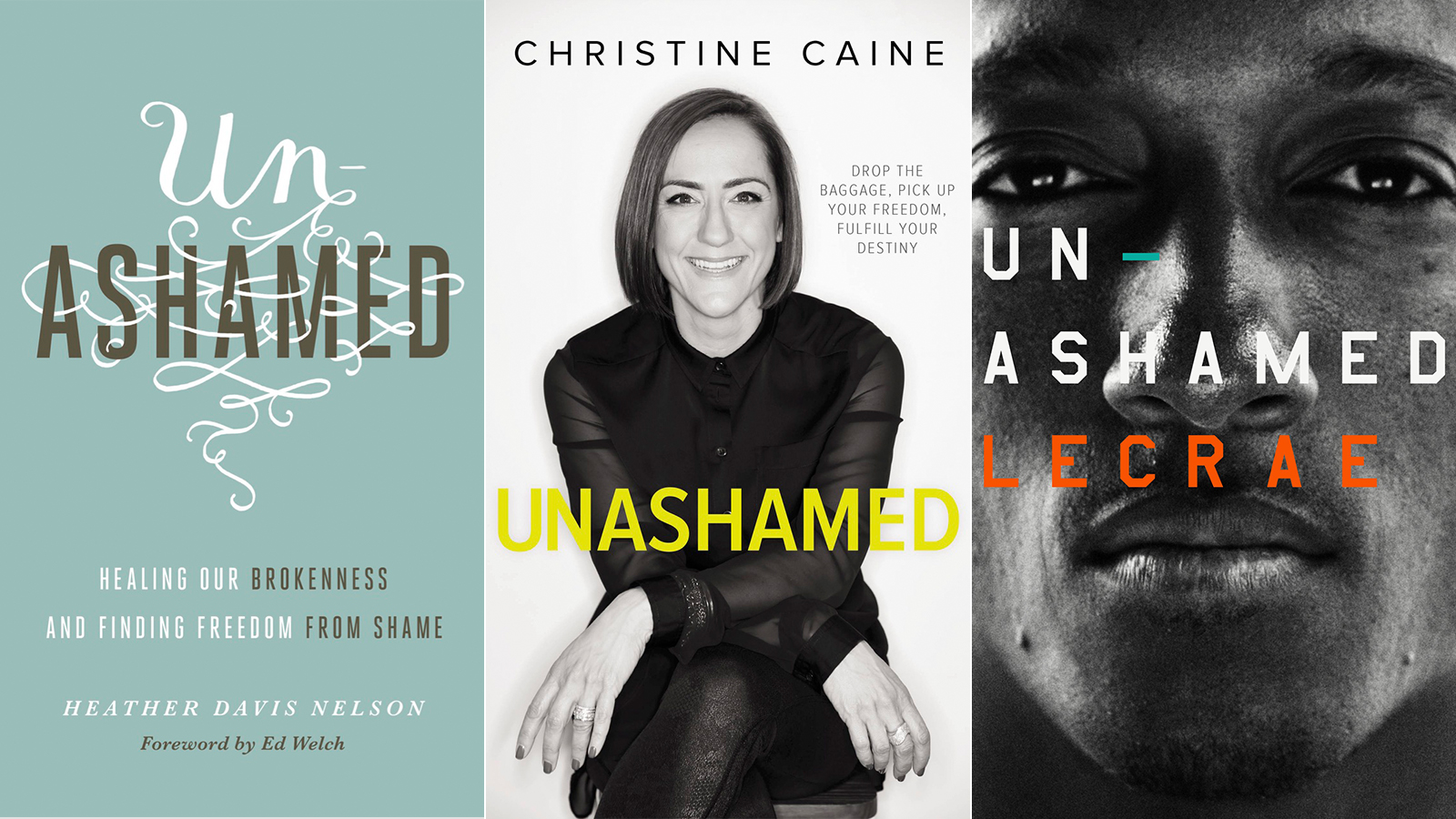

This year, the anti-shame revolution is front and center in Christian publishing, with three new Christian books all titled Unashamed. Go to your local Christian bookstore and ask for a copy of Unashamed, and you may hear, “Which one? Lecrae, Heather Davis Nelson, or Christine Caine? Take your pick.”

There is no shame in sharing a title, but this coincidence points to a marketing reality: becoming proudly unashamed is all the rage now.

Lecrae’s Unashamed is a memoir, and as a fan of his music, I couldn’t put it down. (My six-year-old’s most requested musical artists are Elsa and Lecrae.) Lecrae’s story is compelling and deals with different facets of shame. As a young boy, he confronted deep shame over his father’s abandonment; he also faced sexual abuse. Throughout the book, he returns to the theme of not quite fitting in—whether it be because he was an arty kid in a rough neighborhood or because he is now a successful Christian rapper who neither fits neatly into mainstream Christian music nor mainstream rap.

Caine’s Unashamed follows the Australian teacher and speaker’s two previous titles, Undaunted and Unstoppable. Her women’s ministry, Propel, also lists more than a dozen “un” terms to describe the woman they hope to encourage, including unashamed: “She does not minimize or hide who God has made her to be.” Caine’s book is not a memoir—it’s about how to, as her subtitle states, “drop the baggage” of shame—but she draws heavily on her life story. Like Lecrae, she faced abuse as a child and derision over her ethnic heritage.

Similar to Caine, Nelson’s focus is on how to be free and healed from shame. Nelson, a counselor who graduated from Westminster Theological Seminary, draws explicitly from Brené Brown’s work on shame, but wants to “put [Brown’s] work into a biblical framework,” which she does helpfully. Beyond Brown’s solutions—empathy and vulnerability—Nelson points to union with Christ as an antidote to shame.

We could assume this trio of books represents another effort by Christians to speak into whatever issue or topic has become popular in our present culture. Shame has become a common enemy in Western culture, and we see ridding our lives of shame as part of our quest to embrace our true, authentic selves. But Christian authors have the opportunity to recover more about this in-vogue emotion. The Bible and the history of our faith reveal a varied landscape of shame, with a great deal of room for different types of shame and different ways it can function in lives of individuals and communities. And though liberation from shame is central to the Christian faith (1 Peter 2:6 tells us that “the one who trusts in him will never be put to shame”), Scripture does not seem to reject shame altogether.

Shame and the Self

Most us tend to think of shame as an internal feeling about our self-worth, an understanding closely tied to Western individualism. In his Christianity Today cover story “A Return to Shame,” Andy Crouch explains, “Poignantly described by psychologists and authors like Dan Allender and Brené Brown, shame in this context describes an inner sense of unworthiness, often rooted in trauma and embarrassing experiences. Though real, this sort of shame is psychological and deeply interior.”

The evangelists of the anti-shame movement make a distinction between guilt and shame, as both Nelson and Caine do in their books. They reference Brown’s distinction that guilt says, “I’ve done something bad,” while shame says, “I am bad.” Guilt can be a necessary response to hurting others and other kinds of moral failure. In this framework, when we talk about sin, we refer to guilt—not shame. By this definition, shame is not related to what we do but who we are. Shame is a sense that we are fundamentally wrong, blighted, and bad.

If a sense of essential worthlessness is our sole definition of shame, then we as Christians must reject shame entirely. We root our identities in the Creator’s declaration that we are “very good,” and we believe in the dignity of all humans as image-bearers of God.

The destructive currents of false shame come up in all three Unashamed books. False shame can come from being a victim of abuse. We have shame about our bodies, whether from body image struggles (as Nelson and Caine describe) or from the sting of discrimination, poverty, or family instability (in Lecrae and Caine’s life stories). Shame can come from violating “norms” of society or stringent perfectionism—Caine struggled with going against cultural and familial expectations when she chose to pursue an education and career.

We can even feel shame about being Christians in the face of hostility, an impulse Scripture calls us away from and Lecrae refers to throughout his book. He writes, “Part of being human—and especially being Christian—means not fitting in, and the only solution is learning to look to God for ultimate recognition.” False shame malforms us and keeps us isolated, hiding, fearful, and unable to believe that God or others love us.

In the broader contemporary conversations swirling about shame, we are quick to dismiss it and encourage each other to overcome this sense of unworthiness, but we rarely explore other aspects of this complex emotion. Historically, including in the Scriptures, shame carried a communal dimension. This conception of shame reveals that it’s an inevitable part of having deep social ties and living in community.

In ancient pre-Christian societies, shame did not have to do with a feeling about our “true selves.” Instead, shame referred to a person’s status or belonging within a greater whole. If a man was courageous in battle, for instance, he would win honor for his kin and tribe, and therefore for himself. If he ran from it, he’d reap shame. One’s flourishing as a person was inconceivable apart from the flourishing of one’s community.

Early Christianity sprang up within this sort of honor/shame culture. Simon Chan points out that the theme of shame is vastly more prevalent than guilt in the Scriptures. While guilt is attested 145 times in the Old Testament and 10 in the New Testament, shame appears 300 times in the Old Testament and 45 in the New. Some scholars point to Paul as the inventor of “the individual,” who freed early Christians from societal hierarchy in Christ (Gal. 3:28) and intergenerational curses. Yet, Christianity largely resists “individualism”—a hyper-focus on our own autonomy and self-construction.

Nelson calls us to participate in the community that “we belong to through Christ,” but within that community, she sees no place for shame. If Paul were to write his own Unashamed, he’d likely write it to the church—a group, as opposed to individuals—and call the community to be liberated from the world’s false standards of honor (like wealth, racial supremacy, body perfection, etc.). At the same time, he would affirm how this community of new creation must follow and emulate Christ with its conduct, lest it bring dishonor to the community and also to the name of Christ. In 1 Corinthians 6, for example, Paul chastises the church for lawsuits among believers, and he explicitly says, “I say this to shame you” (v. 5). Lawsuits among believers bring public shame on the whole community; the church “loses face” in front of unbelievers.

As a community, the church has always required essential standards and boundaries, the violation of which shames those who transgressed them and which create an in/out group. Any group or institution defines itself based on what the community considers a violation of the association. To take a seemingly “non-religious” example, if you are caught cheating in your bowling club, there will be resultant social shame. Think of how Walter’s strict adherence to bowling standards in The Big Lebowski leads him to pull a gun on a friend for a foot fault—“If you mark that frame an ‘eight,’ you’re entering a world of pain.” Walter’s response is funny because of its over-the-top absurdity, but it highlights how any community will unavoidably have standards of honor, the breach of which induces shame.

A More Nuanced Definition

In an article in The Atlantic, Joseph Burgo notes that scientists have observed a biological shame reaction in every culture on Earth and have theorized that humans are “pre-programmed” to experience shame from certain stimuli. He writes:

Evolutionary psychologists and sociobiologists believe that guilt and shame evolved to promote stable social relationships. According to the Oxford Encyclopedia of Evolution, “conformity to cultural values, beliefs, and practices makes behavior predictable and allows for the advent of complex coordination and cooperation.” While the anti-shame zeitgeist views conformity to norms as oppressive, support for a great many of our social norms and the shame that enforces them is virtually unanimous.

The examples he gives are the social opprobrium conferred upon “deadbeat dads” who abandon their kids and refuse to pay child support, or the social outrage we display toward child predators. He argues that shame can “place a brake on behavior destructive to a well-functioning society.”

As Christians, we need a more nuanced definition of shame that acknowledges and resists the destructive aspect of false shame and self-hatred, but that also rejects defining shame solely within the moral framework of what Philip Rieff and Robert Bellah called “therapeutic individualism.” As Bellah noted several decades ago, this sort of “therapeutic attitude denies all forms of obligation and commitment in relationships.” A more nuanced definition of shame is necessary for the flourishing of both individuals and the rich communities necessary for their formation.

There is more than mere semantics at stake here. If we as a church do not learn to discuss shame properly, we will either fall into creating a church culture of destructive shame (as Christian communities have certainly done in the past) or, on the other hand, we will end up endorsing a wholesale moral autonomy and radical individualism.

Understanding shame as solely a negative interior experience of the individual can feed a hyper-individualism that leaves us isolated and, consequently, more prone to unhealthy shame. The primary solution to shame that is offered by many Christians is gospel-focused “self-talk,” and we see this solution in this year’s Unashamed books. We speak “good news” of our belovedness to ourselves, and in some cases, this can start to seem like a more spiritual version of the old SNL Stuart Smalley sketch: “I’m good enough, I’m smart enough, and gosh darn it, people like me.”

But as Andy Crouch reminds us, as helpful as positive self-talk may be, the solution to shame can’t be found in the individual. The remedy to shame is “being incorporated into a community with new, different, and better standards for honor. It’s a community where weakness is not excluded but valued; where honor-seeking and ‘boasting’ of all kinds are repudiated; where servants are raised up to sit at the table with those they once served; where even the ultimate dishonor of the cross is transformed into glory, the ultimate participation in honor.”

This new community, like all human communities, will have standards of honor and shame, but those standards are set by Jesus, which will often result in a radical reversal of our culture’s (often unspoken) honor/shame rules. In this new community, those who mourn and those who are poor in spirit are honored; the outcasts are brought near; and the one who is worshipped is he who “for the joy that was set before him, endured the cross, despising its shame.”

Our own stories and narrative often reflect this complexity around shame, and in his Unashamed, Lecrae ends up offering a more nuanced version of shame through his life story. As he matures, he learns to shed false shame, and yet he writes that after reading the Scriptures one day, he had a powerful spiritual experience: “It was like a blindfold fell off my eyes. I’d been celebrating things I should have been ashamed of, and I had been ashamed of what I should have been celebrating…Surrendering to God was the key to receiving life.”

Unashamed, Not Shameless

There’s nothing wrong with Christians using the term or title “unashamed.” Certainly, the concerns raised by the anti-shame zeitgeist provide an opportunity for Christians to offer our distinctive solution to shame—the shame first birthed in us in the Fall is now covered in Christ. Yet we must also keep in mind that “unashamed” is not a moniker that Christians earlier in our history would have likely adopted. Also, being “unashamed” cannot mean the same thing as being “shameless”: a term always used in Scripture negatively and associated with judgment. In the new kingdom of Christ, there remain standards of community honor, and thus, shame.

Here’s one example: Martin Luther King Jr. called it a “shameful tragedy” that “11 o’clock on Sunday morning is one of the most segregated hours…in Christian America.” Like Paul to the Corinthians, King was shaming white Christians for contradicting the gospel they proclaimed by upholding segregation. White Christians publicly and actively denied the kingship of Christ over this new unified humanity that is the church, the body of Christ.

In this case, white Christians would have been right to be ashamed of their community’s failure. When we confront this continued reality of church segregation today, shame is a proper response, as we are not honoring Christ before the world. The question is not whether we should feel that shame, but what we should do in response to it. In our shame, we can lash out in self-defensiveness or seek to minimize or hide our sin—or we can repent, be humbled, and go to Jesus, not only for forgiveness, but with a plea to make our community reflect the standards of love and honor we are called to as a new creation.

The role of shame in Christian thought is, at the end of the day, simply more complex than a simple definition of shame as “good” or “bad.” Jesus covers our shame, just as God clothed the shame of Adam and Eve in the garden. But he also calls us to repent for our false standards of honor. He incorporates us into a new community, an eternal family and a place of belonging that lives by grace with a new ethic of honor and shame. Recovering this nuanced and historically complex idea of shame will help us better understand the Scriptures, community, the church, and ultimately, ourselves.

Tish Harrison Warren is a priest in the Anglican Church in North America and works with InterVarsity’s Women in the Academy & Professions initiative. She is the author of Liturgy of the Ordinary: Sacred Practices in Everyday Life (IVP, December 2016). More at TishHarrisonWarren.com.