New York Times best-selling author Beth Moore has made recent headlines in The Daily Beast and other media outlets for coming out publicly against sexual assault. “My whole ministry life is serving Jesus through serving women. To expect me not to speak up on their behalf is like expecting a dog not to bark,” she tweeted. Her response to Trump is apolitical, she says. “My tweets … had one purpose: to speak up for sexually abused women who feel voiceless. I do not endorse/support either candidate.”

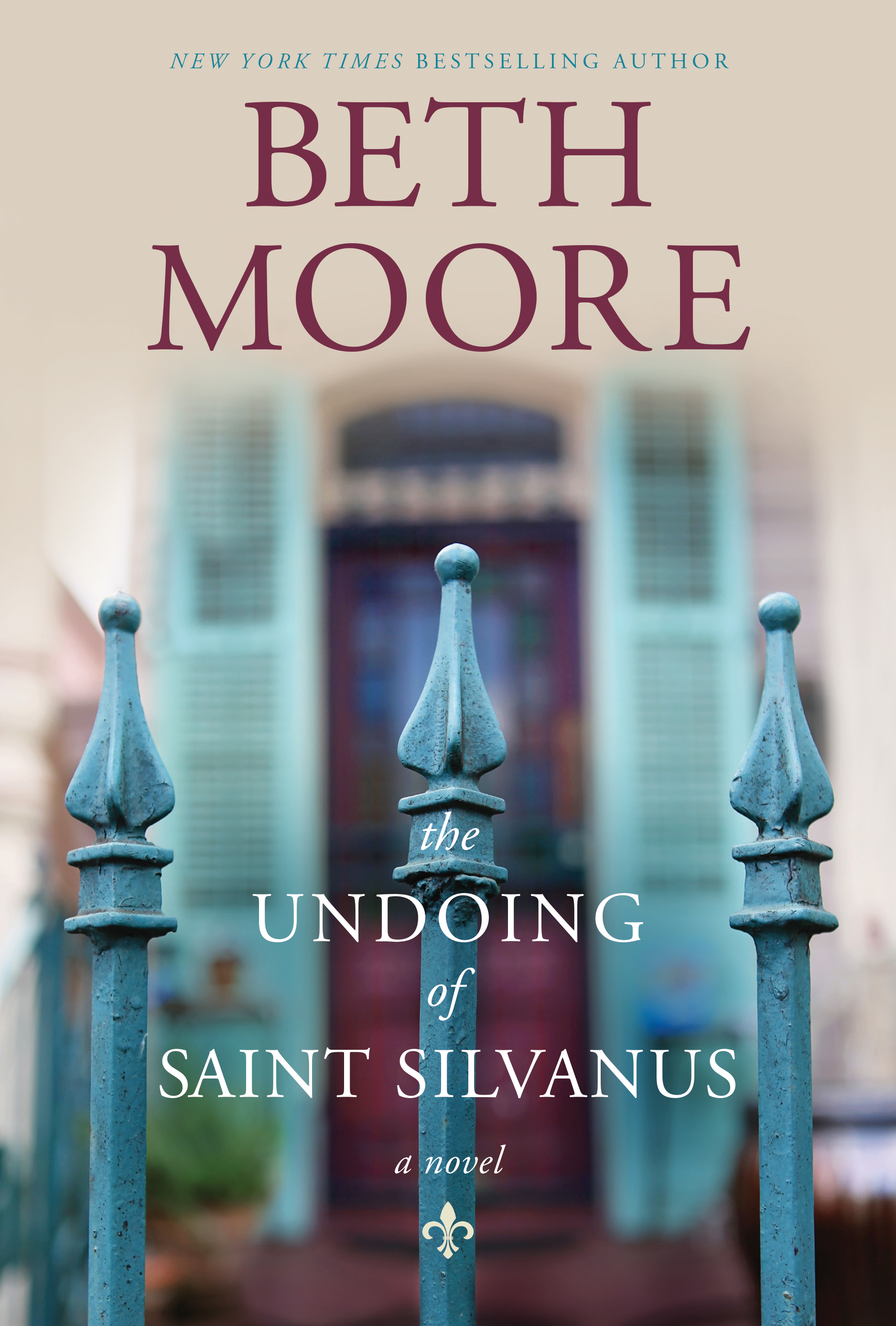

Although Moore’s recent appearance on the political stage is consonant with her mission and ministry, nonetheless, it reveals a new side to someone that most of us know only as a public speaker and Bible study author. In her writing life, Moore is once again breaking new ground by debuting her first work of fiction: The Undoing of Saint Silvanus. The story follows a protagonist named Jillian Slater who is forced to face her painful past after her father drinks himself to death.

I spoke recently with Moore about the novel, her motivation for writing it, and how God shows up in the dark spaces of our lives.

You mentioned that this is your “maiden voyage,” your first dive into fiction. You’ve worked on this for so long, how does it feel to finally have this novel out in the world?

I’ve been on the book tour this week and heard myself being introduced—sitting there on a radio program, I can hear them introducing me and saying I have a new novel out—and I keep thinking, “That can’t be me! That cannot be me.”

It was about three and a half years [of writing the book] because I was doing it on the side while writing the Bible studies. So I finished one Bible study and wrote two others through the course of writing this novel. It took me forever to tell anyone. I told one person. I did not tell my family because I thought it would probably never come to fruition anyway. I certainly didn’t say anything publicly. But it has been nerve-wracking in a way the other projects were not. Although, it’s nerve-wracking every time because it’s very, very, very vulnerable to publish a book.

Right, it’s like your baby has gone out there.

When you do fiction, it is your imagination you have put out there. And I think people will find that the book is grittier than they expected it to be because I told a couple of people, “If I could have just written the way I wanted to, I would’ve done something like Jan Karon. I love how she writes. I love the Mitford series. But you know, Mitford … my life wasn’t Mitford.” There was nothing about my life that vaguely resembled Mitford and so in a sense, I still have to be true in fiction.

How was your process different from nonfiction to fiction?

Part of it I did get to research. For instance, I had to picture the inside of the apartment house [depicted in the story]. I furnished the whole thing by looking for antiques online and printing out pictures and looking in magazines. I even did the landscaping. I had a big fat notebook. This is the kind of stuff I love. I researched what a Methodist church would’ve been like 100 years ago. At the very beginning of it, I literally went to New Orleans, checked myself into a bed and breakfast, and just walked and thought. The history of New Orleans was always a fascination to me—such a blend of light and darkness and plague and pleasure and hedonism and fear and death. It’s just a very, very intriguing city. I have this strange love relationship with it.

I’ve been asked a number of times, “Did you know where it was going to go? Did you know what the story would be?” Absolutely not. I first pictured the place. I got the idea for this residence, and then everything went around it as I wrote it. So I never knew at any time where it was going to go. The first time I knew it was going to finish was when I was again on a walk in the country, and I realized what the last chapter could be. I thought, Okay. There’s no way God would let that stir around in my heart if it didn’t have an intended finish. Let’s do it.

How exactly did you come up with a story that centers on family dysfunction and alcoholism? Is there something in your life that inspired you? For one thing, I love complex people. I am intrigued by complicated relationships and how those dynamics work. And in that respect, the book is wholly reflective of my own past and my own experience. My parents were complicated people. They had a complicated relationship. My home was very, very complicated. I hope that comes across in the book as not all bad, but just a complete cocktail of sweet and salty, the good and the bad and the ugly all under one roof. It was just pretty messy. So that part of the story is very true to my own experience.

As far as alcoholism and the ramifications of that—the way that lives are stolen by severe addiction—you pass by somebody on the street asleep, and you just think they’re these nameless skeletons that somehow still draw breath. Those are people known by God. They have a story; we just may never know it. One of the insights I hope readers have at the end of the novel is that there truly is no “John Doe.” My life has intersected with homelessness, and the book presents a view into that world that I hope says, “Those people have names. They have birthdays. They had hopes. They did not dream of sleeping on the concrete. It never occurred to them growing up.”

In the last part of your book, in a letter to your readers, you wrote, “I’d like to have been a person who could write a lighter story than what you found in these pages.” Were there any ways telling the story impacted you personally or maybe connected some dots for you?

I have had really deep valleys in my family of origin and tremendous difficulties that haunt our family to this day. And then in my own family unit with Keith [my husband] and our girls, we’ve had tremendous challenges, but at the same time, we have laughed our heads off and had extravagant joys. So I hope the reader finds all of that in the story. Yes, it starts heavy from page one. When I first turned it in, my friend Karen at Tyndale was like, “If you would’ve told me five years ago I would open up a novel from you and this would be the opening page, I never would have believed you.” But what I hope is that it also provides laughter, because that’s also very true to my life. In fact, [my daughters] Amanda, Melissa, and I continually say that the more absurd life is in that present season, the harder we get tickled for some reason. As my brother says, we have a strong grasp of the absurdities of life. And so I hope that’s also reflected in the book.

In The Undoing of Saint Silvanus, you explore some of the same themes you explore in Breaking Free. Do you think fiction can deliver this message in a way that nonfiction can’t?

Several years ago, I had this real moment with God when he made it very clear to me, “Now, you are about to go off-road to anywhere I send you.” Not in words of course, but in my heart and through Scripture I heard, “Fences are gonna go down, and I’m gonna send you places that you have never been and you would not have dreamed of going.”

And so I really believe this is characteristic of what he was doing with the fiction project. It happened today at a book signing at Barnes and Noble. One of my colleagues at Tyndale was watching over the line and got talking to a woman who was from Korea and was not a believer, but she was intrigued by what was going on in the line and these dynamics as the women and I were greeting one another, because there were many hugs and such laughter. I was signing the book, and she began asking about it. She said, “Well, I’m open.” Of course, I hope she reads it, because it’s a different genre with the same goal: Jesus is not like anyone else you will ever meet. He cannot betray you. He cannot reject you. He has no dark side, and for someone with my background, that’s one of the most important things you’ll learn about him. You won’t find out he’s this authority figure you thought you could trust but you find out in the dark that he is somehow perverse and mean-spirited. This is Jesus—pure and lovely and holy and the absolute embodiment of perfection.

You mentioned a little bit about the homeless and realizing there are no “John Does.” Is there anything else you hope readers walk with as they close the book?

I hope so much that someone will shut the book and dare to pray about someone they have not spoken to, dare to get down on his or her face before God and say, “I’m asking you for miracles. I’m asking you to do miracles of reconciliation. I don’t know how. I’ve tried everything. I know I can’t force this, but God, in your mercy, would you please …”

When someone does not want what God has to offer, he is not going to force it on them. But can God reconcile the irreconcilable? Yes! The only reason I still have a marriage is because he can. The only reason I have some of the relationships that I do from my past is because he can.

I just want to say to somebody, “He can work miracles in your family!” It starts with you. Just one person. And that one person who seeks health and wholeness in Jesus has to be willing to be misunderstood by the rest of the family and maybe even despised even more. It’s not just deceit that is contagious in a family; it is not just sickness that is contagious in a family; it is also wellness. It is also joy. It is also faith. That is what I hope they shut the book with. All things are possible.

To sign up for a free book club webcast hosted by Beth Moore on January 20, during which she will discuss her debut novel live from New Orleans, please visit bethmoorenovel.com.