When I began work on A Prophet With Honor: The Billy Graham Story back in 1986, I made a list of people I wanted to interview. I asked, “How many of these are still alive and how many are still with the ministry?” The answer: “They are all still alive and they are all still with the ministry.” That wasn’t exactly true, but it was remarkably close. Nearly all the men who started out with Billy Graham in the 1940s were still with him 40 years later, and most of the “newcomers” had been with him for at least a quarter century.

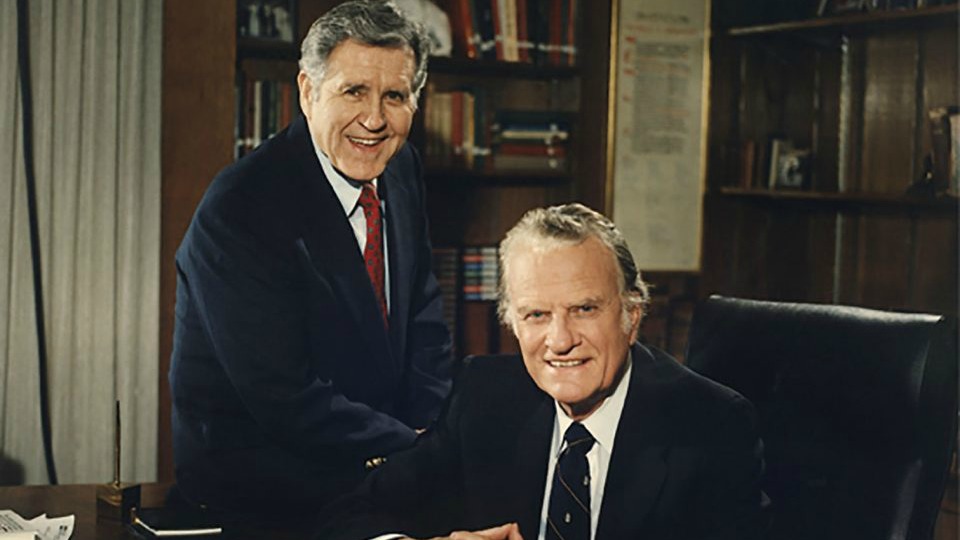

I have since watched the inevitable winnowing of this band of spiritual brothers who held up Graham’s arms over more than seven decades of globe-girdling ministry. Almost all are gone, and the recent death of Cliff Barrows, Graham’s music director, closest friend, and most trusted associate, marks the end of one of the most enduring partnerships in evangelistic history.

The two met in 1945 when Graham, scheduled to speak at a Youth for Christ (YFC) event in Asheville, North Carolina, learned that his regular song leader was not available. Someone suggested he enlist Cliff and Billie Barrows, two young musicians spending their honeymoon in the area. Graham was less than enthusiastic about using an unknown musical team, but he greeted the couple with a smile and said, “No time to be choosy.” The service exceeded expectations and when Graham visited England the next fall for a six-month tour, he invited Cliff and Billie as his musical team.

Barrows joined YFC and enjoyed success not only as a singer and gospel trombonist but also as a gifted evangelist. He intended to continue preaching but accepted the opportunity to assist Graham. Despite their drive, both men possessed amiable, conflict-avoiding spirits, and a genuine appreciation for the other’s abilities. It was during that first trip that, according to Barrows, “God really knit our hearts together in a special way.” Not long afterward, Graham asked Barrows to consider becoming a permanent member of his team.

Barrows recognized that he would probably never quite equal Graham’s success as an evangelist. He also saw that their most notable abilities were complementary rather than competitive; they could accomplish far more together than either could alone or, for that matter, in tandem with anyone else they knew.

One evening in Philadelphia, he and Billie came to Graham’s hotel room to give him their decision. “Bill,” Barrows said, using that address to distinguish his friend from his wife, “God has given us peace in our hearts. As long as you want us to, from now till the Lord returns, or whenever, I’ll be content to be your song leader, carry your bag, go anywhere, do anything you want me to do.”

It was a notable surrender of self, all the more so because it was volunteered rather than demanded. As we visited 40 years later in a nearly empty cafeteria near his home in Greenville, South Carolina, Barrows reflected on the sacrifice of ego he had made and said in a quiet tone, utterly free of dissimulation, “I still have that same peace of mind and heart. I think Bill knows that.”

As music director and stage manager for Graham’s crusades, Barrows appreciated soloists, musical groups, and moving testimonials from celebrities and others, but he always retained his conviction that “the Christian faith is a singing faith, and a good way to express it and share it with others is in community singing.”

He was able to turn hundreds of volunteers into mass choirs and engage tens of thousands in fervent congregational song. For the latter, he typically showed respectful tact by choosing hymns that even those who didn’t attend church often were likely to recognize—“Bless the Lord, O My Soul,” “Amazing Grace,” and “When We All Get to Heaven”—but avoided those that contain such words or phrases as “I worship,” “I adore,” or “I praise your name,” which might embarrass outsiders or make them feel they didn’t belong. Those sentiments were left to the choir or soloists, who presumably could sing them with a clearer conscience.

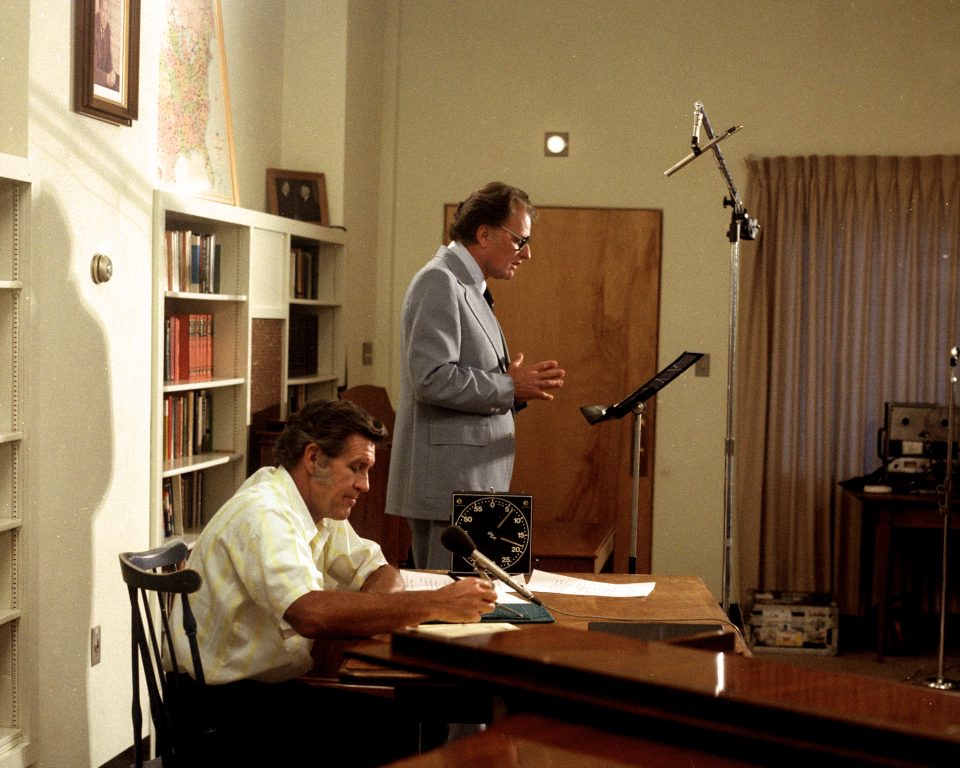

Barrows’s cabin studio

From 1950 until just weeks before his death, Barrows played a key role in the long-running Hour of Decision radio broadcast. At the first broadcast from the Ponce de Leon baseball stadium in Atlanta on November 5, 1950, he announced, “Each week at this time… for you… for the nation… this is the Hour of Decision! And now, as always, a man with God’s message for these crisis days, Billy Graham.” He remained as host of the program until 2014, then served until a few weeks before his death as host of a new digital version, Hour of Decision Online.

The program combined music, taped segments from crusades, and, for many years, a studio sermon from Billy Graham, and listeners might have imagined it was produced in some slick broadcast facility in a major metropolis. In fact, for many years it emanated from a tiny studio in a cabin behind the Barrows’ pleasant but unostentatious home on a hilltop on the edge of Greenville, South Carolina.

Barrows and his late Billy Graham Evangelical Association (BGEA) associate Johnny Lenning built the cabin themselves, and BGEA paid no rental for its use. Barrows paid a yardman out of his own pocket, but he, Lenning, and a secretary handled the janitorial duties themselves. He did not seem to count it remarkable that the most popular religious radio program in history, airing on more than 500 stations at its peak, was put together in a little wooden building in his backyard. “That’s just one of the phases of our job,” he said with a shrug. “A very small part.”

Graham’s go-to guy

No characteristic of Billy Graham’s ministry has stood out more than its stability. While in some evangelical circles vaunting ambition, fragile egos, and naked pride have created chronic tension and high turnover, BGEA was famous for its organizational constancy and internal harmony. It was not without spot or wrinkle, and almost any member of the association could point to minor flaws, but it has been an impressive monument to Billy Graham’s leadership and a remarkable example of effective nontraditional bureaucratic organization.

No one, however, seems to have been more important to the unity of the organization than Cliff Barrows. Several ministry veterans admitted, “Cliff is the guy to go to if there is a real problem.” One key function he served was to discourage power plays on the part of other members of the association. “If anybody could have built a following for himself,” a close associate observed, “it would have been Cliff, because he is such a warm person. But he has not done that. He has been a model for other people in the organization. If the No. 2 man isn’t grabbing for power, it’s harder for anyone else to do it.”

Certainly Graham understood the value of his dearest friend. In a brief but singular tribute, he told the nearly 10,000 evangelists gathered at the International Conference of Itinerant Evangelists in Amsterdam in 1986, “God has given me mighty men, but the mightiest of all has been Cliff Barrows.”

William Martin, senior fellow for religion and public policy at Rice University’s Baker Institute, is the author of A Prophet with Honor: The Billy Graham Story (William Morrow, 1991), from which parts of this article are adapted.