Making a better Bible is harder than it sounds—even if you’re given more than a million dollars to do it.

Adam Lewis Greene, creator of the Kickstarter-funded Bibliotheca, learned the intricacies of the process as about 15,000 supporters waited through two years of production delays.

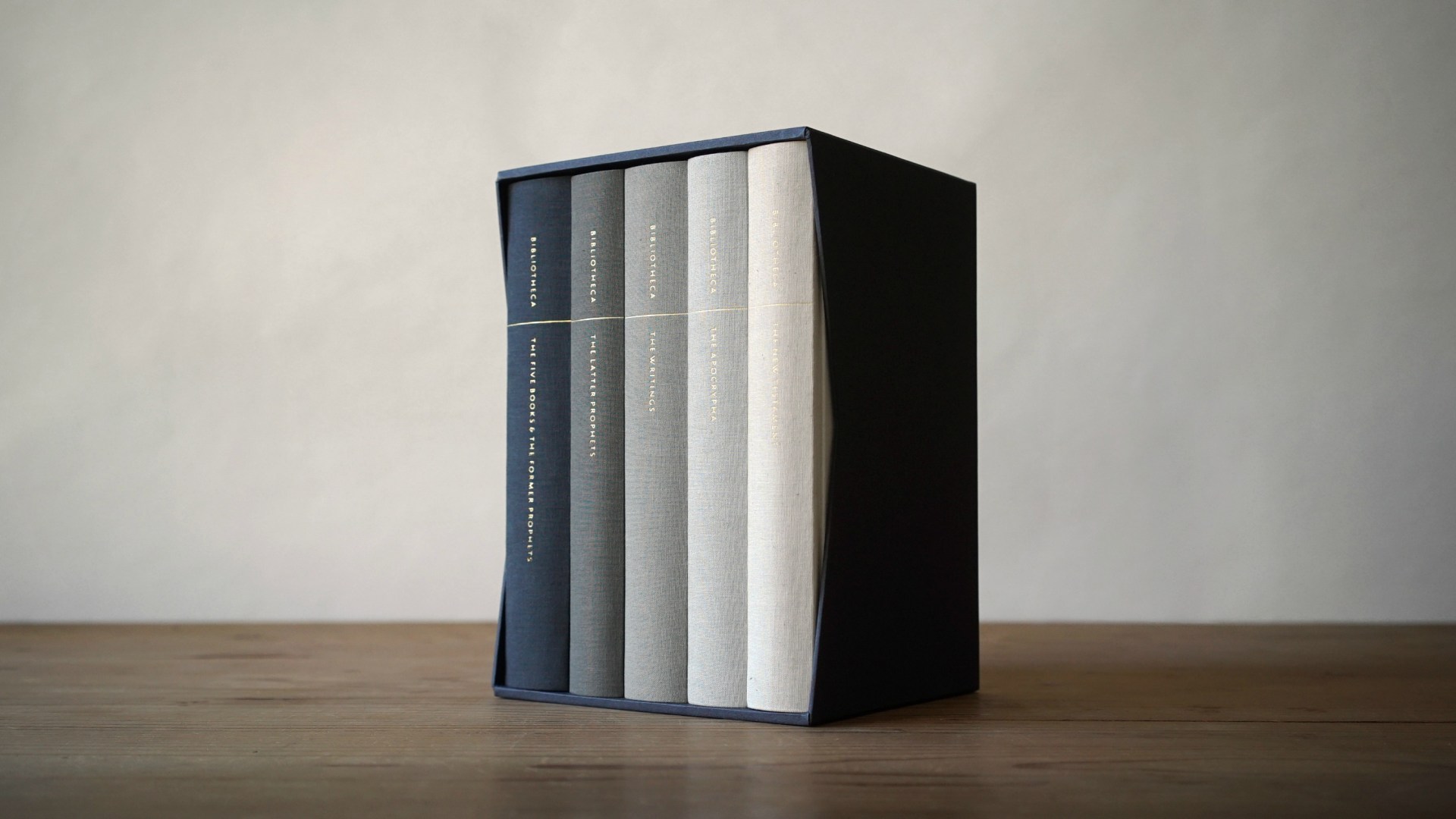

When his project to create a four-volume, single-column Bible raised $1.4 million—ranking among Kickstarter’s top 10 campaigns of 2014—the California-based book and type designer found himself overwhelmed at the scope.

Transforming the Bible from its familiar reference-packed pages to a format more like a novel proved to be far more complicated than removing chapter and verse numbers and footnotes. In addition to sorting out design elements and materials, producers had to choose how to present a text that readers have seen the same way for generations.

The timeline was pushed back as Greene used the additional funding for a professional revision of the American Standard Version (ASV), complete with copy editors, Bible scholars, and proofreaders to change archaic words like thee and thou and update verses whose translations have improved since the ASV’s original 1901 publication.

Then came the typesetting, as the team decided how to space each book of the Bible without the typical divides. For example, passages of Isaiah traditionally printed as prose got line breaks like poetry, a better reflection of their Hebrew format, said Greene.

“What I did not expect was that, through this process, my admiration and reverence for the text would deepen as it has—maybe tenfold,” he said. “This literature is so complex and interwoven. The deeper I dig, the more I discover.”

Finally, specialty materials caused delays at his German printer, which had to acquire new machinery and adhesive to bind the books. The 150,000 volumes shipped in 40-foot containers in October and are scheduled for delivery in December.

The completion of Bibliotheca coincides with a wave of multi-volume reader’s Bibles from major publishers. Enthusiasts for this format—which has come up as niche, alternative editions several times over the past century—believe it might finally take off among readers.

“It wasn’t purely aesthetics that drove people. It was the idea that text could be experienced in a less mediated way,” said J. Mark Bertrand, who runs the site Bible Design Blog. “I wouldn’t be surprised if after the success of Bibliotheca’s fundraising, a lot of people are seeing that as a template.”

Crossway, whose single-volume English Standard Version (ESV) Reader’s Bible released in 2014, debuted a new six-volume edition in October. The grey, cloth-bound books resemble Bibliotheca—as supporters on social media quickly noticed—but Crossway said its project had been in the works before the launch.

Holman Bible Publishers released the first versions of the King James Version (KJV) and New King James Version (NKJV) without chapter and verse numbers this fall, and a reader’s version of the new Christian Standard Bible (CSB) is due out in 2017, said Trevin Wax, Bible and reference publisher for LifeWay Christian Resources. Zondervan plans to release its New International Version (NIV) Reader’s Bible, in three different cover materials, next year.

The proliferation of Bible apps has not deterred reading the Bible in print, which remains the most popular method across age groups (according to American Bible Society research). Bertrand even believes this is somewhat causal: because today’s readers can instantly look up references on their phones, they’re free to read a Bible without them in the text.

The single column of text with generous margins and bigger type invites readers to stay longer, think deeper, and get “Scripture inside them, truly shaping the way they look at the world,” said Dane Ortlund, executive vice president of Bible publishing at Crossway. “In this age of constant distraction and multitasking, this edition encourages focused, immersive reading of the Bible.” [See a sample of the Reader’s Bible pages here.]

Because readers are so used to the tiny type and chapter organization of their Bibles, they rarely realize what the experience would be like to read without those elements.

“People say, ‘The form doesn’t really affect me. I just ignore it.’ Well, that’s not true because form and function do work together,” said Glenn Paauw, of the Institute for Bible Reading and author of Saving the Bible from Ourselves.

As a former vice president at Biblica (then the International Bible Society), Paauw oversaw The Books of the Bible, a reformatting of the NIV. His team focused on readability and reclaiming earlier literary forms; for example, the Gospel of Matthew was divided into five sections, according to repeating phrases in the text and thought to echo the five books of the Torah.

“When I see something that looks like a reference book, I tend to use it as a reference book—for looking something up rather than reading at length,” said Paauw. “[With reader’s Bibles], the chapters don’t function as stop signs anymore. You just keep reading because the story or that part of the letter goes on.”

Calvin College professor James K. A. Smith tweeted last month a picture of his multi-volume ESV Reader’s Bible, saying it “will change how I interact with Scripture.” The new editions released October 31.

The high-end leather-bound sets of the ESV Reader’s Bible run $499, the most expensive Bible Crossway makes. The clothbound versions are $199. Paauw speculates the price point may keep it as a niche product at first, but eventually readers will catch on.

“It’s exciting that 500 years after the Reformation—that’s a time that introduced us to reference Bibles—people might actually be getting back to a reader’s edition, which might finally reverse these horrible statistic about Bible reading and Bible literacy,” he said. According to the American Bible Society, about 60 percent of Americans wish they read the Bible more; most read it once a month or less.

Despite the benefits of the new, reader-friendly Bibles, it doesn’t take any particular format for biblical truth to be effective, cautions Wesley Hill, biblical studies professor at Trinity School for Ministry.

“Sticking with the standard one-codex version of the Bible can be a way of taking a stand with tradition—with the way the church has come to read Scripture,” Hill wrote for First Things in response to the Bibliotheca launch. “We don’t have to try to peel away centuries of encrustations to try to get back to some purer, less distorted version of the Bible.”

He’s still excited for his copy of Bibliotheca.