The arrival of millions of African Americans to the industrial North from the agrarian South over the course of the 20th century had more than just an economic and cultural effect. While many migrants joined churches in their new cities, helping to build key institutions that would ground their communities, others found the message of organized religion lacking.

Some left for Islam and off-shoots of Judaism and African spiritualism. Many found a home in urban folk religious movements. These sects often spoke directly to the plight of African American workers, most of whom had left Jim Crow only to find segregated Northern cities, racist labor unions, and race riots. These sects often preached that Christianity was the “white man’s religion” and offered a non-Christian and non-white centered paradigm for black people to liberate themselves from their oppression.

Today many Christians, especially those who live outside the city, may be unfamiliar with the history and context of those sects, which exist today predominantly in the inner city. Here’s three of the most common sects: the Moorish Science Temple of America (MSTA), Nation of Islam (NoI), and Black Hebrew Israelites (BHI).

Moorish Science Temple of America (MSTA)

The MSTA first began in the early 20th century under the guidance of Noble Drew Ali. Born in 1886, Ali was outraged by the treatment of black people during the Jim Crow era. He channeled this frustration into an attempt to provide a broader religious identity for black people.

Ali became obsessed with the idea that salvation for black people lay in their discovery of their true origin—descendants of the ancient Moabites. (In the Bible, Moabites are the descendants of an incestuous relationship between Lot and his daughter.) In today’s terms: Moors or, in this case, Moorish Americans. One actualized their Moorish identity by paying monthly organizational dues. Over the course of Ali’s lifetime, MSTA gained the most traction in the inner city, growing to nearly 30,000 followers.

Drew believed he was a prophet of Allah (other prophets included Jesus, Buddha, and Confucius), although the MSTA has no affiliation with orthodox Islam. Its teachings are found in the Holy Koran of the MSTA, a 60-page booklet with no resemblance to the Qur’an of Islam. The book contains “secret lessons” about the missing years of Jesus. Half of the book is plagiarized from The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus Christ, the second half from Unto Thee I Grant. Notably, both books are written by white people.

The Nation of Islam (NoI)

MSTA continued after Ali’s death in 1929, but it was soon overshadowed by another black religious group. In 1930, a clothing salesman named Wallace D. Fard appeared in the ghetto of Detroit with a message of liberation for black people marginalized by Northern whites.

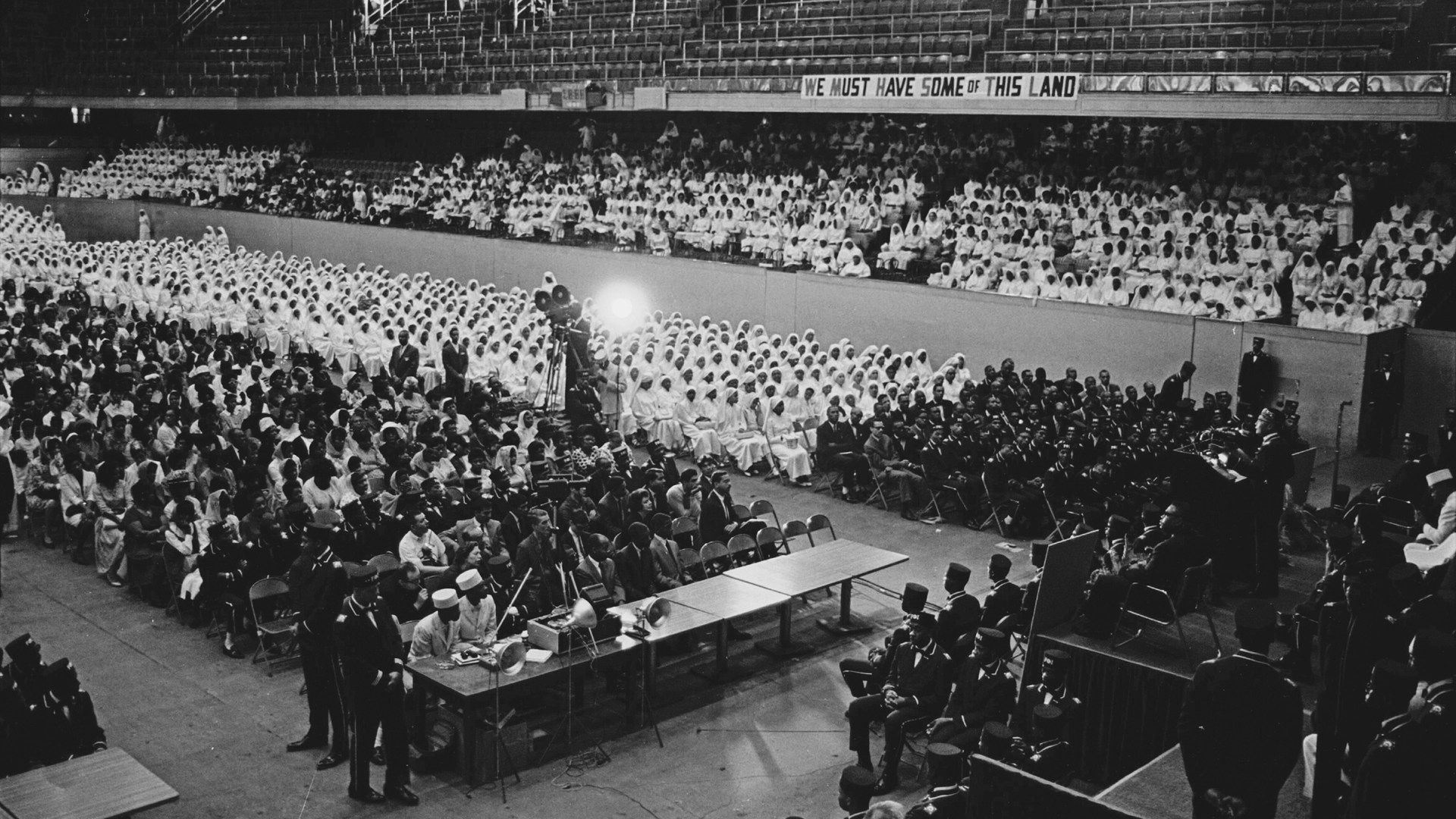

The early years of NOI appealed to the defiance of African Americans against white supremacy by identifying white America as a race of devils who could not be trusted. There was no salvation for the black man in a religion that historically had failed to provide justice for people of color in this country, early leaders taught. This wrong would be righted at Armageddon where the white man would be conquered by the black man.

Fard believed that by educating previously “downtrodden and defenseless” black people about God and themselves they would be able to experience “self-independence.” Part of knowing themselves was knowing their history: Blacks were descendants of the tribe of Shabazz, preached Fard, a lost people who were from the Lost Nation of Asia that had been slaves for over three centuries. Fard assumed the name Wallace F. Muhammad and claimed that he was divine and the long-awaited savior of the black man and woman.

In 1933, Fard’s chief assistant Elijah Poole assumed the leadership role of what soon became the NOI. According to Poole, Fard was a reincarnation of Allah and he was his messenger.

“We know we have a savior,” wrote Poole in his Message to the Blackman in America in 1965. “In 1877 a savior [Wallace Fard] was born. A savior is born, not to save the Jews but to save the poor negro. A savior has come to save you from sin, not because you are by nature a sinner but because you have followed a sinner.”

Black Hebrew Israelites (BHI)

The BHI is another group which gained a following in the inner cities. BHI claims Hebrew/Israelite ancestry, correlating the transatlantic slavery of Africans in America to Israelite slavery, per Deuteronomy 28. In the text, Moses warns the Israelites that future disobedience would result in God sending them “back in ships to Egypt on a journey” where they would consequently sell themselves as slaves to their enemies.

An incredibly decentralized religious movement, BHI have little convictional consensus. While some sects developed in the South before the Civil War, they took hold in inner-city mainstays in the 1980s when Yahweh Ben Yahweh and others began to broaden the BHI movement to incorporate sects such as House of Judah, the Lawkeeper, and the Commandment Keepers.

BHI does not have a universal authoritative text, though members will occasionally refer to the King James Version of the Bible and some pseudepigrapha. They generally maintain that the Trinity is a false teaching, salvation is only possible by calling on the true name of Jesus (Yahoshua), hell is a metaphor, and that many of the patriarchs of the Old Testament are black.