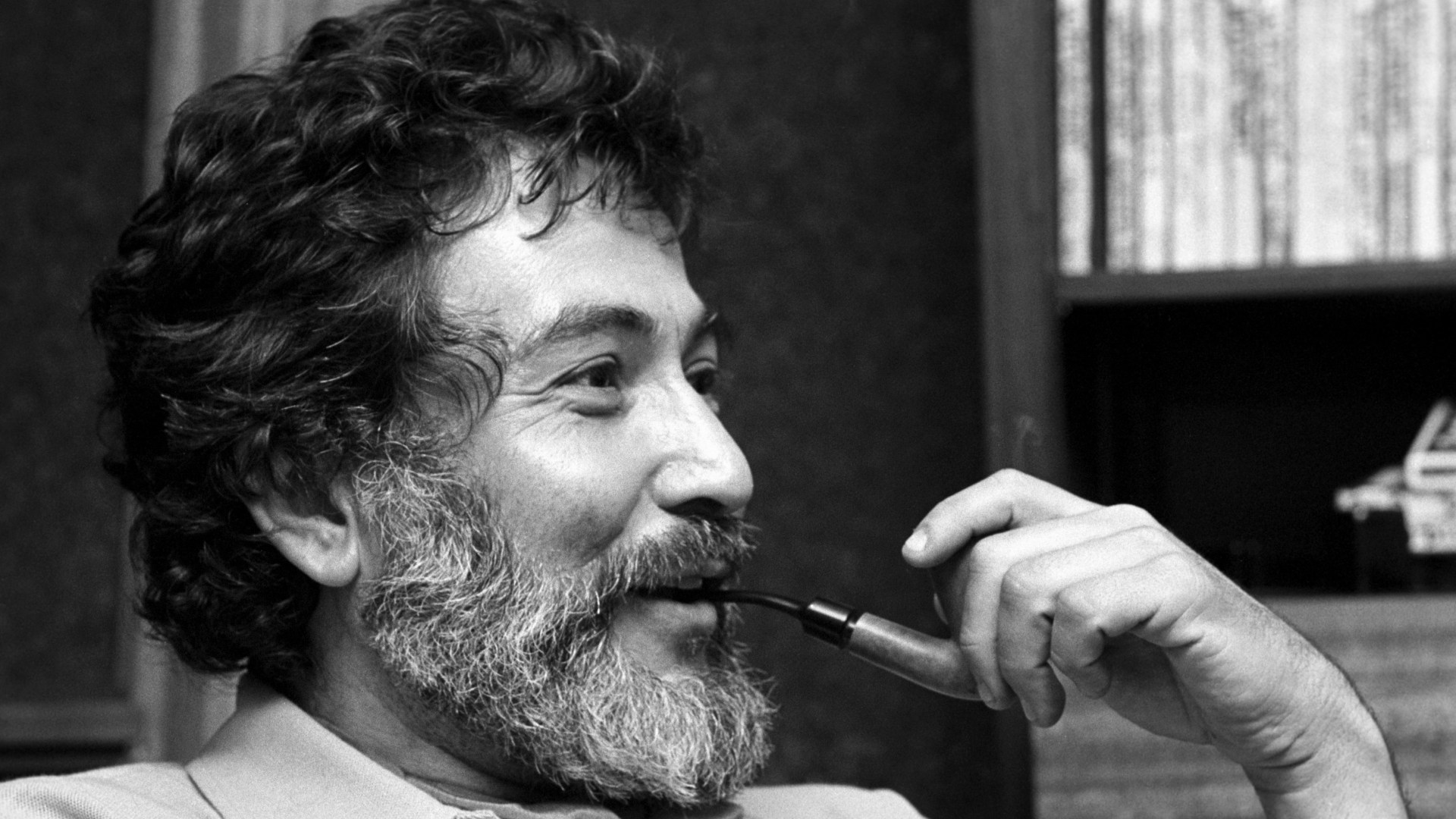

Nat Hentoff—author, jazz critic, and Village Voice columnist for 50 years—died this weekend at the age of 91. Hentoff was a liberal, progressive atheist—yet he profoundly shaped my Christian belief and practice.

In 1986, when he was already a wizened old civil libertarian and secularist pundit, Hentoff researched a number of high-profile cases of disabled infants who had been denied simple, life-saving procedures and instead allowed to die of starvation and dehydration. The resulting story, “The Awful Privacy of Baby Doe,” was published in The Atlantic and marked the awakening of Hentoff’s conscience on abortion.

He had to admit, he later explained in a lecture given to Americans United for Life, that the slope from abortion to infanticide to euthanasia is “not slippery at all, but rather a logical throughway once you got on to it”:

Now, I had not been thinking about abortion at all. I had not thought about it for years. I had what W. H. Auden called in another context a “rehearsed response.” You mentioned abortion and I would say, “Oh yeah, that’s a fundamental part of women’s liberation,” and that was the end of it.

But then I started hearing about “late abortion.” The simple “fact” that the infant had been born, proponents suggest, should not get in the way of mercifully saving him or her from a life hardly worth living. At the same time, the parents are saved from the financial and emotional burden of caring for an imperfect child.

And then I heard the head of the Reproductive Freedom Rights unit of the ACLU saying—this was at the same time as the Baby Jane Doe story was developing on Long Island—at a forum, “I don’t know what all this fuss is about. Dealing with these handicapped infants is really an extension of women’s reproductive freedom rights, women’s right to control their own bodies.”

That stopped me. It seemed to me we were not talking about Roe v. Wade. These infants were born. And having been born, as persons under the Constitution, they were entitled to at least the same rights as people on death row—due process, equal protection of the law. So for the first time, I began to pay attention to the “slippery slope” warnings of pro-lifers I read about or had seen on television. Because abortion had become legal and easily available, that argument ran—as you well know—Infanticide would eventually become openly permissible, to be followed by euthanasia for infirm, expensive senior citizens.

His words, although based in reason, not faith, demonstrate that all truth is God’s truth and that the truth of the Bible governs the nature of reality in ways that even the unbeliever can recognize.

Hentoff’s growing awareness of the nature of abortion-on-demand wasn’t an isolated incident; the 1980s raised consciousness for a lot of us on the issue of abortion. In 1987, a year following his Atlantic essay, I, too, became pro-life. For me it was the result of viewing The Silent Scream, a video showing via ultrasound a first-trimester abortion taking place.

As a cradle Christian who had never doubted Jesus or my saving faith in him, I, like Hentoff, had before my pro-life conversion relied on my own “rehearsed responses.” I had never needed to defend my faith (to others or, more importantly, myself) until I began to apply my Christian beliefs to the issue of abortion amid the culture wars.

But that was just the start. The abortion issue helped me to live out my Christian worldview more consistently and courageously. From the opposite end of the worldview spectrum, Hentoff’s example helped me to understand the holism of truth. The battle over abortion—or any “issue” at any time—must always be for the Christian a greater battle for truth, wherever, as Augustine said, it may be found.

Shortly after adopting my pro-life views, I began protesting at local clinics. Coincidentally (or, more likely, providentially), I had also just begun my PhD program. Imagine a pro-life Christian activist at the most liberal department in a liberal public university in one of the most liberal states in the country. As far as I know, I was the only Christian in my department. I was certainly the only one publicly opposing abortion. In such an environment, I knew I wouldn’t likely be popular—but I had no idea that I would be hated and silenced. I had thought we were all there to pursue truth in our learning, but it seems I was mistaken.

My officemate asked me to take my pro-life flyers down from our door (offering to take down her lesbian literature in return). A professor recorded a complaint about my protest activities in my grade report. Worst was how some professors and fellow students avoided eye contact with me in the halls. One student wrote a column in a student newspaper objecting to the pro-life week my club held on campus, exhorting students to spit on and kick the pro-lifers. The university ordered our club to cancel our display.

I was naïve enough to think that standing up for what I believed in would bring some respect even if others didn’t agree. Studying within the liberal arts, I thought truth might prevail. But I was mistaken. These liberals weren’t tolerant. They weren’t even truly liberal—not in the classical sense of freely pursuing knowledge.

I later came across Nat Hentoff’s 1992 book, Free Speech for Me—But Not for Thee: How the American Left and Right Relentlessly Censor Each Other. In the prologue, Hentoff explained that part of his inspiration was the oppression of pro-life activists and the failure of liberals to speak out against it—at last, a liberal thinker striving for consistency. His efforts helped me to see where Christians and conservatives must do the same.

Reading Hentoff’s work, I was awed at one for whom integrity meant more than merely marching in lockstep with his own kind. While Hentoff objected, rightly, in his book to the censoriousness of conservatives, he called out his fellow leftists for similar impulses, finding such behavior contradictory to liberal values.

As I began thinking through free speech issues, I realized that Christians, not liberal secularists, have more to lose from censorship. The legal cases piling up against my fellow pro-life activists and me attested to this. But even more important, I came to understand that not only do Christians have more to lose from restrictions on speech, but we have less reason to fear even wrong ideas.

The way to combat falsehood is not in suppressing it, but in countering it with truth. For just as light dispels darkness, so wisdom excels folly (Ecc. 2:13). The 17th century Puritan and poet John Milton was one of the first modern Christians to defend free speech. He did so by affirming truth’s undefeatable power:

For who knows not that Truth is strong, next to the Almighty? She needs no policies, nor stratagems, nor licensings to make her victorious; those are the shifts and the defences that error uses against her power. Give her but room, and do not bind her when she sleeps . . . And though all the winds of doctrine were let loose to play upon the earth, so Truth be in the field, we do injuriously, by licensing and prohibiting, to misdoubt her strength.

Let her and Falsehood grapple; who ever knew Truth put to the worse, in a free and open encounter? Her confuting is the best and surest suppressing.

In Milton’s day, suppression of truth was a matter of life and death. Nat Hentoff recognized that this is still true today. And when my university tried to prevent my pro-life student club from expressing our ideas about abortion in display of commemorative crosses, Hentoff was one of the first to call in support of our effort.

Despite my disagreements with Hentoff on other topics, to him I owe my understanding as a Christian that because we believe in and have access to the truth, we have the least to fear from the free and open exchange of ideas. When someone with such a dramatically different worldview recognized and upheld at great personal cost the belief that all lives are indeed created equal, I saw the power of truth at work.

Thank you, Nat. Your legacy of integrity and courage lives on.