His name may not be familiar to those outside Christian publishing, but few have impacted the church as much as Melvin E. Banks Sr., the founder and chairman of Urban Ministries Inc. (UMI). On May 2 in Colorado Springs at its annual Leadership Summit, the Evangelical Christian Publishers Association (ECPA) presented Banks with the Kenneth N. Taylor Lifetime Achievement Award for more than 50 years of excellence, innovation, integrity, and commitment to making the message of Christ more widely known.

Inspired by Hosea 4:6 where God says, “My people are destroyed from lack of knowledge,” he founded UMI in 1970 to create an African American Christian publishing house that would uniquely serve this audience. Today, UMI thrives as the largest African American Christian media and content provider, serving over 50,000 churches with curriculum, books, magazines, Bible studies, videos, teaching resources, and more.

Banks has been recognized with an honorary doctorate by his alma mater, Wheaton College, where he served as a trustee for many years. He has also been honored as a Moody Bible Institute Alumnus of the year and has been recognized for his achievements by many others, including the History Makers Foundation. His innovative use of video in Vacation Bible School has been widely duplicated, and his work has led to many companies becoming more ethnically and racially diverse in the reach and content of their publishing efforts.

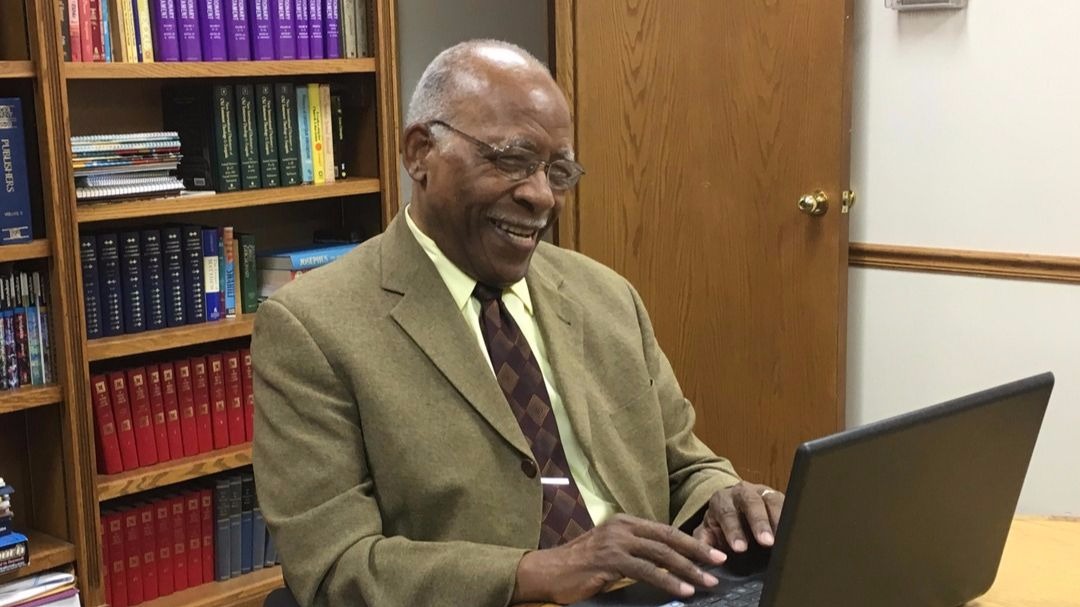

Theon Hill, assistant professor of communication at Wheaton College, sat down with Banks at UMI’s headquarters to learn more about his pioneering vision.

What was your background in publishing and media prior to UMI?

I had very little publishing experience prior to my work with UMI. In high school, I worked on the school newspaper. During my transition from Moody [Bible Institute] to Wheaton [College], I began to dream of a magazine that would be inclusive of people of color.

Around that time, I was invited to work at Scripture Press Publishers, one of the Christian publishers at that time. I initially resisted because I did not see any connection between what Scripture Press was, a white company located in what to me were the “boondocks” (white suburbia) and me, located in the city where all the black people were. Eventually, God laid it on my heart to accept the offer. This position became my introduction into the publishing industry. During my time there, I caught the vision that you could use ink on paper and duplicate it as a means of producing large quantities of content and that then could be distributed to the masses.

Why is it important for people of color to see people who look like them in biblical materials?

When I grew up, all the Sunday school literature was produced by white people and all the writing was done from a white perspective. All the biblical characters were portrayed as white people. It dawned on me that the material as published did not connect. It did not talk about the culture that African Americans lived and how they worshiped. This fueled my desire to produce material that was more relevant to the African American context.

The geographical center of the Scripture spanned from North Africa to the southern tip of Europe; yet, biblical literature at the time featured characters with northern European features, so we sought to provide more accurate biblical representations.

What challenges did you face when you started UMI?

At that time, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was working to gain civil rights for African Americans. There was this attitude that we in the black community needed to do something to advance this agenda.

At the same time, there was this notion being perpetrated that African Americans needed to take initiative, to take power. These perspectives dominated black America during the 1960s. The need for equality and social justice on one hand and the need for Afrocentric control and power on the other. As UMI began, we faced the difficulty of balancing these perspectives in the materials that we produced.

What support did you receive from other Christian publishers?

Interestingly, one of my first contacts did not see a need for producing material that was contextualized. In pursuing financial support, one colleague told me, “Well we’re already trying to integrate our materials and that’s all you really need. Put some black people in our materials and that will be satisfactory.”

Fortunately, I was working for Scripture Press and they eventually hired Jim Lemon, who understood niche marketing, so he helped me communicate the merit of my vision to leadership, so Scripture Press assisted me in the early days. In addition, other organizations like Zondervan and Tyndale House offered support for the vision.

Yet, despite this support, we still did not have adequate funds. When we started publishing, we only had about 30 percent of what we needed financially. We began with faith in the response of the people we were serving and with confidence that if God was in it, he was going to make it happen one way or another. Because of our financial position, we had many difficult experiences to learn from before we began to break even.

What distinguished the materials produced by UMI?

One of the great deficits that I discerned among African American youth was a lack of self-esteem, a lack of appreciation for who they are. They appreciated opening a book and seeing people looking like them. While we were teaching the Bible, we were also affirming them as human beings and affirming them in accepting themselves as they were. This proved effective in helping a whole generation of young people learn who they were in Christ and accept Jesus Christ as their Savior.

We also recognized that many of our young people lacked knowledge and an appreciation of our history. So, we prioritized profiles of inventors, doctors, and lawyers in our materials. We lifted the horizons of many of our young people, so that they can realize that they can achieve just as much as other people.

How did the black community receive UMI?

People were very appreciative that somebody was finally doing something about the great need. However, we discovered pockets of resistance to our practice of not portraying Jesus as white. Eventually, of course, we won them over and today there is very little question about doing this sort of thing.

Apart from that, we faced battles when we challenged traditional approaches to teaching biblical content. People had developed habits they were not quick to relinquish. For example, our inclusion of film into Vacation Bible School curriculum required us to convince churches of the educational potential of film within this context and then provide training on successfully incorporating it. Innovative approaches to theological education became a defining trait of UMI’s engagement with the black community. From contextualized resources to digital media, these efforts have strengthened the pedagogy that churches rely in on in sharing the gospel of Jesus Christ.

How has the black church changed since UMI started?

That’s a good question. Two primary developments come to mind: the evolution of the pastor’s role and the nature of the church’s engagement with issues of race. Historically, the pastor served as the final authority on every decision. Yet, increasingly, people have become more educated and begun to question the absolute role of the pastor. They have started to look for leadership that is more responsive to the people in the pew.

Second, black and white congregations have experienced a growing willingness to dialogue on the causes of stubborn racial barriers. Even though we’ve occupied the same geography for hundreds of years, social distance persists between blacks and whites, especially in the church.

What are some of your more recent initiatives?

We seek to encourage people to use their God-given abilities to impact everyday life. One of the initiatives that we have taken on in recent years involves helping people understand the relationship between faith and vocation in order that they might use their abilities in the workplace. That, of course, will produce greater economic advances. As everybody knows, the need in our day is economic development to enable people to support themselves and their community.

How do you understand the resurgence in racial tensions?

If we had a good answer, it probably wouldn’t be asked. The reality is that there is an issue of what causes the problems that exist today. When I listen to the dialogue that takes place today, it seems as if people take the position that all the violence suddenly came upon the African American community and all we need to do is find what triggered it and send in enough people to stop it. This seems to be the attitude of many of the politicians. But I’m among those who don’t think it’s quite that simple, and UMI can help teach about the complexity of the issues.

The violence in places like Chicago stems from a long process of deprivation that needs to be addressed. It includes, of course, having a family structure that would help to convey values. It includes dealing with the inequities in housing, education, job discrimination, and a host of other issues. The absence of equality in those areas has brought about a great amount of frustration.

I should include the unjust incarceration of many of our young men. They go into prisons, come out without any resources, nowhere to go, no food, and some resort to violence as a way of survival. If we were to grapple with these issues that have historic standing, then we would begin with the causes of the violence that takes place. Unless we are willing to deal with these underlying causes, then all the troops in the world will not fix the problem.

What gives you hope for racial progress in the coming decades?

UMI began during a period of heightened racial tensions in our nation. Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Medgar Evers had all been assassinated. While we continue to deal with some of the same issues now, I draw hope from the fact that people are engaged with issues of race today who previously viewed the topic as irrelevant. God has awakened his people to the centrality of equality, justice, and love to the gospel message. When I see churches [that were] previously at odds come together to address contemporary inequalities in local communities and witness preachers advancing biblical perspectives on racial justice to their congregations, I find hope for the future.