The tragic events in Charlottesville have captivated the attention of the nation, plunging us, yet again, into another period of deep soul-searching over our anguished racial history. President Donald Trump drew criticism from both sides of the aisle for his reluctance to condemn white nationalism specifically in his initial remarks.

As a scholar of political rhetoric, I understand, yet strongly disagree with Trump’s strategy in refusing to condemn white nationalism specifically. A vocal part of his base aligns with this philosophy, leaving him little incentive to risk alienating them. When former Klansman David Duke endorsed Trump during the campaign, the candidate expressed similar hesitancy in distancing himself from white nationalism.

Trump deserves strong criticism for his failure to specifically and clearly condemn white nationalism. The lure of power and votes do not justify his silence. Yet, to criticize an unpopular president is easy. Perhaps the harder, more difficult task we face in the wake of Charlottesville is to consider how we as citizens and Christians engage in a similar type of silence on a regular basis. Many of us mobilize in defense of ideals of equality every time an incident like Charlottesville occurs but quickly retreat to our comfort zones when public attention dies down. Daily battles for equality in church, education, employment, and the criminal justice system are much harder to maintain.

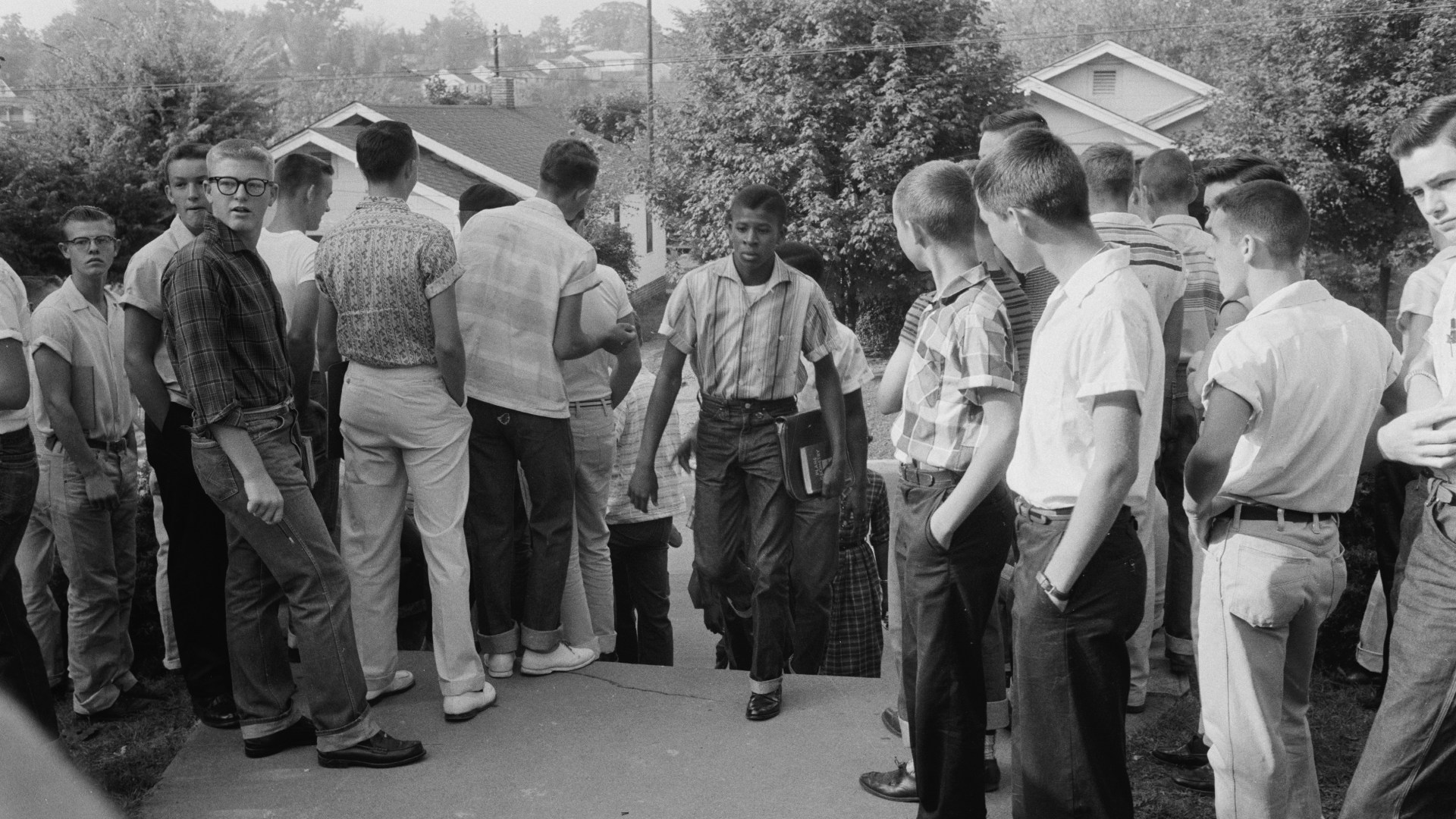

Trump’s silence on white supremacy was not an aberration but a cultural norm. Our disgust with his statement threatens to blind us to the ways in which the American imagination has consistently made room for the ideas of white supremacy to exist alongside core values like freedom, justice, and equality. Accommodating racism is as American as apple pie.

This Is Who We Are

Racial tensions have skyrocketed to their highest levels in 25 years. The common narrative traces this recent period of unrest back to the murder of Trayvon Martin. But our attempts to grapple with events in Charlottesville and Charleston fail to identify the link between our communal history of accommodating racism and contemporary tensions. Neither the nation nor the church has demonstrated a sustained commitment to confronting white supremacy. At key moments, Christians have advocated for the abolition of slavery, death of Jim Crow, and the end of mass incarceration, but the commitment to equality has consistently languished over time. Our lack of sustained commitment to biblical justice keeps the soil of racism and white supremacy fertile for the James Fields Jr.s and Dylann Roofs of American culture to grow into domestic terrorists.

Deep down, I suspect many of us recognize the inadequacy of our past and present efforts to combat racism. Yet, as James Baldwin observed, “people find it very difficult to act on what they know.” We content ourselves with annual celebrations of our national independence without wrestling with the hypocrisy of a freedom declaration against the backdrop of slavery. We paint a picture of gradual progress on racial fronts since the Emancipation Proclamation but fail to acknowledge that the Compromise of 1877 injected new life in white supremacy, giving racists an unparalleled opportunity to execute violence against people of color for decades.

Events along these lines are not inconsistent with our national identity. In fact, they are a part of our DNA. They illustrate how our country has tolerated pervasive forms of racism—and even genocide—to gain power, wealth, and influence. The current fight to preserve positions of honor for Confederate monuments reflects an unwillingness to confront the vicious legacy of white supremacy. The goal of these removal efforts is not, as some argue, to whitewash the past, but to recontextualize it. Defense of an institution that legitimated forms of physical, psychological, and sexual trauma is not a cause to honor but lament.

A History of Habits

Sadly, the church frequently surfaces as a guilty culprit in the story of America’s embrace of white supremacy. Not only did the church fail to provide a consistent counterpoint to white supremacy in the broader culture, but it also harbored it within the walls of congregations around the nation. When slave masters refused to evangelize their slaves during the early part of the 18th century, the church, rather than condemning slavery, went to great lengths to assuage the masters’ concerns. Faith leaders like Thomas Secker, Archbishop of Canterbury, reconciled the tension between slavery and Christianity with a perversion of Paul’s letters:

As human authority hath granted them none, of the Scripture, far from making any alteration in civil rights, expressly directs, that every man abide in the condition wherein he is called, with great indifference of mind concerning outward circumstances: and the only rule it prescribes for servants of the same religion with their masters, is not to despise them because they are brethren, but to do them service.

Subsequently, leaders in the Southern Baptist Convention, American fundamentalism, and other segments of Christianity made similar efforts to employ theology in the service of white supremacy. These compromises, as Martin Luther King Jr. noted, effectively “segregated…churches from Christianity.”

The practice of accommodating white supremacy is not unique to white America. People of color have often deployed accommodation strategically, hoping that it will lead to greater acceptance by whites. Booker T. Washington, in his famous Atlanta Exposition Address, embraced the logics of “separate but equal,” expecting blacks to experience upward mobility as they demonstrated their worth to white America. W. E. B. DuBois called on blacks to avoid racial activism during the First World War, believing that loyalty to the nation during this difficult moment would produce greater acceptance during the post-war period. Even my personal hero Dr. King hesitated to oppose racists in the Democratic Party in 1964, believing that accommodation would produce greater gains for blacks in the long term.

Scripture and history repeatedly warn that accommodating sin never produces greater holiness. Washington’s bargain failed spectacularly during one of the most intense periods of racial violence our nation has ever seen, black soldiers returning from the First World War were lynched in the streets while still in uniform, and the nation grew weary of racial advocacy following the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Our history of accommodation has instilled in us what Princeton professor of religion Eddie Glaude labels “racial habits” in his recent book Democracy in Black: How Race Still Enslaves the American Soul. Racial habits surface in “the ways we [often unconsciously] live the belief that white people are valued more than others.” Our responses to current events often reveal these racial habits. We devote time, resources, and social media platforms to the precious life of Charlie Gard, but we fail to give the same sort of attention to the hundreds of precious people who perished during the same time period in Venezuela due to political unrest. The disparities in our engagement reveal a fundamental gap in how we value different lives.

‘You Have Not Yet Resisted’

People often ask me how the church should respond to this legacy of accommodation. Recently, I sat down with my Bible to spend some time in God’s Word. When I read the Scripture, I study Scripture inductively, seeking to apply it to my personal, family, and communal life. When I read Hebrews, the words practically leapt off the page at me: “In your struggle against sin you have not yet resisted to the point of shedding your blood.” Of course, I’m not suggesting a violent insurrection in response to the problem of racism, but if the church displayed the kind of radical resolve this passage speaks to, our society would be unrecognizable. As far back as the 19th century, theologians recognized the church’s untapped potential to positively impact race relations. Albert Barnes argued, “There is no power out of the church that could sustain slavery an hour, if it were not sustained in it.”

Our current racial situation is bleak. With every new incident, my ability to remain hopeful is tested. At age 31, I’m sick and tired of seeing unarmed black men killed at the hands of law enforcement. My heart breaks for the black and brown children trapped in underfunded, understaffed schools that prioritize testing over education. I weep for incarcerated individuals whom we isolate from society instead of rehabilitating for reentry.

Yet, in the midst of these painful realities, the church is called to speak boldly to the power of the gospel. This task requires pastors who faithfully preach against the sin of racism in its structural and individual forms. It demands congregations who refuse to sit on the sidelines as long as injustice is a norm in their community, becoming advocates for racial justice through advocacy, protest, and partnerships.

My prayer is that God will raise up a generation of his people who reject accommodation and embrace the struggle for racial justice as an outgrowth of the gospel. As Frederick Douglass observed, “If there is no struggle there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom and yet deprecate agitation are men who want crops without plowing up the ground; they want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters. … Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.”