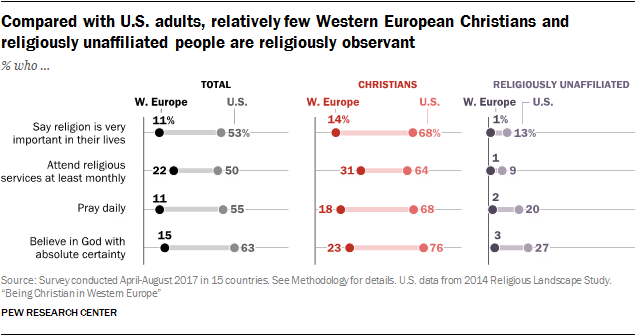

Religiously unaffiliated Americans are, unsurprisingly, less likely than their Christian countrymen to attend church regularly or say religion is important in their lives. However, on several common measures, “nones” in the United States exhibit nearly equal levels of spirituality as self-identifying Christians in Western Europe.

A new study by the Pew Research Center, surveying more than 24,000 individuals across 15 countries in Western Europe on their religious beliefs and practices, reveal striking disconnects between Western Christians across the Atlantic.

Equally striking is how similarly religious nones in the United States and Christians in Western Europe match up:

- Only 27 percent of American nones say they believe in God with absolute certainty; only 23 percent of Western European Christians say the same.

- Only 13 percent of American nones say religion is “very important” in their lives; only 14 percent of Western European Christians say the same.

- Only 20 percent of American nones say they pray daily; only 18 percent of Western European Christians say the same.

“By some of these standard measures of religious commitment,” stated Pew researchers, “American ‘nones’ are as religious as—or even more religious than—Christians in several European countries, including France, Germany and the UK.”

How can it be that self-identifying Christians in Europe describe less religious behavior than Americans who don’t claim any religious affiliation at all?

Part of the key to understanding this riddle may lie in semantics: What do people mean when they identify as Christian?

About 7 out of 10 Western Europeans call themselves Christians (according to the median percentage across the 15 nations surveyed). However, the majority are non-practicing, which is defined by Pew as attending religious services less than once a month. Only 2 out of 10 attend church monthly or more.

Across the 15 countries studied, a median of 79 percent of self-identifying Christians say they believe in God, ranging from 93 percent of believers in Portugal to 59 percent of believers in Sweden.

No national Christian population in Western Europe puts a high premium on evangelism, with a median of only 8 percent of believers saying they try to persuade others to adopt their religious views.

Fasting during holy times and wearing religious symbols are also uncommon practices in Western Europe. About 24 percent of those surveyed say they tithe, though this ranged from 43 percent in Portugal to 18 percent in the United Kingdom.

Among the largest segment of the Western European population—non-practicing Christians—less than half believe God is all-knowing (34%), all-powerful (26%), or all-loving (47%). Most practicing Christians assert God’s omniscience and his all-loving nature, but barely half agree that God is all-powerful.

A separate Pew study found that American Christians are far more likely to agree on each of these three characteristics of God than their European counterparts.

The belief that God will judge all and that he communicates with them regularly are also relatively rare among Christians in Western Europe, though more common among regular church attenders.

“Religion” and “spirituality” also manifest in somewhat different ways in Western Europe than Americans are accustomed to in their own country.

In the US, “spiritual but not religious” is a popular creed, claimed by 27 percent of the population. Not so in Western Europe, where a median of 11 percent across the 15 nations identify as such. In contrast, 15 percent say they are “religious but not spiritual.”

Meanwhile, 24 percent of Western Europeans say they are “both religious and spiritual,” compared to 48 percent of Americans. Among the Europeans, the largest group belongs to the “neither religious nor spiritual,” claimed by 53 percent.

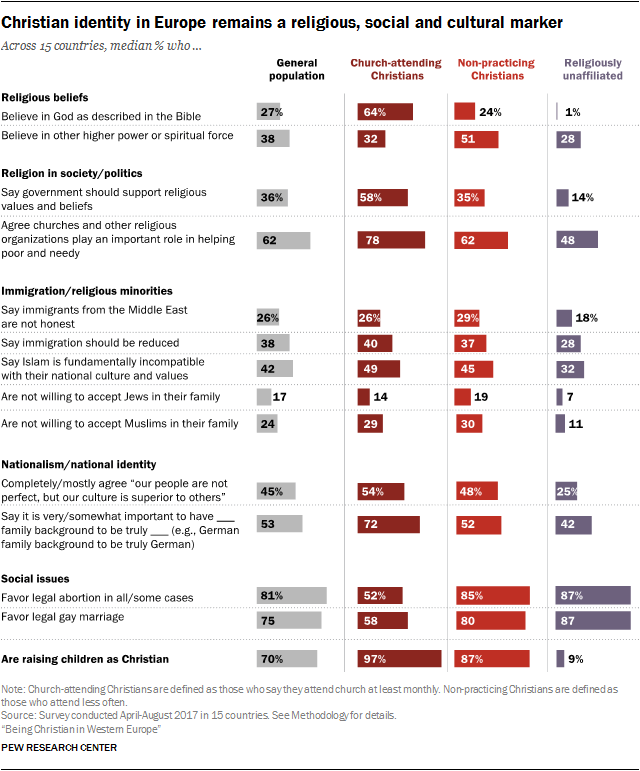

Still, if it sounds like Christian is a term with loose daily-life significance in Europe, that’s not the case. The Pew study included nearly 12,000 non-practicing Christians and found that self-identifying as a Christian—even among those who rarely participate in religious services—was still a “meaningful marker” in Western Europe.

“It is not just a ‘nominal’ identity devoid of practical importance,” stated Pew researchers. “On the contrary, the religious, political and cultural views of non-practicing Christians often differ from those of church-attending Christians and religiously unaffiliated adults.”

Non-practicing Christians generally do not believe in God as described in the Bible, but do generally hold positive views of church institutions. They also express nationalist sentiments, though Western European churchgoers have stronger views on both counts. Among Christians in every country analyzed, more said they are very proud to be a citizen of their nation (50% median) than said they were very proud to be a Christian (33% median).