Throughout my teenage years, a photograph of a young Honduran boy was as much a fixture of my family’s stuccoed Southern California home as the old refrigerator on which it hung. I had never met this child, whose smiling face greeted me any time I wanted a glass of milk, but we weren’t entirely strangers either, having exchanged letters on occasion. Truth be told, there was little chance I could have located Honduras on a map. All I knew was that my pen pal was struggling to make it and that supporting him was one small way that my family lived out its faith.

Looking back now, it seems remarkable to say, but during all the years that photo hung in the sun-soaked kitchen of our Orange County abode, it never once struck me as out of place. We were just one of many families I knew that had chosen to sponsor a child through World Vision International. Since its 1950 founding, the organization has evolved into nothing short of a philanthropic juggernaut, touching the lives of some 120 million young people in 95 countries last year alone.

But how did such photographs—not to mention the acts of transnational giving that they are intended to motivate—become so ubiquitous in American evangelical households? And how did evangelical institutions become such important players in international relief and development work in the first place? Tufts University historian Heather D. Curtis answers these questions and more in her brilliant new book, Holy Humanitarians: American Evangelicals and Global Aid, which shows that evangelical leadership in these realms significantly predated the tidal wave of postwar generosity that gave rise to organizations such as World Vision. Even as Curtis unearths this longer history, she underscores the urgency of ongoing moral reflection: After all, as her story makes clear, love of one’s global neighbor has sometimes come with dubious strings attached.

Mix of Motives

Holy Humanitarians transports readers back to the turn of the 20th century, when famed preacher Thomas De Witt Talmage and savvy entrepreneur Louis Klopsch partnered to turn a weekly newspaper, the Christian Herald, into a “medium of American bounty to the needy” around the world. Their mission had magnetic appeal: The paper soon attracted some quarter million readers, becoming by far the most widely read religious periodical in the country. The vast size of the readership boded well for the editors’ hopes that the Christian Herald could do good on the home front too. They viewed international benevolence work as a means of unifying America’s Protestant majority, which was increasingly divided along theological lines and fearful about the nation’s rapidly changing demographics. Perhaps the paper could provide just the boost that “Christian America” needed.

Thus a complicated mix of motives gave shape to the humanitarian work that Talmage and Klopsch undertook. When a severe famine broke out in Russia in 1892, they seized the moment, calling for donations to support that country’s starving people. An enthusiastic response could hardly be taken for granted. At the peak of the Gilded Age and with so much want on display in their own neighborhoods, would American Christians prioritize the needs of those an ocean away? As Curtis skillfully documents, Talmage and Klopsch did not leave the matter up to chance. Striving to generate a powerful emotional response in their readers, they published stories and images that graphically depicted the extent of human deprivation. Meanwhile, they set about “framing famine relief as a spiritual discipline,” one which also would redound to the benefit of American diplomatic relations with Russia.

This innovative set of rhetorical and visual strategies could be used to recast enemies as neighbors, as became clear in the immediate wake of the Constantinople earthquake of 1894. Talmage and Klopsch argued that, by extending aid to the afflicted, American evangelicals could contribute to “further breaking down the old barrier of antagonism that has existed for generations between Moslem and Christian.” But their empathy-inducing tactics could just as easily be weaponized. As word of Turkish atrocities against the Armenians spread, the Christian Herald’s editorial position rapidly shifted. Before long, Talmage and Klopsch were lionizing Armenian Christians at the expense of “barbarous” and “fanatical Muslims.”

It would not be the last time the Christian Herald indulged in what Curtis aptly calls “tribal charity.” When the United States declared war on Spain in the spring of 1898, Talmage and Klopsch abruptly stopped advocating for peace. Taking up arms was the most benevolent way forward, they argued. “By interpreting the nation’s military campaign against Spain as a divinely inspired ‘crusade of mercy,’” Curtis writes, “Klopsch and Talmage insisted that Christian charity remained the driving force of American foreign policy.” Cuban and Filipino independence fighters saw things differently, as did a diverse, homegrown coalition of American anti-imperialists.

As criticisms of US military aggression mounted, Talmage and Klopsch—eager to salvage the nation’s image as “the Almoner [or almsgiver] of the World”—put out a call for donations to help the people of India, who were themselves beset by famine. Here, again, there was no guarantee that readers would be moved to act. After all, virulent strains of scientific racism ran rampant in many white Christian circles during these decades. The Christian Herald never succumbed to theories about the biological inferiority of people of color; Talmage even went so far as to declare that “our Christ was an Asiatic.” But the editors nevertheless made clear distinctions between the “civilized” and the “heathen.” Little wonder that their humanitarian campaigns on behalf of Indian and Chinese peoples cut at least two ways.

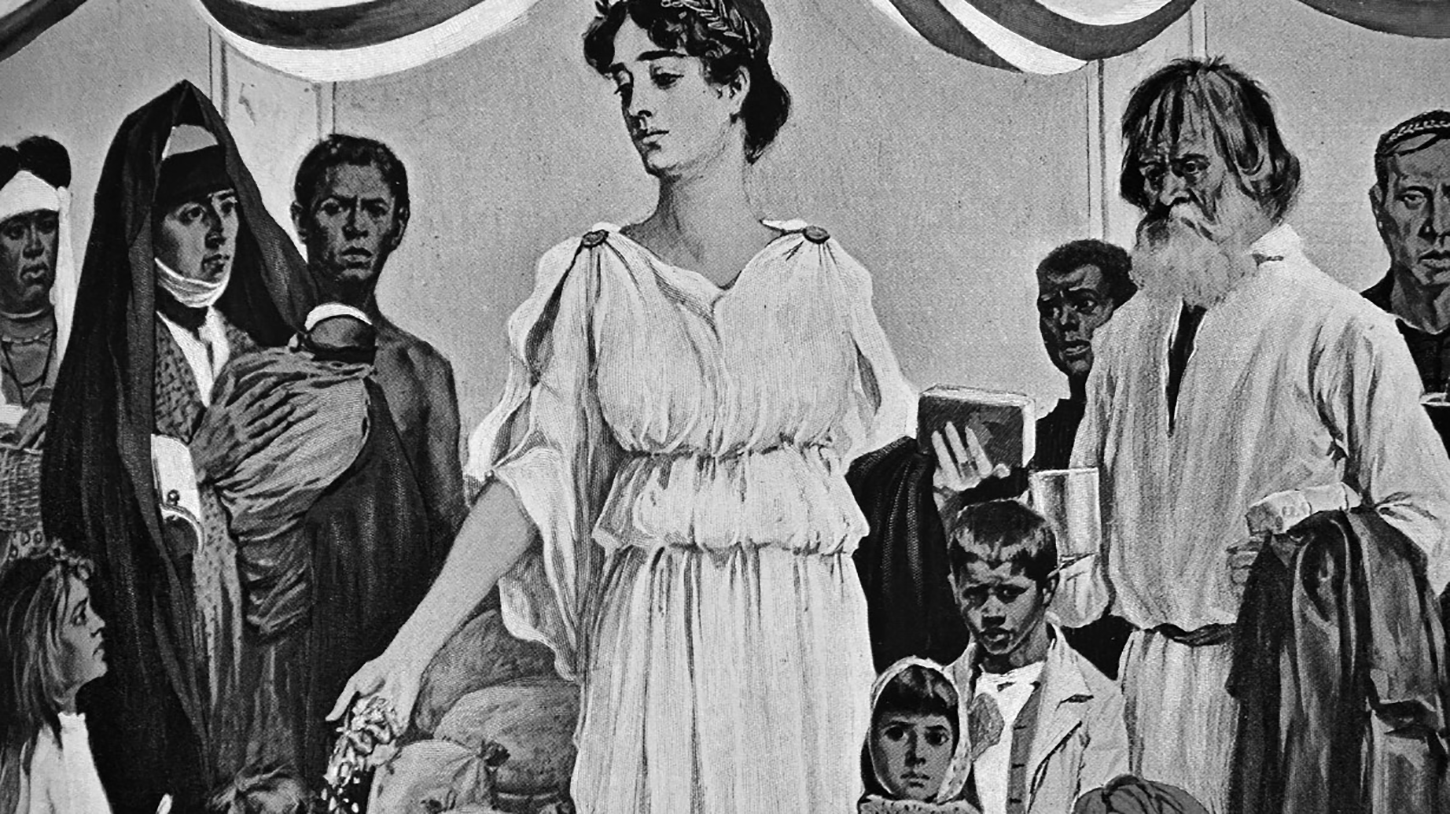

As Curtis perceptively argues, their “heartrending depictions [of suffering] worked to broaden American almsgivers’ vision of humanity and enlarge evangelicals’ sense of responsibility toward racial and religious ‘others.’” But there were serious drawbacks too. As she goes on to point out, these “harrowing accounts and photographs … reinforced the social, spiritual, and civilizational hierarchies that helped fuel the global expansion of imperialism while undermining efforts to promote Christian communities of equality.”

An Encouragement and a Warning

Amid all of their international activism, Talmage and Klopsch did not neglect the stark inequalities pressing down on those much closer to home. They published Christian socialists like Charles Sheldon—best known for the social-gospel novel In His Steps, which first popularized the question “What would Jesus do?”—and pushed back hard against the proponents of scientific charity, who insisted upon a distinction between the “worthy” and “unworthy” poor. New York City’s Bowery Mission, which Talmage and Klopsch helped to sustain, still serves all comers to this day.

During a period marked by rising nativism, the Christian Herald opposed closing the nation’s doors, championing instead an assimilationist vision that offered new immigrants a place in American society, albeit one with some serious constraints. Given how extraordinarily attuned they were to suffering and distress, it is all the more striking that Talmage and Klopsch never once commented on the gruesome lynchings of black Americans and the growing entrenchment of a staggeringly oppressive Jim Crow regime. Their silence seems especially deafening, Curtis rightly emphasizes, when compared with the death-defying activism of black Christians such as Ida B. Wells. As hard as Talmage and Klopsch worked to expand the category of “neighbor,” there remained sharp—even lethal—limits to their efforts.

Readers will find Curtis to be a trustworthy guide through the maze of thorny questions raised by her story. There can be no doubt that Talmage and Klopsch truly relieved much suffering. The capacity of secular agencies would eventually surpass that of religious ones, but for a long season the Christian Herald ran neck-and-neck with the likes of the American Red Cross (the rivalry between the paper’s editors and Clara Barton is one of the many enjoyable subplots in Curtis’s book). But the Christian Herald’s practice of benevolence was laced with a variety of problematic ideas, assumptions, and motivations, and so in the process Talmage and Klopsch also, often unwittingly, inflicted real harm. The holy humanitarians of today—including everyone from the heads of major philanthropic organizations to low-level sponsors of faraway children—would do well to ponder this book’s insights. Both the encouragement and the warning it offers are gifts in their own right.

Heath W. Carter teaches history at Valparaiso University. He is the author of Union Made: Working People and the Rise of Social Christianity in Chicago (Oxford University Press) and a co-editor of Turning Points in the History of American Evangelicalism (Eerdmans).