Unlike writers of passing fame, a classic author speaks a new word in every generation. Who could predict that our distracted texting and twittering could reveal more insights from Pride and Prejudice? But last spring I saw them pointed out in an excellent student paper on “Listening in Austen’s Novels.” And if you’re looking for someone beyond Jordan Peterson for insight on today’s crisis of masculinity, try Homer to learn how the son of Odysseus becomes a man.

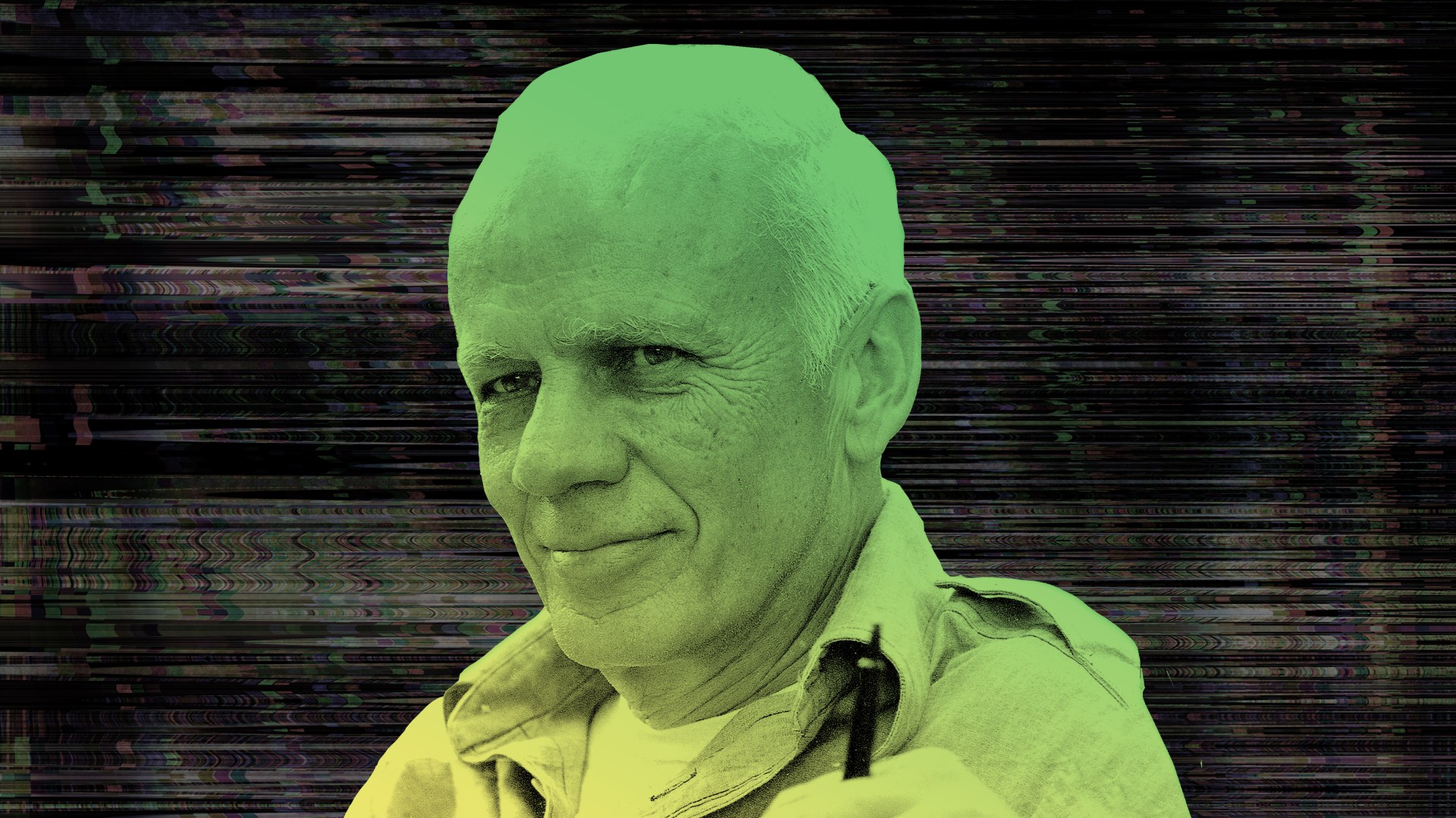

Walker Percy and the Politics of the Wayfarer (Politics, Literature, & Film)

Lexington Books

230 pages

$102.13

Walker Percy (1916–1990) wrote before the current “golden age for dystopian fiction,” as The New Yorker termed it last year—without apparent irony. But in the dystopian settings of many of this Catholic writer’s novels, from The Moviegoer (1961) through The Thanatos Syndrome (1987), you’ll find a persistent relevance. Their hyperbolic depictions of cultural polarization, racial tension, and medicalized evil could be satires on today’s news.

In Love in the Ruins (1971), for instance, future civil strife is simmering among the African American “Bantus,” the far-right Knotheads, and their opposite number, the “Leftpapas.” The main character, Tom More—a psychiatrist, alcoholic, and self-described “bad Catholic”—is hunkered down in an interstate cloverleaf, cradling his carbine and scanning the landscape for a sniper.

To test whether you’ll like Percy’s satire, consider More’s description of a far-off, rectangular patch of green: “It is the football field of the Valley Forge Academy, our private school, which was founded on religious and patriotic principles and to keep Negroes out.” Percy is employing a favorite satirical tool here that requires you to do several things at once: to recognize immediately its outrageously racist and hypocritical backstory and to distance yourself from anyone who isn’t capable of such recognition. Beyond this, if the sentence doesn’t make you smile—or at least grimace—Percy probably isn’t for you.

Beyond Cause and Effect

I’ve chosen this example because the strongest chapter in Brian Smith’s Walker Percy and the Politics of the Wayfarer deals with race. Although Percy didn’t like being limited by the “Southern writer” label, Southern he was and Southern he remained. Percy was raised in the Deep South, and he returned to live near New Orleans after earning a medical degree from Columbia and battling tuberculosis in upstate New York. In the few novels that end with the promise of restored relationships, such as The Second Coming (1980), Percy’s characters also settle in the South. Because the South has a “greater sense of place,” Smith explains, it has more potential for resisting the phony cures for alienation that American culture promises: psychotropic drugs, esoteric religious fads, expert advice on sex, and above all, the autonomous self.

And yet, because traditional Southern culture has owed more to stoicism than to anything else, even the most honorable white characters in Percy’s novels and essays rarely advance beyond paternalism. Percy’s model for this type was his older cousin, “Uncle” Will, who raised him and his brothers after the suicide of their father and the death of their mother. Uncle Will stood up to the newly resurgent Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, but as Percy writes, the “very man who will … even risk his life to protect Ol’ Jim from the lynch mob, is also outraged when Jim’s sons demand better schools and better police.” True enough. But Smith admits that even Percy, himself a devoted Christian, often provides “little more than a starting point and a clue to how racial reconciliation might proceed.”

That admission suggests a limit to Smith’s approach as well. As far back as 1961, Percy used “wayfarer and pilgrim” as terms for “the Judeo-Christian notion that man is more than an organism in an environment.” But wayfarers are not noted for building political communities. And as other Percy scholars have acknowledged, writing about Percy and community in any large, political sense is fraught with difficulty. Smith’s book has excellent insights on Percy’s relevance to race, social science, and philosophy. But he admits that Percy’s “wayfarer” is primarily searching for “places of rest and support,” which is hardly as robust a political vision as one finds, for instance, in a Southern contemporary like Wendell Berry.

Percy’s writings are becoming classics because of his portrayals of how we are “Lost in the Cosmos”—the title of his satirical 1983 “self-help” book. Having exalted the autonomous individual, surrounded him with vast material wealth, and then freed him from the bonds of tradition and religious belief, writes Percy, we are somehow surprised that “man’s confidence in the place of the self in the Cosmos” has declined. Despite immense freedom of choice, his protagonists rarely know how to respond to the world. When faced with a question, they frequently shrug and answer, “All right.” What caused this alienation?

Percy believed that modern science had diminished reality to the interplay of two elements: cause and effect. Translating this reduction into language, communication is limited to arbitrary signals and responses. And psychology and medicine repeat the pattern by restricting human interaction to the two elements of stimulus and response. The existentialist writers who appealed to the young Walker Percy realized that these approaches to knowledge left the human person homeless in the world and alienated from the self. Any meaning must be self-created through our intense consciousness of life experience, they wrote.

But two Christian existentialists, Gabriel Marcel and Søren Kierkegaard, helped Percy further along. Kierkegaard in particular led him to convert to Catholicism in 1947, for the Danish philosopher saw that modernity was treating the human person as a mere “specimen” rather than an individual. Percy soon realized that modernity’s reduction of knowledge to two elements was fundamentally flawed. A truly humane practice of language, for instance, involves a third term—the symbol, which cannot be reduced to a mere “signal.” And as Percy developed further, he saw that for interactions between two people to be humane, a third element must arise there as well—namely, a relationship.

Before the fictional physician Tom More begins his moral recovery in Love in the Ruins, he participates in the alienated “stimulus-response” pattern of modern medicine. He has invented a machine, the “ontological lapsometer,” which promises to eliminate alienation by readjusting one’s emotional state through electro-chemical adjustments of the brain. After the novel’s crisis, More ultimately accepts his own alienation as a permanent feature of his humanity and finds solace in a real relationship, namely marriage.

Having learned from his mistakes, More returns in Percy’s strongly plotted final novel, The Thanatos Syndrome(1987), in which the medical establishment has come to understand evil itself in cause-and-effect terms. Doctors deal with it clinically, justifying euthanasia, abortion, and the killing of infants up through 18 months, along with reducing human aggression by injecting chemicals into the water supply. In the moral center of the book, Father Simon Smith confesses his attraction to the passion, romanticism, and daring of an analogous mode of thought when he witnessed it among physicians in Nazi Germany during the 1930s. After talking with a doctor’s son, who plans to join Hilter’s SS as soon as possible, the priest admits, “If I had been German not American, I would have joined him.”

Clarity for Today (and Tomorrow)

Brian Smith’s book clearly shows how Percy’s political intuitions originate in his understanding of human relationships. I wish he had charted Percy’s “wayfaring” chronologically rather than thematically, for then his readers could see how a late work like The Thanatos Syndrome shows an ever-deepening understanding of the symbolic significance of relationships. Ignoring that significance has demonic consequences, Percy believed, and they are fully displayed in that novel.

The first step toward humanity in many of Percy’s books is to recognize our own capacity for evil. It’s a darkly satirical lesson, but unlike so many of today’s dystopias, it is also hopeful. By recognizing their capacity for evil, characters like Tom More and the priest emerge from the cause-and-effect, stimulus-response model for humanity. Evil is a “third thing” that becomes meaningful only in the context of true human relationships—and so is the good. Good and evil can be named only in the context of symbolic language, which in turn implicates us in a moral universe. And meaning for Percy is most clearly illuminated in relation to the goodness of the Logos, the ultimate “third thing” in any relationship.

Don’t look for happy endings in Percy’s novels. But you may find that his horror and hilarity clarify many of today’s cultural confusions. And like other classic authors, he’ll clarify tomorrow’s confusions as well.

Daniel Ritchie teaches English at Bethel University.