In this series

One of the world’s largest Christian denominations faces potential fracture as United Methodist leaders gather to finally decide how to navigate deep divisions over gay marriage, ordination, and ministry.

The United Methodist Church (UMC) meets Saturday through Tuesday to weigh options to address the differing convictions on the issue, including some that would lead one side or the other to leave the denomination.

This special session of its General Conference, a denominational decision-making body made of around 1,000 delegates, represents the culmination of years of passionate debate about the application of scriptural teachings, particularly when it comes to issues around sexuality.

There’s a lot at stake. Beth Ann Cook, a UMC minister and clergy delegate, said the issue comes down to “how we interpret and apply Scripture in our daily lives,” and she’s praying that “delegates fully and honestly face the depth of our divisions.”

“While this General Conference is about much more than LGBTQ justice and inclusion for the United Methodist Church, we are at this juncture because of the discrimination against LGBTQ people in the church,” said Jan Lawrence, whose Reconciling Ministries Network advocates for the UMC to change its longstanding policies and language around homosexuality.

Since its first official statement on homosexuality in 1972, the denomination has tried to mark out a middle ground of grace and traditional orthodoxy, stating that “homosexuals no less than heterosexuals are person of sacred worth” while still considering “the practice of homosexuality … incompatible with Christian teaching.”

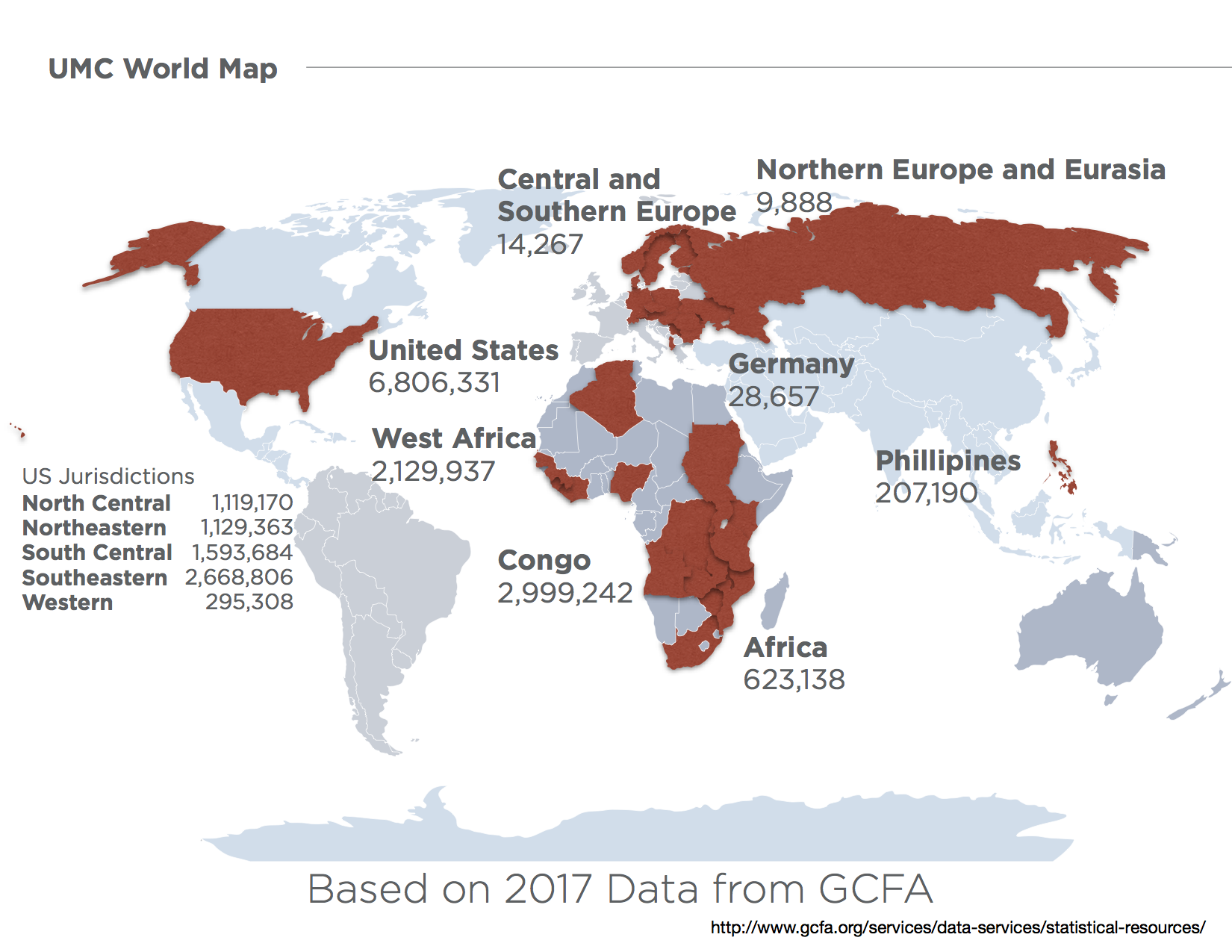

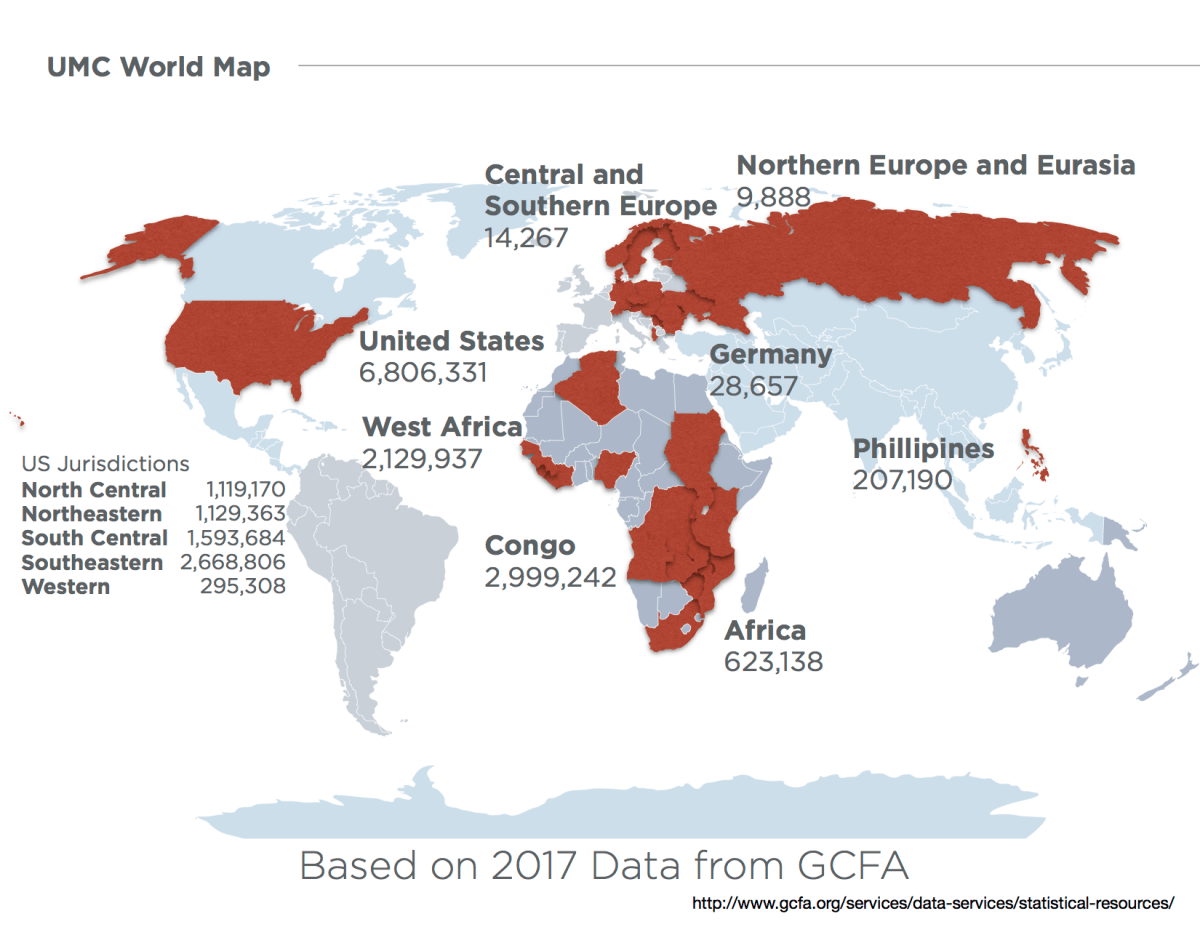

Decades later, with half the 12.5 million-member denomination located outside the US, the UMC’s historic position has become the source of heated debates at the General Conference gatherings, held every four years. The clashes have intensified as protestors eager to see the denomination change its stance interrupt deliberations and in one case, a demonstrator threatened to jump from a balcony.

This dissent has been going on for well over 20 years. By now, some pastors and bishops violate the prohibitions on same-sex marriage outright, and several regional bodies have chosen to ordain and commission openly gay clergy and a bishop.

Many in the United States consider the UMC a more progressive denomination, though they have officially held a more traditional position on sexuality, voting to add statements barring ordination for “practicing homosexuals” in 1984 and same-sex marriage ceremonies in 1996.

Though some American Methodists have shifted in favor of welcoming those in same-sex relationships, the American UMC’s numbers have experienced a consistent, gradual decline. Methodists’ traditional stance now stems from more conservative membership on the African continent, whose growth has outpaced the American decline.

Courtesy of Jeremy Steele

Courtesy of Jeremy SteeleBut even in the States, members are twice as likely to identify as “conservative-traditional” (44%) than “liberal-progressive” (20%), according to a denominational poll. After gay marriage became legal in the country in 2015, members of UMC churches in the US remained pretty evenly split on the issue, with 41 percent in favor of keeping the church’s ban on same-sex ceremonies and 42 percent against it.

If Methodists have been divided on this issue for so long, what’s kept them from splitting before? One factor holding the denomination together is its trust clause, which deeds all property to the regional body rather than to the local church. Because of this setup, any church that decides to leave the denomination loses its property (or must buy it back from the denomination).

More than 100 proposals related to human sexuality were brought up at the last general conference in 2016. After days of consideration, debate, and prayer, the church voted to table all resolutions related to the issue and instead called its bishops to appoint a commission to evaluate possible ways forward.

Over the next two years, the commission generated three plans as possible solutions, which delegates will review at a special General Conference February 23–26.

The “One Church Plan” removes prohibitive language from The Book of Discipline, the UMC’s book of law and doctrine, allowing regional bodies, churches, and pastors to exercise their own conscience on this issue. It adds language that permits UMC clergy to choose whether or not to conduct same-sex marriages, churches to choose to allow those weddings to take place in their sanctuaries, and regional bodies to choose to ordain LGBT clergy. It also adds language that ensures clergy and churches who make those choices will not be punished for them.

Mark Holland is a clergy delegate and executive director of Mainstream UMC, a group working to pass the One Church Plan. He says that “the One Church Plan gives a gracious place for both ‘conservatives’ and ‘liberals’ to be who they are for their mission fields.” This focus beyond the legislation to enabling diversity of mission and ministry is a central argument made by those supporting this plan.

The “Connectional Conference Plan” maintains an umbrella organization that will provide shared organizational needs like pension management and disaster relief while creating three branches that are split along ideological lines on human sexuality. In this plan there would be a progressive branch, a unity branch, and a traditional branch. Those new branches would decide on new names and function relatively independently of each other.

The “Traditional Plan” maintains the current stance against gay marriage and ordination, proposes enhanced accountability, and offers a gracious exit to those who feel they cannot in good conscience remain part of the denomination. Those bodies who leave would be given an exemption from the trust clause and allowed to retain their property. (In an early ruling by the denomination’s judicial body several parts of the original plan were deemed unconstitutional, and it has since been altered and will be presented as the “Modified Traditional Plan.”)

Going into this meeting, several lobbying groups have formed in support of various plans and drawn lines in the sand.

A group of evangelical United Methodists called the Wesleyan Covenant Association (WCA) represents the largest subset, with 125,000 people in 1,500 churches favoring the current, more traditional stance under the rallying cry of being committed to the “Authority of Scripture and the Lordship of Jesus Christ.”

Though they have not endorsed a single plan, they have been clear that if the One Church Plan were to pass, it “would be untenable and would force us to lead in the formation of a new expression of connectional Methodism.”

The WCA has appointed a group to begin working on everything needed to begin what would become a new Methodist denomination. “Our differences are irreconcilable,” WCA president Keith Boyette said. “Divisions within the UMC have led to missional paralysis and largely prevented the church from fulfilling its mission.” After the gathering in February, the WCA board will meet to decide whether or not bringing that new expression into existence at a convening conference for a new denomination will be necessary.

But a sizable number of Methodists have prioritized keeping the body together. Groups like Mainstream UMC and Uniting Methodists are lobbying for the One Church plan, which they say “holds the denomination together for the widest ministry with the most impact for living out the United Methodist Mission.”

Lastly, groups like the Queer Clergy Caucus, Affirmation, and Reconciling Ministries Network that say the One Church Plan is not progressive enough. Jan Lawrence is clear that “none meets our mission of affirmation and inclusion of LGBT persons in the full life of the church.” The UM Queer Clergy Caucus has offered an alternative to the three plans that resulted from the work of the Bishop’s Commission. Their “Simple Plan” removes “the language from the Book of Discipline that excludes LGBTQIA+ people from full participation in the church.”

All of those groups will converge in St. Louis, Missouri, where 864 lay and clergy delegates around the globe will come to a decision. The four-day meeting begins with an entire day in prayer and worship. The following day, the delegates will prioritize the various pieces of legislation to determine which proposals to move forward. The third day will be focused on refining legislation to be brought to a final vote and debate on the fourth and final day.

To that end, the denomination has issued a call to prayer asking “for God’s leadership to guide us effectively in fulfilling the mission of the church.”

“My request of God is for an inbreaking of his presence that returns our attention to proclaim the gospel as Christ,” said Joy Moore, senior pastor of Bethel United Methodist Church in Flint, Michigan, and the founding associate dean of Fuller Theological Seminary’s African American church studies center.

Some like Randall Miller, a lay delegate, say they “still hope for a fully inclusive United Methodism in which pastors, local, churches, and regional bodies can make their own decisions.”

Others like David Livingston hope to keep all sides at the table. “For a bird to fly it needs a left wing and a right wing. For the UMC to be faithful to its roots, we also need a left wing and a right wing,” he said.

In the midst of the passionate debate and some trepidation, there is a lot of hope for the UMC, with those on all sides sharing concern for the church’s witness and mission going forward. Or, in the words of Kansas pastor Mark Holland, that the outcome might “fully usher in the fullness of God’s grace in this world.”

Jeremy Steele is the teaching pastor at Christ United Methodist Church in Mobile, Alabama, as well as a writer and speaker. His most recent book is All the Best Questions.