In this series

Update (March 4): The head of the Southern Baptist subcommittee tasked with reviewing 10 churches for possible violations of denominational standards regarding abuse resigned on Friday, according to a Houston Chronicle report. Ken Alford cited “controversy and angst” over the bylaws workgroup’s response, but defended their position, saying their small group was not equipped to investigate the churches further.

———–

Conflicting statements from Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) leaders on the denomination’s approach to addressing sexual abuse have left victims, advocates, and pastors themselves with a sense of whiplash—and called into question the fate of proposed reforms to improve accountability among SBC churches.

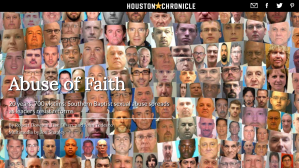

Those concerned about abuse within America’s largest Protestant body—including the hundreds of cases reported by the Houston Chronicle and San Antonio Express-News—cheered repentant statements and bold plans for policy changes from SBC president J. D. Greear last week, only to see his recommendations largely turned down by part of the SBC’s Executive Committee days later.

Greear called on the Executive Committee (EC), the decision-making body tasked with addressing convention business between annual meetings, to take a harder line against churches that mishandle abuse allegations. Specifically, he wanted the SBC to look into 10 particular churches implicated in the recent investigation to see if the churches still meet denominational standards.

Though Southern Baptists have generally resisted top-down oversight, several prominent SBC leaders, including Greear and Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission president Russell Moore, had begun to say that a commitment to church autonomy could not supersede their responsibility to prevent and address abuse.

But when it came to the 10 churches in question, the executive committee’s bylaws workgroup declared that 7 did not have credible claims of wrongdoing to investigate in the first place, reasoning that the churches didn’t merit further review and admonishing SBC leaders against calling for inquiries without criminal convictions and evidence that churches had knowingly permitted predators in their midst.

“I am deeply grieved at the SBC EC response to JD Greear. The EC has demonstrated the exact problems that lead to the abuse of so many—whitewashing the crimes and coverup, choosing largely irrelevant criteria, and investigating issues they have no training to investigate,” tweeted Rachael Denhollander, an attorney and victims’ advocate who was appointed to an SBC presidential advisory group tasked with studying its response to abuse.

“JD Greear and some leaders have been seeking expert/survivor help and moving forward with firm first steps to change. The EC has undermined and destroyed that effort. I hope these mistakes are due to lack of learning and that they will withdraw, seek help, and remedy these errors.”

After a two-day meeting, the six-person EC subcommittee released a statement last Saturday tempering Greear’s charge. “The Convention, through its Executive Committee, should not disrupt the ministries of its churches by launching an inquiry until it has received credible information that the church has knowingly acted wrongfully,” the subcommittee concluded.

“Although the overwhelming majority of sexual abuse cases remains tragically unreported, in virtually all reported cases, the abuse and cover-up of abuse were criminal acts undertaken by a few individuals within a church,” the group wrote. “The church body rarely knew about these actions and even more rarely took any action to endorse or affirm the wrongful acts or the actors themselves.”

(The three churches the workgroup deemed to require further inquiry included Sovereign Grace Church in Louisville, where concerns of abuse coverup have swirled around former Sovereign Grace Ministries president C. J. Mahaney for years.)

Their remarks sent waves across the SBC, including among fellow members of the executive committee who hadn’t been involved in crafting the response.

Ed Stetzer, executive director of the Billy Graham Center at Wheaton College, called out the bylaws workgroup for hasty decision-making and an “arbitrarily high standard for inquiry.”

“Assessing these situations typically takes months or, in some cases, years. Now, suddenly, a Baptist committee is able to consider six churches in just over 24 hours and declare them all open and shut cases?” wrote Stetzer, former president of LifeWay Research. “You can see why some may not feel that due diligence was done.”

At least three EC members spoke up online to decry the workgroup’s statement and pledged to advocate for victims before the denominational body: EC vice chairman and California pastor Rolland Slade, Florida pastor Rick Wheeler, and Texas pastor Jared Wellman, who tweeted, “I am a member of the EC who supports @jdgreear’s “10 Calls to Action on Sexual Abuse,” and I want to make sure sexual abuse victims’ voice is heard regarding the recent Bylaws Workgroup report.” They fielded emails from SBC abuse victims about their experience and recommendations for improvement.

After condemned the EC statement for “undermining efforts” and “dismissing coverups and abuse brought to light,” Megan Lively said she appreciated Wellman for hearing out stories like hers.

Lively came forward last year to recount how Southern Baptist leader Paige Patterson discouraged her from reporting an alleged instance of rape while she studied at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary; Patterson was later fired from his post as president of another SBC seminary.

The bylaws working group statement reflects the concerns of SBC leaders who don’t want to see the convention come to hasty conclusions or presume guilt after every allegation, which they say would be “untenable and unscriptural.”

The voices critiquing the statement want to see an approach that centers more around the victims—trusting their stories and enabling them to come forward so abuse can be addressed.

“The SBC EC has bowed to political expediency over biblical principles in their hasty & unwise decision to minimize & marginalize & reenact the pain of the victims, in order to assuage the wrath of the accused, alleged violators,” wrote SBC pastor Dwight McKissic. “Same mindset undergirded slavery/Jim Crow in SBC.”

Dean Inserra, a member of the ERLC leadership council, quipped: “SBC EC, I’ll help you out real quick with a new response to President Greear’s calls to action: ‘Whatever it takes.’ Try that.”

The unpopular response to Greear’s recommendations reflects differing philosophies within the denomination over whether or how the SBC could improve its response to abuse. Such a split would challenge whether new policies go forward, including a proposed amendment to explicitly call out churches that harbor abuses as grounds for disfellowshiping. (It has to be approved two years in a row to be ratified.)

As the Twitter account SBC Explainer wrote:

The amendment will now go to the Messengers for consideration. The debate will ensue. The Convention will act according to the messengers. What we do in years to come will in large part depend on who shows up, debates + votes this, and votes for president in years to come. #SBC19

Lastly, it really can’t be understated how possible it is that the Convention fails to pass any amendment whatsoever. The 2/3 vote is a purposefully high threshold. What a shame on us all if we fail to act at #SBC19. Public debate needs to start. We need to get on the same page.

Other recommendations from the advisory group appointed by Greear include urging churches, associations, state conventions, and entities to strengthen abuse policies; considering background checks for SBC appointees; and weighing the possibility of a database of offenders.

ERLC executive vice president Phillip Bethancourt, a member of the group, praised the Baltimore Baptist Convention this week for approving $25,000 to fund “free criminal and sex offender background checks for every church in our association during the calendar year 2019.”