Years ago I sat alongside a dozen pastors in a sun-baked, mud-caked church in rural northern Mozambique. They’d gathered to test a recent translation of Isaiah in Lomwe, their local dialect. The Isaiah passage was familiar to me, but not the language. Still, as we went around the circle—each pastor reading aloud to hear how the new translation sounded—I picked up enough to pronounce some words. When it came my turn to read, rather than pass, I plunged in and read a few verses myself. The Lomwe pastors heard me speaking their language even though I didn’t fully know what I was saying. They beamed with delight. A white American minister had traveled all the way to their village to understand them without insisting they first understand him.

I can’t help but connect this experience to the first Christian Pentecost. In the wake of Jesus’ ascending to heaven and the Holy Spirit’s descent, Acts 2 reports new-and-improved Aramaic-speaking apostles speaking the gospel in the wide array of languages to the peoples gathered in Jerusalem (2:4). The crowds heard their own native tongues being spoken even though the apostles didn’t know the dialects (2:6). This is why we refer to Pentecost as a miracle of speech. But what if it was just as much a miracle of hearing?

I counted on such miracles most Sundays in my many years as a preacher. After a sermon, a listener would thank me for saying “just what I needed to hear.” When I asked what it was that I said, the person would relay the words they heard—words I knew I never spoke (being the manuscripted preacher I am). This was the Holy Spirit’s doing, I believe, making my words work in ways I hadn’t dreamed they would.

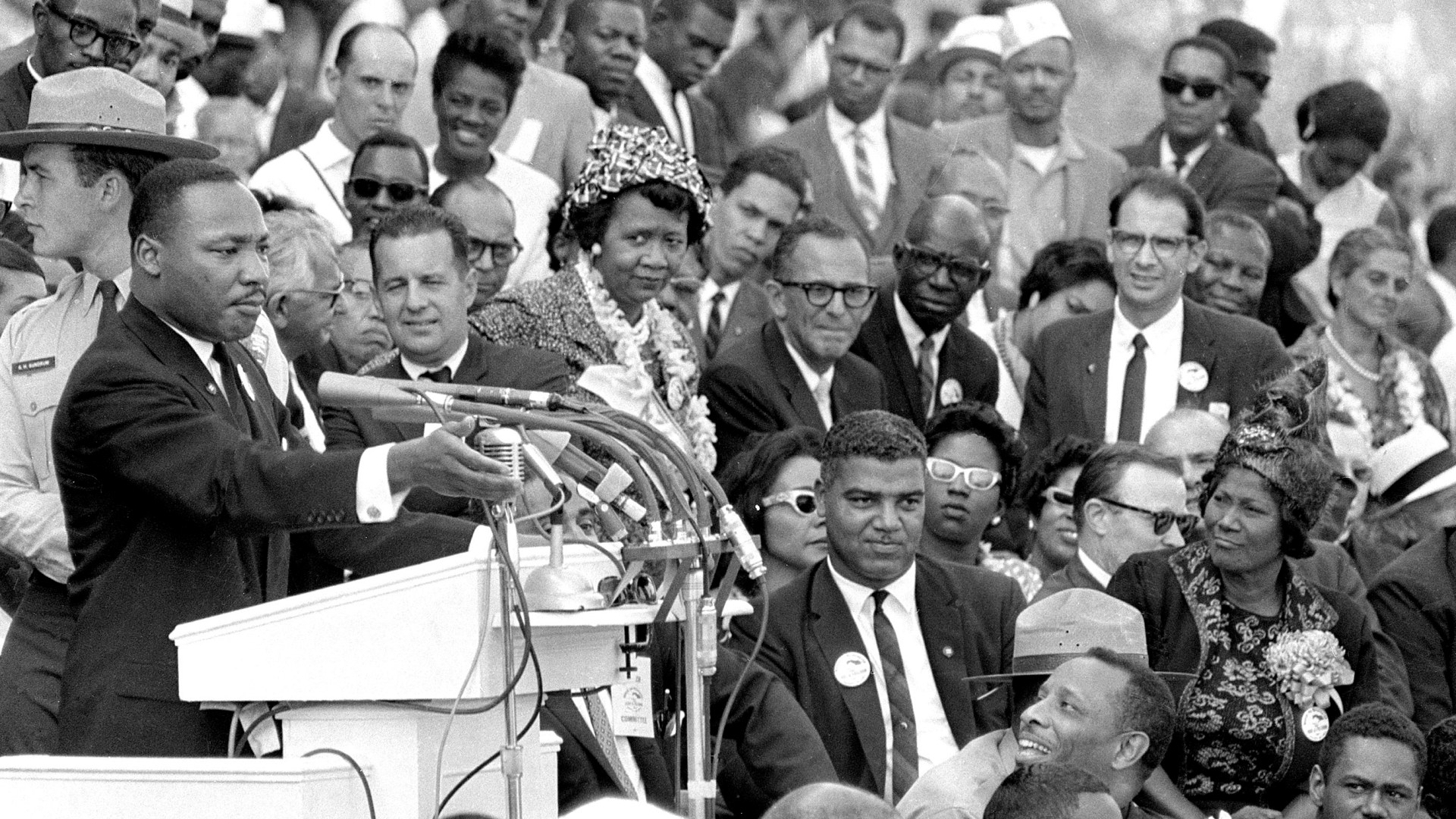

On this day devoted to dreams, specifically Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream of a country no longer divided by race, we need more hearing miracles. It is hard to listen when everything worth anything quickly becomes polarized. Ideas to be discussed give way to identities to be defended. There’s so much anger. Cable news and social media, late night talk shows and websites, arguments around family tables over the holidays, broken friendships and marriages, all of it fueled by fury bordering on the righteous.

Anger can be righteous. Anger concentrates passion, gets attention and conveys information fiercely and faster than any other emotion. We have it on record that Jesus got mad—at hypocritical Pharisees, at temple moneychangers, and at a fruitless fig tree. Old Testament prophets from Moses to Malachi let loose against the Israelites constantly. The psalmists shook an angry fist at God. There’s plenty of injustice and wrong in our world to get mad about. I get angry. So do you. A lot of you will get angry at me. Anger forces us to attend when we’d prefer to avoid. But for anger to achieve any righteous purpose, it has to eventually cease. The Spirit gives ears to hear, but at some point we must shut up and listen.

The arc of the gospel bends toward reconciliation. This is its beauty. We disagree and debate, but we do not divide. The love of God compels us toward oneness in Christ. The miracle of hearing makes room for mercy.

If you know anything about biblical Hebrew, you know it doesn’t contain vowels. You have to hear it spoken to know what it means. A group of rabbis later added dashes and dots to help readers distinguish one consonant word from another. Shift a few dots and the Hebrew word mercy is the word womb, a deliberate connection to connote how mercy links to the ferocious devotion mothers feel for their children, along with the pain such devotion entails. Scripture often compares the passion and pains of childbirth to God’s own love and mercy. (On the other hand, if you rearrange the dots another way, the word mercy becomes the word vulture, proving once again how easy it is for human passions to pervert.)

As Christians, we hang crosses on our walls and around our necks to remind ourselves how mercy is nonnegotiable. Jesus died on a cross for our sins and we didn’t deserve it. Theology labels the cross the passion of Jesus, a righteous anger that’s righteous because it bends toward the reconciliation of all things, a fierce power that taps into long-suffering, motherlike mercy for the cause of new birth.

It takes practice to live under the Cross. On Sundays in many churches, Christians greet one another by “passing the peace” during worship—every introvert’s nightmare. It’s a practice that reaches back centuries because peace and reconciliation take practice. The idea is that if you show up at church mad at your neighbor, you get to leave in peace. Do it enough and you become peacemakers, whom Jesus blesses and calls children of God.

It’s not enough to go through the motions, however. Jesus says it has to come from your heart (Matt. 18:35). Anne Lamott compared faking grace to drinking rat poison and then waiting for the rat to die. Martin Luther King Jr. called it “adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars.”

My wife, Dawn, and I didn’t agree about everything. Most married people don’t. We got angry and argued and fought, but at the same time stayed committed to trying to listen and understand and make up. We always did this in front of our daughter because she needs to realize it’s okay to get angry as long as the energy finds resolution. The same is true for Christians whenever we find ourselves in conflict, whether with our neighbors or enemies. In Christ, we cross whatever divides even if it kills us to do it—which is sometimes what it takes.

As a minister, I would read and experience firsthand what my hometown newspaper labeled “the unchurching of America.” I get it. Who wants to hear you’re not always awesome, but instead a sinner who still needs salvation and who needs to forgive and make peace and not let the sun go down on your anger? Who wants to hear how God loves you and shows you mercy so you can go and do likewise? We’re taught as Christians to know nothing more important than Jesus Christ and him crucified on a cross for our sake (1 Cor. 2:2). But it takes a miracle to hear this. Grace is offensive. To forgive is an outrage. Reconciliation feels like a death sentence and a sure admission of weakness. Mercy hurts like a mother. And yet, “blessed … are those who hear the word of God and obey it” (Luke 11:28).

Daniel Harrell is editor in chief of Christianity Today.