The line that forms Saturday mornings outside The Father’s Heart Ministries stretches farther than it used to—in part because of a rising number of first-time guests at the soup kitchen in Manhattan’s East Village, and in part because masked patrons stand safely distant from one another.

With the highest unemployment numbers since the Great Depression, food pantries across America are experiencing an average of more than 50 percent growth in attendance, with two in every five people seeking assistance for the first time.

But also growing at ministries like The Father’s Heart is the number of volunteers who want to serve. In an era when many food pantries and soup kitchens are suspending services due to coronavirus-related precautions, the volunteers have kept the 22-year-old food program operating out of the historic brick-and-stone church building that houses it. In fact, there’s a waitlist to serve there.

Churches have long played a critical role in America’s food pantry network, particularly in areas with glaring hunger needs. And amid the COVID-19 pandemic, they’re continuing to do what they’ve always done—now with the help of a new wave of volunteers, particularly younger ones who find themselves home from school and work, according to Jeremy Everett, executive director of the Baylor Collaborative on Hunger and Poverty at Baylor University.

“A part of our faith tradition is to love our neighbors as ourselves,” Everett said. “If you have a church community, and maybe some of the traditional volunteers that don’t feel like it’s safe to volunteer, that elicits other people to step up.”

Marian Hutchins is the executive director of The Father’s Heart and one of six pastors at the ministry’s host church, which bears the same name. As volunteers arrive, she smiles behind a mask and welcomes them with a “Good morning!” and a “How was your week?”

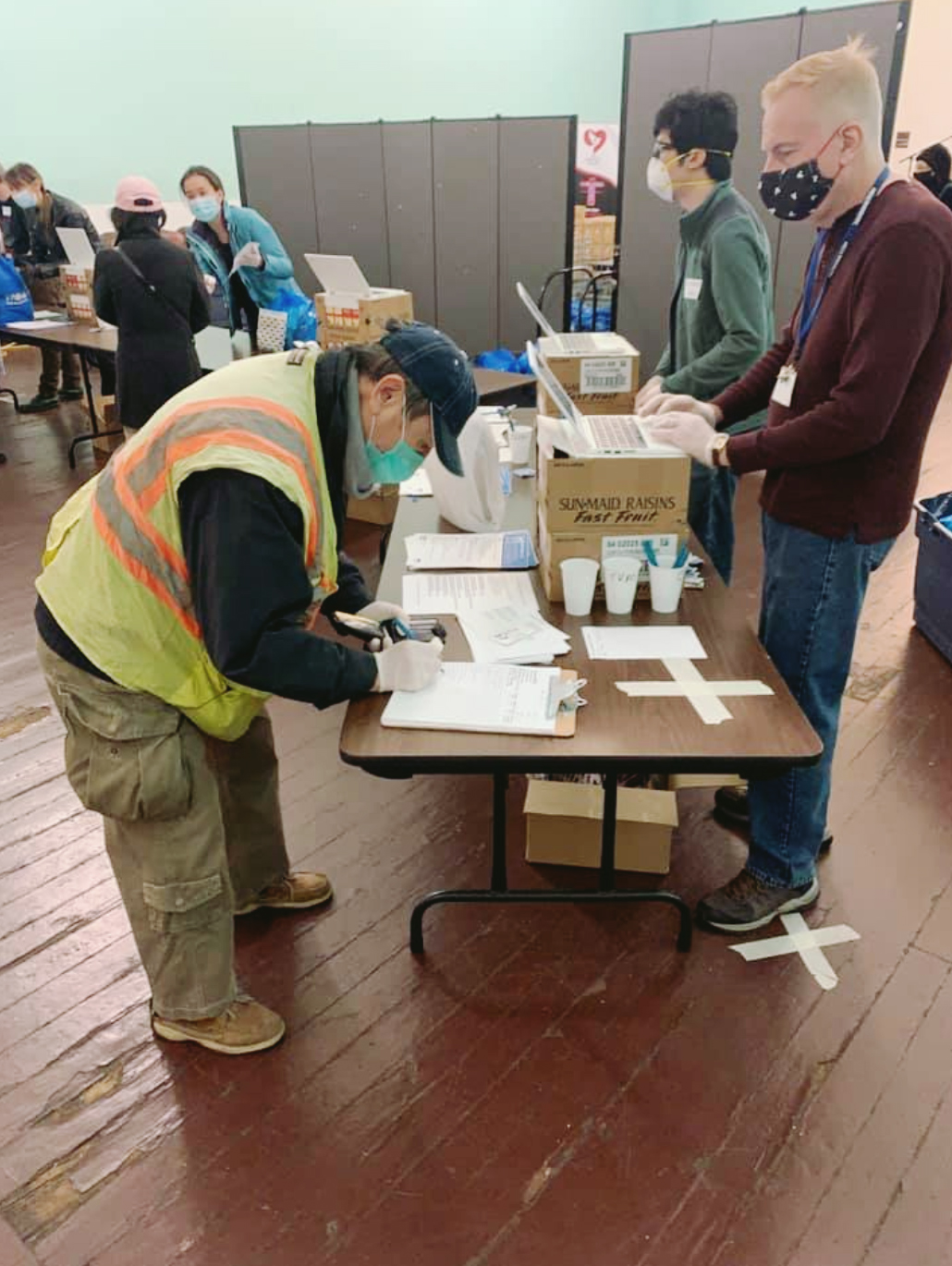

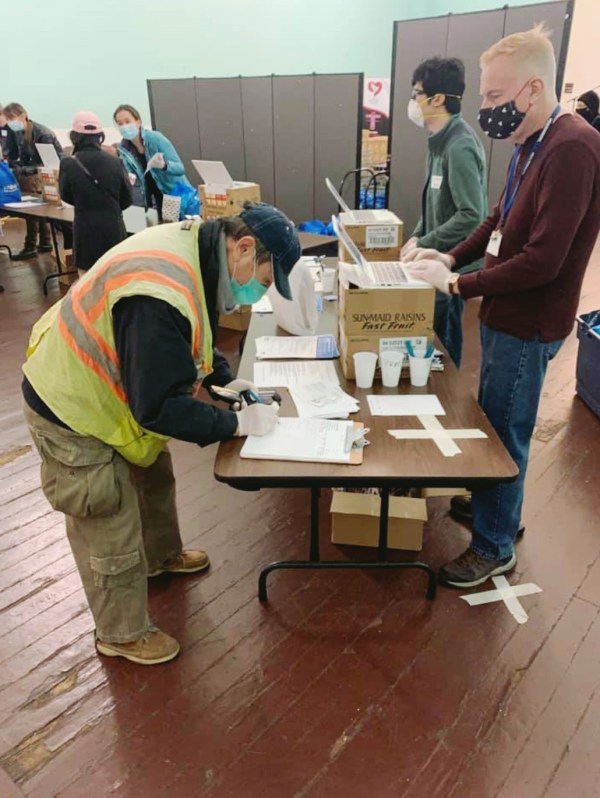

In normal times, Hutchins would add a hug to her greeting, but now volunteers immediately wash their hands once they arrive and don masks and gloves. They can’t serve otherwise. And in usual times, as many as 150 volunteers would descend on the church on Saturday morning to hand out food and run a full-service kitchen. But now, with social distancing requirements, only 30 volunteers are allowed at one time.

The volunteers flock in from across New York City. Some have been coming for close to a decade, like Katie Sullivan, who stumbled on The Father’s Heart in 2013 when a friend told her the soup kitchen was short on volunteers.

Courtesy of The Father's Heart Ministries

Courtesy of The Father's Heart Ministries“I just fell in love with it immediately,” said Sullivan, an anti-corruption attorney for The World Bank who now avoids the subway and walks four miles each way between her Brooklyn apartment and the church. “Their focus on maintaining people’s dignity and really caring for people, and the way that they do table service, really lit up my heart.”

Not only do volunteers continue to show up every Saturday, they’re also reaching into their pockets.

The Father’s Heart typically has a yearly budget of around $1 million. But Hutchins says they’ve had an increase in private donations and grants from volunteers, long-time supporters, church partners, and organizations like United Way and Hope for New York. The availability of the CARES Act small business loans has also buoyed funding hopes at The Father’s Heart and pantries across the country.

While non-perishable foods like rice and canned tuna are staples of the pantry bags guests receive, Hutchins said the additional funding will help them “take it up a few notches” and order the kinds of fresh foods she buys for her own family, essentials like eggs, milk, grains, and meats.

On a recent Saturday, Hutchins felt something different from the moment she woke up in her Flushing, Queens home. With all the strict protocols she’d put in place, she realized, the atmosphere during the Saturday food program had become flat. City-mandated protocols had drained so much of the human contact from the operation.

To create more separation between volunteers who prepare groceries, Hutchins had moved the food pantry staging area from a tighter space in the basement to the 3,600-square-foot sanctuary, which was vacant since Sunday church services had moved online. A weekly sit-down, buffet-style breakfast was replaced by “breakfast to go,” where volunteers pass ready-to-eat packed food through an outside window and give guests a second bag of groceries inside the building.

A service that once beamed with hugs, handshakes, and praying hand-in-hand has been subdued to a monotonous assembly line.

“It’s hard with the six-foot distancing,” Hutchins said. “It’s changed the dynamics in the sense that the guests can’t stay long, they can’t get close.”

She felt God telling her the volunteers needed an extra boost of inspiration. So on this morning, instead of handing out cook and server assignments for their restaurant-style soup kitchen, Hutchins gathered her 30 volunteers in the high-ceiling sanctuary and opened with a Scripture reading and a prayer.

She read from Psalms 46: “Be still and know I am God.”

Although Hutchins, who is 64, is ordained and has served in this church for 36 years, she would not usually have this kind of spiritual component for volunteers. But in truth, she was looking for inspiration, too.

Standing at the center of the elevated alcove altar, an old wooden cross draped with red velvet cloth hanging atop, she looked out to her volunteers and prayed:

“Lord, let us see and let us feel. Let us be your hands and be sensitive, be present and not just get through the safety of today but let’s be present.”

She finished the prayer with:

“Let us be present with your knowledge and be alert to people’s needs.”

Hutchins’ prayer was met with echoing “Amen!” and “Hallelujah!” from volunteers spread every six feet throughout the teal-walled sanctuary on white-taped floor markers.

After the prayer, some volunteers went back to prepping food pantry bags. Others assembled to-go breakfast packages full of cheerios, milk, juice boxes, granola bars, yogurt, and chicken salad. They added lollipops and Cheez-Its for kids. And, of course, individually wrapped wipes.

Not long after Hutchins finished her prayer, the doors opened and guests started to roll in 30 to 50 at a time, staggering their entries and exits. Since New York City became an epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic, the operation has been opening an hour and a half earlier than normal to accommodate the extra safety logistics.

“Everything has got to be strict,” Hutchins said. “But we find ourselves grabbing an arm or an elbow or pat someone’s back. It’s so hard to stay sterile when you see people you love and you want to reach out to them.”

The pantry serves just over 400 guests on a given Saturday, though Hutchins knows that many of the older regulars are staying home out of caution, even as the pantry registers a growing number of new guests each week.

Courtesy of The Father's Heart Ministries

Courtesy of The Father's Heart MinistriesThough guests remain thankful, some have met the changes with sneer.

Shortly after opening, a lofty, striking homeless man questioned the volunteers’ faith when he saw them wearing face masks and gloves and keeping their distance.

“Why?” he asked loudly, pointing to their protective gear. “Don’t you believe in God? Don’t you have faith?”

“It’s not about my faith,” Hutchins, her petite frame drowning in an overcoat, tried to lull the man’s taunts. “It’s about other people getting my germs.”

“Jesus touched the lepers, and he didn’t get leprosy,” the man retorted.

Another homeless man was on his way out when Hutchins offered him a mask. He quietly refused, saying, “I have faith in God.”

Still, Hutchins emphasizes, such encounters are one-offs. Most of their guests are embracing the challenges with gratitude. One homeless woman smiled and told her, “You doing this brings hope to everyone on the streets.”

Guests are normally offered a Bible as they leave the church. In the past, many would refuse. But lately, Hutchins says, guests have been taking Bibles like “crazy.”

“People are saying, ‘Everything that I counted on, everything that I lived for, everything that I relied on is gone,’” she said. “I think that causes people to look away from the natural things and look to God.”

What is hard is that Hutchins and volunteers can’t console hurting people in the same ways they used to. The comfort that hugging and physical contact bring are what some of the guests and volunteers had come to look forward to, said Neil Weiss, a former homeless guest who now serves as a volunteer supervisor.

“We can’t interact like we used to,” Weiss said. “But, we still hear them say ‘God bless you. We really appreciate it.’ We heard that before, but it seems like they’re expressing it deeper.”

Volunteers are finding ways to adjust. For example, since sitting down with guests to eat and mingling with them in line are no longer options, they’ve turned to a new initiative in the form of prayer slips. Guests write prayer requests on pieces of papers that volunteers then carry with them throughout the week and pray over. The prayer pens are sanitized after every use.

Food insecurity is usually linked to the homeless. But since the pandemic hit and unemployment has soared, Hutchins says The Father’s Heart is seeing more than 100 new guests almost every week. Many of these first-timers have never before had to find free food.

“Who knows that there’s a Food Bank for New York City unless you need food?” Hutchins said.

New guests she’s encountering are going online and calling hunger hotlines to find resources they’ve never needed before. Many come agitated, scared, or confused.

And they’re very hungry. Hutchins says she’s proud that The Father’s Heart is equipped to remain open with staff and supplies for the long haul.

Courtesy of The Father's Heart Ministries

Courtesy of The Father's Heart MinistriesOver 100 service locations affiliated with the Food Bank for New York City—which supplies more than 1,000 food pantries and soup kitchens—have suspended their operations. According to New York City Mission Society, an organization aimed at ending multigenerational poverty, a third of the nation’s food pantries are also closed, impacting over 17 million people.

Some pantries don’t have enough space to comply with social distancing requirements. Some experienced debilitating drops in volunteers.

“We didn’t have volunteers to cook anymore,” said a representative from Community Help in Park Slope Inc., a similar service center in Brooklyn that recently suspended services. “Everyone is afraid to come in.”

Hutchins says she’s grateful to her volunteers for their dedication to serving the community. She worries about protecting their safety, too, every time she thinks about them leaving their homes and risking their lives to serve.

“You want to do what’s best for the community,” she said. “But you also have staff that you need to protect and take care of, too.”

To that end, Hutchins has had a lot of help. Partners in New York, such as the Food Bank and United Way, have provided boxes of gloves with every donation delivery. Masks have come in from church partners and locals around the city and across the country.

Ione Parshall is a retired military officer in Manhattan, Kansas, who wanted to help America’s “worst-hit city” that happens to share a name with hers. So far, she has rallied her congregation, University Christian Church, to make and donate more than 350 masks to The Father’s Heart.

“I just felt like I needed to do something,” Parshall said. “As a Christian, we’re supposed to reach out to those in need.”

Hutchins is now looking ahead to recovery. Her community has gone through similar crises, like Hurricane Sandy, and she wonders how people will overcome this one.

“There’s going to be a lot more people needing food,” she said. “We may have to be open more and hire more people.”

As they said goodbye to their last guest of the day, Hutchins offered individually wrapped Communion for her volunteers and closed with a prayer, which included:

“We are an extension of God’s love on earth.”

Then, in the middle of the sanctuary, pantry boxes stacked high around, and everyone standing six feet apart, they sang “Amazing Grace.”

Rita Omokha is a freelance journalist based in New York City. She is an alumna of Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.