It’s a Sunday evening and we’re just kids—black kids, in fact. We should be outdoors in fading daylight, slurping Mama’s homemade ice cream, catching fireflies, watching our parents laugh with neighbors, changing the record player—turning it low to soft-serenade our long-running, after-church meal.

Instead, dinner’s over and we kids are back at church. And get this: We kids are happy about it. “Sit next to me,” a friend whispers, pulling me over to her. We compare the outfits we’ve worn. Our summer sandals. Our straw summer handbags. As the boys come in, we try to act aloof, as if we don’t care. One boy pulls my friend’s curly ponytail. She starts to protest, but in walks our teacher.

“Let’s turn to Genesis.”

That’s our Bible leader, our Mr. Bell, starting a Sunday evening class for teens at the Cleaves Memorial CME Church in northeast Denver. It’s the Jim Crow ’60s, and this church is our heart place—our safe house sanctuary—in our red-lined cow town. We’re far from our parents’ Southern birthplaces and Dixie traumas. Yet we all have Bibles. White leatherette among the girls. Grown-up black among the boys. (Or a pew Bible if you forgot to bring yours.) For all of us, our Bible is something we don’t hold loosely—it’s something, indeed, to grasp, chew, swallow whole, and inhale, as if our lives depend on it.

Our lives do. We are black, and the wrong against us is a scourge and it’s sin. A toxic cocktail of lies and fears, the hurling mix of madness intends to kill us, again and again, every American day. When just leaving your home could mean risking your own death, your daily life can approximate a nightmare—never safe to fully wake up, never calm enough to exhale.

Thus, in almost every African American house, duplex, apartment, motel room, or trailer sits a Bible—often open, underlined, quoted, and being read. That was true for my generation, and it’s still true after all these years. The reasons aren’t confusing.

Survival

We need a raft, and the Bible doesn’t sink. We need an anchor, and the Bible holds fast. We need a lighthouse, and the Bible dares shine.

Even a silly teenager somehow knows that. There is a “ways and means” to the Book, with its Old Testament laws and New Testament grace. With its scandalous, audacious, paradoxically lovely Jesus and a rampart of parables and prophets, proverbs and psalms, kings and battles, family dramas, epistles, prayers, stories, and songs.

It was the book, as I had noticed, where black people are “dark … yet lovely” (Song 1:5) and Jesus himself, in John’s vision, is described as one with hair “like wool” and feet “like burnished bronze” (Rev. 1:14–15, ESV). In that Holy Book, indeed, this Savior Christ defies convention and narrow-minded fear. And in it, coincidentally, underdogs win.

“Let’s turn to Exodus.”

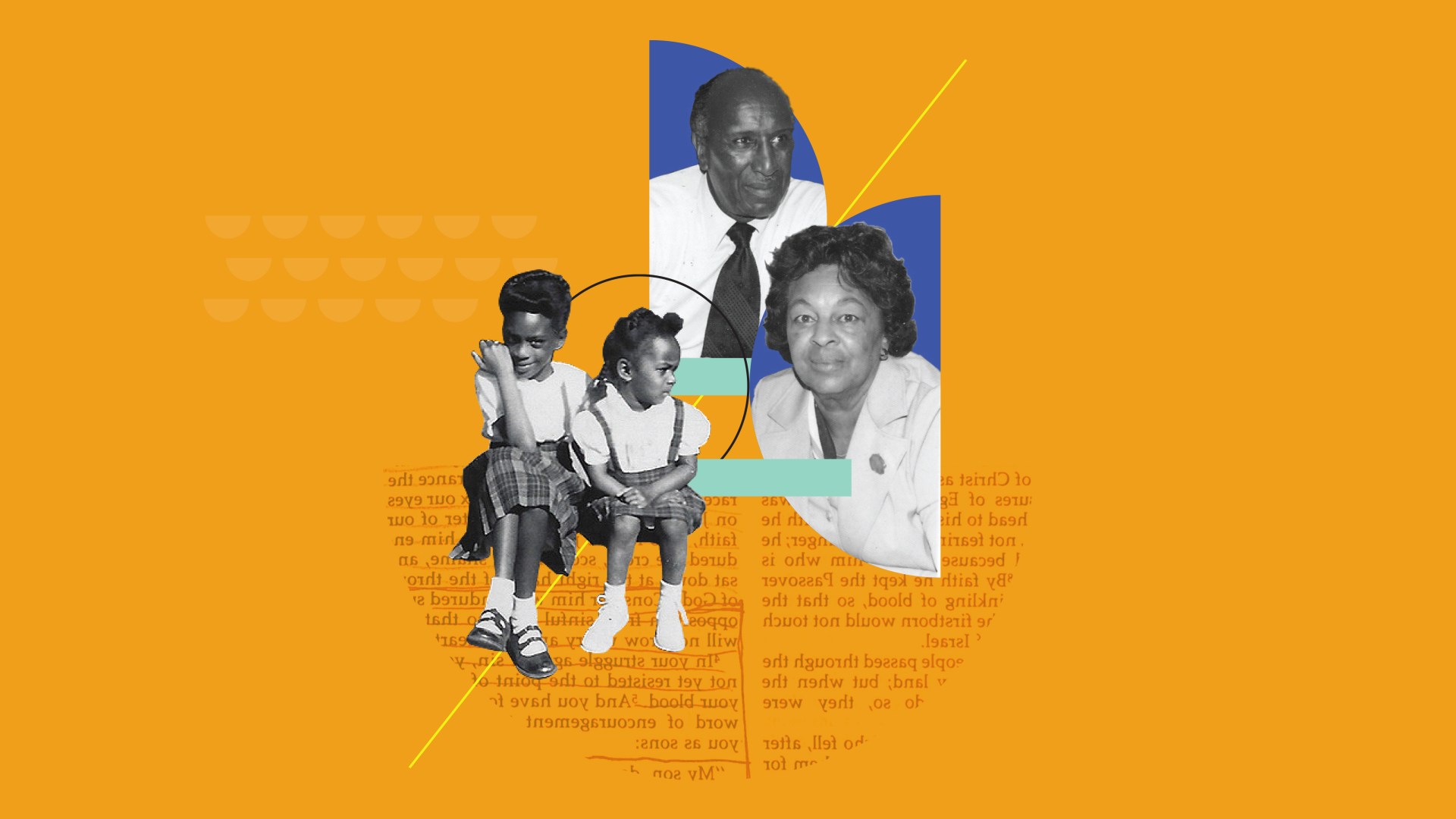

Courtesy of Patricia Raybon

Courtesy of Patricia RaybonMr. Bell had come up with his wife and children from Texas or Alabama or Mississippi or one of the places from which harassed and weary black people fled. A veteran of World War II, he’d served a country that refused him at every turn. But by persistence—and with the kindest heart we’d ever known—he became the first black person in our city hired by the downtown Woolworth’s store to be a floor clerk.

They assigned him to the basement floor. But it was a job, and he wore a shirt, tie, and Sunday slacks every workday. We respected and even loved him. He taught us of Christ, how the Lord redeems evil. So we’ll overcome this, Mr. Bell promised. Modeling that, he then began to teach.

“Let’s turn to Deuteronomy.”

Why does a grown man teach Bible stories? Why do his fidgety students listen? Those stories taught us how to survive our racial tsunami, creating for us a “black sacred cosmos,” as scholars C. Eric Lincoln and Lawrence H. Mamiya described the insulation that God’s Word builds for black souls against supremacist assaults.

The Bible was our love letter from God, drawing us to him, lifting us together. Indeed, if you were black and in church—which was pretty much every black man, woman, boy, and girl I knew—at some point, you were called on to study and teach a Bible lesson. Moreover, your effort was encouraged by the church: “Teach, baby!”

The Bible endorsed our personhood, and through it, we endorsed one another in turn. The world outside rarely did. It was dangerous, therefore, this book—especially for a disempowered people. Consider the “Slave Bible,” displayed in the Museum of the Bible in Washington, DC. It was published by missionaries “for the use of the Negro slaves.” For fear of inciting rebellion, this “Bible” omits Scripture’s stories of heroics and freedom. Moses, for example, is barely mentioned. “You’ll see a jump from Genesis 45, and they’ve cut out all the material to Exodus 19,” said Anthony Schmidt, associate curator of Bible and religion in America at the museum. In fact, “about 90 percent of the Old Testament is missing [and] 50 percent of the New Testament,” Schmidt told NPR. “Put in another way, there are 1,189 chapters in a standard protestant Bible. This Bible contains only 232.”

But the whole Bible? Given and studied in full, it’s revelation power.

“Let’s turn to the Book of Jonah.”

Hope

Courtesy of Patricia Raybon

Courtesy of Patricia RaybonScholars make much of African Americans’ love of Scripture and our common belief in the Bible’s stories as literally true. But at my Bible study, we never debated whether the story of Jonah and his whale was true or not. Instead, our focus was on celebrating Jonah’s story because, as with the entire Bible narrative, it gives drowning people life and a second chance.

Mr. Bell invited us into the big-whale story (among others), helping us unravel Jonah’s ordeal—we were humbled to learn God expects obedience and good ministry from his followers. Yet, if we fail, even in a storm, God grants another try—giving living hope. In the belly of the Bible, indeed, hope happens—especially in storms.

As storm-tossed people, we still cling to this uplift. But we cling also to God’s radical truth: that love and justice are both divine. Mr. Bell wanted us suited up, our life jackets sound. Thus, he taught us the whole affirming Book: how to read it, who the people were, why the wars were waged, how the Psalms were composed, what the parables meant, how disciples acted—indeed, who Jesus is and who we are in him.

We are loved, Mr. Bell insisted. Made in God’s image. Our salvation secured by a Savior who endured black-like shame on a rugged, government cross.

This was spiritual formation while our world was on fire. The truth of God’s Word held us aloft, in defiance of flames and smoke. Today, I still ride this updraft.

But beyond empowerment, God’s Word is also grounding, humbling. For me daily, it also teaches love. Consider him, indeed, taught Mr. Bell, “who endured such opposition from sinners, so that you will not grow weary and lose heart” (Heb. 12:3). I clung to this word during our Jim Crow crucible, and I still do—still stunned by its assurance.

“So, turn to Second Timothy.”

Mr. Bell adored that epistle. The imprisoned, aging Paul encouraging a young pastor. I still treasure the letter today. As it says, all Scripture is inspired by God, equipping us thoroughly “for every good work” (2 Tim. 3:16–17). Especially when life is hard. So it is true: More than other groups, black Americans still dive deep into the Word. It’s our lifeline. But during these times, decades later, I can almost hear Mr. Bell urging this: Dive with us.

Patricia Raybon is a regular contributor for Our Daily Bread and (in)courage. Her books include My First White Friend: Confessions on Race, Love, and Forgiveness and Undivided: A Muslim Daughter, Her Christian Mother, Their Path to Peace.

This article is part of “Why Women Love the Bible,” CT’s special issue spotlighting women’s voices on the topic of Scripture engagement. You can download a free pdf of the issue or order print copies for yourself at MoreCT.com/special-issue.