I will never forget the day I stood on the ruins of a third-century synagogue in Capernaum, just a stone’s throw from the beautiful blue waters of the Sea of Galilee. I was leading a tour of Christian pilgrims. Our guide called our attention to Matthew 23:3, a verse I had read hundreds of times but which now suddenly jumped off the page: “You must be careful to do everything [the teachers of the law and Pharisees] tell you.”

I was shocked. How could Jesus have recommended the teachings of the Pharisees when he warned against their hypocrisy in the same verse (“But do not do what they do, for they do not practice what they preach.”)? How could I have missed this recommendation during decades of serious Bible study?

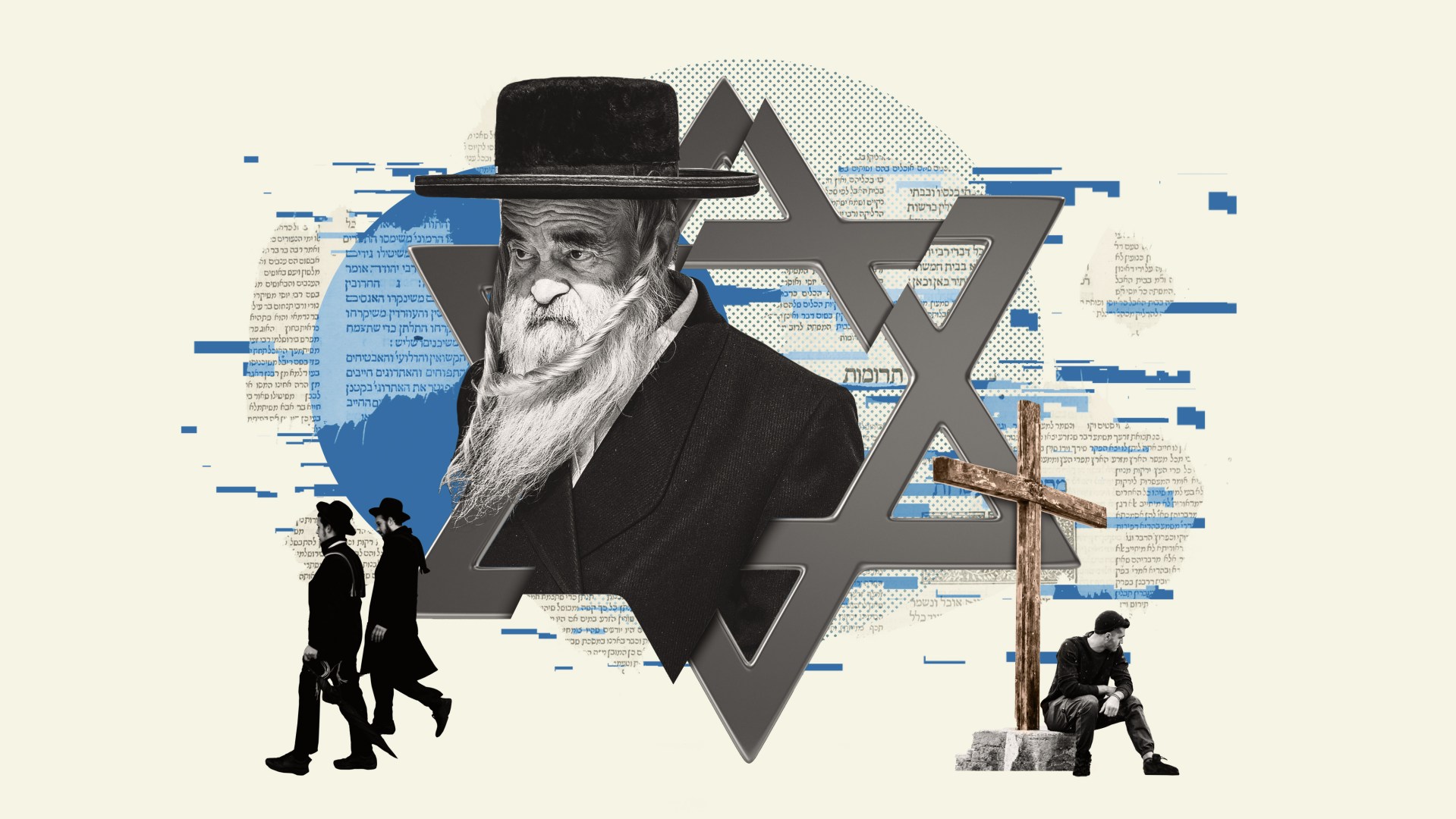

John E. Phelan Jr.’s Separated Siblings: An Evangelical Understanding of Jews and Judaism contains this and hundreds of other surprises. Phelan, a retired theology professor and one-time president of North Park Theological Seminary in Chicago, has provided Christians with one of the most engaging and comprehensive guides to Jewish thought and civilization in the last half-century. Readers are treated to detailed but delightful descriptions of Jewish terms, denominations, understandings of God, religious practices, historical events, and controversies. Phelan also uncovers new findings about the Jewishness of Jesus and Paul, and he relates the history of Zionism to the modern state of Israel.

Surprises in Store

The book is full of enlightening revelations. Christian readers will find resonance in Jewish texts they might otherwise overlook. The Kaddish, for example, is a daily Jewish prayer that begins with words nearly identical to the first petition in the Lord’s Prayer: “May His great Name grow exalted and sanctified.” Phelan observes that while the Talmud—a set of gargantuan reflections on both Jewish oral tradition and the Old Testament—might appear, to outsiders, as obsessed with “minor matters” of religious law, faithful Jews regard it as a divine guide to everyday holiness that puts reason to work “in service of love and obedience.”

Christians sometimes characterize Jewish practice as more focused on externals than matters of the heart. But Phelan points out, among many other examples of heart spirituality, the rabbinic insistence that the annual Day of Atonement “atones only for those who repent.”

Christian critics of Zionism often allege that Jewish yearning to return to Israel only began in the 19th century and was mostly secular. Yet Phelan notes that for the rabbis who edited the Babylonian Talmud in the fifth century, Israel was still the center of the world, and so “any Jew living outside of the land was missing something.” Only in the land could Jews observe the agricultural laws of Torah; therefore, as the Talmud states, “a small group of men in the Land of Israel is dearer to [the Holy One] than the great Sanhedrin outside of the land.”

This book should also surprise readers who have been led to believe that God rejected the Jews as his chosen people when most first-century Jews rejected Jesus as their Messiah. Phelan argues that while God’s covenant with Moses was conditional on Israel’s obedience, his covenant with Abraham was unconditional. Moses warned that God’s people would lose control of the land if they turned to idolatry (Deut. 28:36), but they would remain God’s chosen. As Paul himself states, “God’s gifts and his call are irrevocable” (Rom. 11:29). “Even the rejection of Jesus as messiah does not lead to the final rejection of the Jews,” writes Phelan. Paul “insisted in Romans 11 that the Jews are still ‘loved’ by God” (v. 28).

Phelan takes issue with a common evangelical interpretation of Paul’s teaching of salvation by faith. He argues that Luther’s teaching on justification has often been misunderstood as a form of “cheap grace,” under which works and obedience have nothing to do with saving faith. Yet Paul, as Phelan notes, wrote in Romans 2:13 that “it is not those who hear the law who are righteous in God’s sight, but it is those who obey the law who will be declared righteous.” Phelan says Paul “might have meant two different things” by “law”—law as a way of salvation and law as a guide for life—but “the important point is that Paul, along, by the way, with Jesus, clearly expected that to be a follower of Jesus was to be obedient to the law of God.”

If Paul was more positive toward Jewish law than many have thought, his teaching about the future of Israel was also more Jewish than most have imagined. His prophecy in Romans 11:26 that “all Israel will be saved” has bedeviled interpreters for millennia. But Phelan helpfully shows that this was a common rabbinic teaching that appears in the Mishna, the written record of oral teaching by the rabbis before and at the time of Paul. The Mishna states that “all Israelites will have a share in the world to come,” but it specifically excludes Jews who deny the resurrection of the dead or the inspiration of the Torah, as well as Jews who live licentious lives. Perhaps, then, Paul was adapting a familiar dictum that limited the definition of “Israel” to faithful representatives of all 12 tribes.

In an important chapter that tracks recent Jewish interpretations of Paul, Phelan traces the conclusions of Jewish scholars Daniel Boyarin, Pamela Eisenbaum, and Mark Nanos, who agree that Paul kept practicing Jewish law until his death and taught Jewish disciples of Jesus to do the same. At the same time, Paul taught Gentile disciples not to get circumcised, because Gentiles and Jews were to uphold the law, as Phelan puts it, “in their separate ways.”

If the surprises Phelan documents are intriguing, they are also painful. He highlights many moments in the last two millennia when Christian leaders taught hatred for and persecution of Jews. Erasmus, for instance, refused a trip to Spain because it was too “full of Jews.” Luther preached that if Jews would not convert, “We [Christians] should neither tolerate nor endure them among us.” As Phelan explains, even Karl Barth, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and Martin Niemoller, who “spoke out against the Nazis and anti-Semitism” before and during World War II, nevertheless in their “records reveal anti-Jewish stances and equivocal support for Germany’s Jews until it was once again too late.” The Barmen Declaration (1934) famously declared that Jesus Christ was Germany’s only leader (Führer), but it said nothing about the persecution of Jews because “the Confessing Church would not have accepted it.”

The problem, writes Phelan, was not that Christians were “merely indifferent and uninformed.” Tragically, “throughout Europe, baptized Christians aided and abetted or enthusiastically joined in the slaughter.”

A Few Gaps

Despite the many virtues of this book, there are a few gaps. While Phelan records Rabbi Jacob Neusner’s complaint that Jesus did not address Israel as a whole, he fails to mention that Jesus did just that four times—when he said that in the new world his apostles would judge all 12 tribes of Israel (Matt. 19:28); when he predicted that one day all Jerusalem would welcome him (Luke 13:34–35); when, just before his ascension, he declared that the Father has fixed the time he will “restore the kingdom to Israel” (Acts 1:6–7); and when, by his Spirit, he inspired John to write of the day he would come on the clouds and “all the [Jewish] tribes of the land [of Israel] will wail because of him” (Rev. 1:7, LSV).

While Phelan makes clear the centrality of the Promised Land to Old Testament mentions of God’s covenant with his Jewish people, he neglects similar emphases in the New Testament. For example, besides references to the land as the center of God’s future work (Acts 1:6; Luke 13:34–35), Jesus predicted that one day Jerusalem would no longer be controlled by Gentiles but (implicitly) by God’s Jewish people (Luke 21:24). Paul also taught that God “gave [the Jewish patriarchs] their land as an inheritance” (Acts 13:19, ESV).

In his history of modern Israel, Phelan leaves out the following significant facts: Theodore Herzl, the father of modern “secular” Zionism, hoped for a government that would be Jewish “in character” to protect Jewish culture and religion; when Jordan annexed the West Bank in 1950, both the United Nations and the Arab League condemned this as an illegal violation of international law; and while it is tragic that 700,000 Arabs lost or abandoned their homes because of the Arab-Israeli War of 1948, the war also drove 800,000 Jews out of their homes in Arab lands.

Phelan closes this excellent book with a warning against four “dangerous” readings of the New Testament he calls “anti-Jewish.” First, that Jews are under a curse and even Satanic, a teaching he discerns in the MacArthur Study Bible. Second, that all Jews are responsible for killing Jesus, which he likens to the claim that “Americans killed Lincoln and Kennedy.” Third, that God is done with the Jews, which Phelan says Paul denies when he asserts, “God did not reject his people” (Rom. 11:2). And fourth, that the Pharisees, like all Jews, were invariably hypocrites and legalists—Phelan cites several occasions when they defended Paul, as they did before the Sanhedrin: “We find nothing wrong with this man” (Acts 23:9).

In a day and age when US law enforcement reports more hate crimes against Jews than any other religious group, and when scholars increasingly find that Jesus and the early church were more Jewish than previously thought, Separated Siblings promises to help Christians better understand the Jewish roots of their faith—and why that understanding is so important.

Gerald McDermott recently retired from the Anglican Chair of Divinity at Beeson Divinity School. He is the author of Israel Matters: Why Christians Must Think Differently about the People and the Land and the editor of Race and Covenant: Recovering the Religious Roots for American Reconciliation.