Are evangelical theology and practice of biblical interpretation captive to overly Eurocentric traditions? Increasing numbers of female and nonwhite biblical interpreters continue to reject what they see as patriarchal and sexist understandings of Scripture that reinforce historically white cultural assumptions.

“Objective” biblical interpretation?

In my essay on hermeneutics and exegesis, I point to the development of approaches to Scripture that complement and sometimes contradict historical-critical methods that gained prominence through European scholars of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The historical-critical approach emphasizes the study of language, cultural setting, and literary form. Scholars trained with such an approach sometimes conclude that there is only one way to understand a passage and that their understanding is what the original author intended. Yet the pursuit of a pure, objective, unbiased understanding of biblical authors can itself be a reflection of the interpreter’s own presuppositions.

Greg Carey observes that white male scholars have enjoyed the privilege of their questions, assumptions, and perspectives on a biblical passage being received as the right (and perhaps only) viewpoints. The privilege that accompanies whiteness relates intimately with the traditional norm of biblical scholarship. Carey writes,

‘exegesis.’ … The classic notion of exegesis assumes a fixed, rational, and universal process of interpretation. It also promotes a certain kind of detachment, as if the interpreter were a disembodied mind, free from the constraints of context and daily life.

Everyone brings their biases to the Bible. While we might strive to discern how the first listeners of Scripture understood what they heard, we do well to remember that our reading is influenced by who we are, along with where we’re from and how we experience life.

“Colonized” Biblical Interpretation

In his book, Twelve Lies That Hold America Captive: And the Truth That Sets Us Free, Pastor Jonathan Walton describes a kind of Christianity distorted by colonialism. Walton asserts,

Colonialism created a counter-faith I call White American Folk Religion (WAFR). It’s a set of beliefs and practices grounded in a race, class, gender, and ideological hierarchy that segregates and ranks all people under a light-skinned, thin-lipped, blond-haired Christ.

Issues of “colonized” Christianity run deeper than popular faith practices. As an African American man, seminary professor, and pastor, I’ve experienced firsthand the way colonized Christianity can affect misunderstandings about God, humanity, salvation, and countless other theological convictions. Colonized Christianity has fueled oppression, slavery, racism, sexism and other egregious evils throughout history.

Consider the example of Jesus’ encounter at a well with a Samaritan woman (John 4:1–42). On the one hand are interpreters who see the woman as promiscuous and evasive. She’d had five husbands and was currently “shacking up” (a term many preachers used throughout my lifetime) with a man to whom she wasn’t married. She fetched her water at midday (vv. 6–7) to avoid respectable women who drew water during cooler times. When Jesus acknowledged her many husbands, she changed the subject to the division between Jews and Samaritans over worship (vv. 17–20). During my seminary years, I was taught that the woman was changing the subject because her shameful lifestyle had been exposed. Traditional interpretations, especially since the Protestant Reformation, typically view the woman as more vixen than victim, sexually immoral rather than trapped in circumstances of society.

Female scholars view the encounter in a different light. Frances Gench observes the Samaritan woman as “the first character in John to engage Jesus in serious theological conversation.” Jesus engages the Samaritan woman over an offer of eternal life (v. 14) in the context of the feud between Jews and Samaritans. He follows with the inquiry of her worldly situation, inviting her to recognize him as a prophet and eventually the Messiah (v. 26). The woman enters into serious theological conversation with Jesus over true worship, the Spirit and truth, which then leads to effective witness about Jesus to her people.

As for drawing water at midday, there are countless reasons why a woman may have needed to draw water at noon without assuming anything negative about her character or motives. Mitzi Smith notes that noon “may have been an unusual time of day to draw water … but people do what they have to do and when they have to do it.” Scholars go on to point out the woman’s relatively powerless position in society, particularly with regard to marriage given that marriage was a main source of security for women.

Having learned the traditional view in seminary, I would assume while sharing the gospel that people were hiding their sin, as I was taught the Samaritan woman had been. I expected people to be evasive in conversation with me, so I minimized their theological questions. Over time, however, I became increasingly comfortable questioning what I had been taught about the Samaritan woman, as well as interpretations of other Scripture passages. I began listening better to those I engaged in conversation about Jesus, striving to know them and hear their circumstances rather than assume the worst.

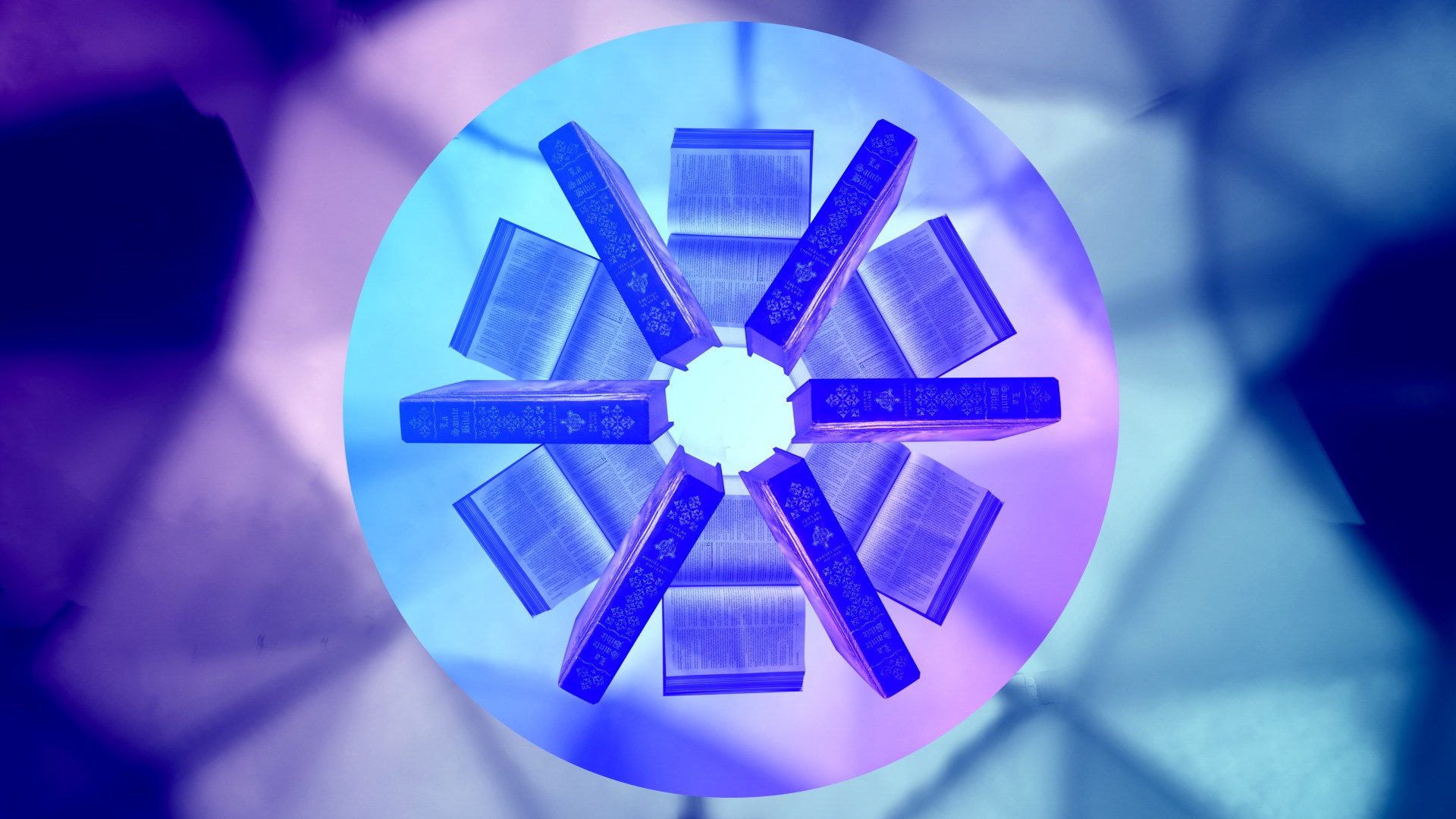

Kaleidoscopic reading

Biblical interpretation happens best in multifaceted community: ancient as well as modern, global, and increasingly diverse. Interpretation should be kaleidoscopic, acknowledging and even celebrating the many colors and cultures that play a part to influence interpretation. Kaleidoscopic interpretation sometimes challenges more conservative and traditional scholarship for the sake of decolonization, but it does so only by mostly using the same hermeneutical tools of study, mining history, language, and culture in search of greater understanding.

Our lenses—our perspectives born from our place in the world—influence our interpretation.

Nevertheless, our lenses—our perspectives born from our place in the world—influence our interpretation. These lenses impact the questions we ask of the text and affect the theological perspectives we glean from Scripture. Increasing numbers of women and nonwhite authors are helping all of us to read the Bible with greater awareness of the world behind the text, which can only broaden and deepen our theological understanding.

Kaleidoscopic reading invites us to be humble, charitable, and patient, as well as inquisitive. We aren’t reading to discern who is “in” and who is “out” or prove who is “right” and who is “wrong.” Instead, we are reading to grow increasingly aware of who God is, who we are, and what it means to be more like Christ. Remember: The point is transformation more than merely information. We must learn to be more collaborative in our study, finding increasing numbers of ways to read and heed the voices of Christians outside the United States as well as from marginalized people within our country.

Kaleidoscopes yield a multicolored view, but they can feel disorienting. Images shift and become complex. Rather than rejecting the disorientation, we do well to embrace it and, as with a kaleidoscope, discover the beauty of light shining though the many reflections of color. Any potential discomfort serves to remind us that we are not the first or only people to read the Bible. Discomfort is part of the journey toward maturity. As we read Scripture as part of a global community of Christ followers, we learn to love God and our neighbors more wholeheartedly.

Dennis R. Edwards is a columnist at Christianity Today.