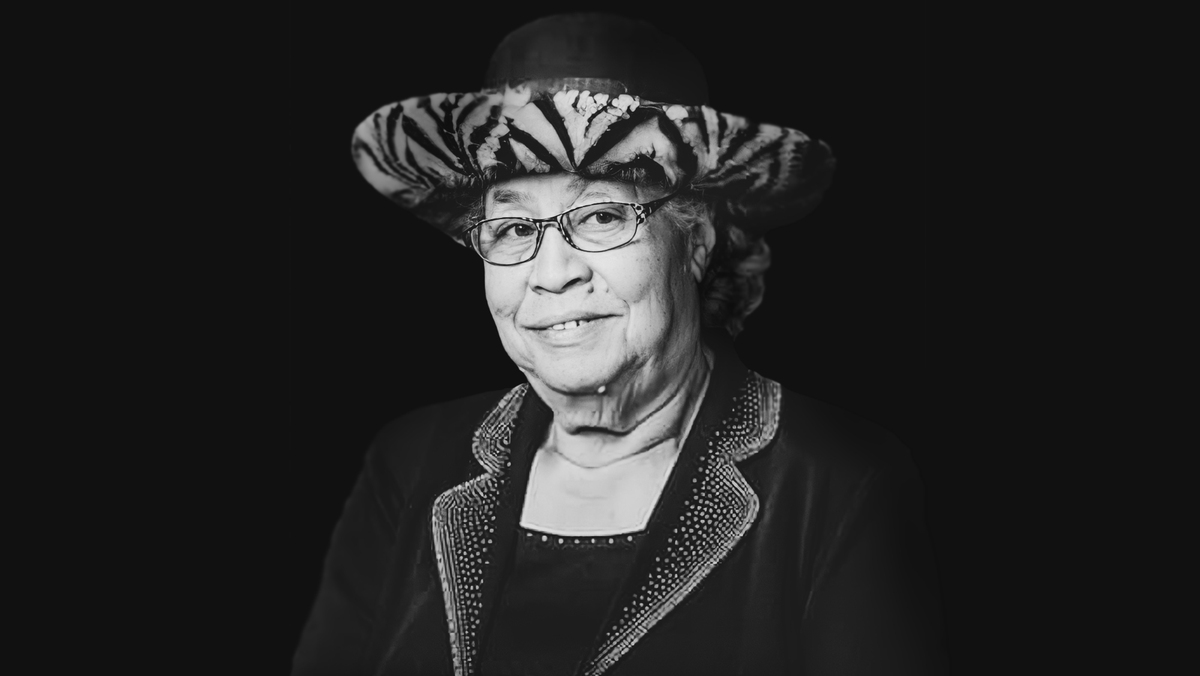

Thelma Battle Buckner learned to play piano in dreams.

She took one lesson as a child, but then the teacher left, and she prayed for help. She received visions in her sleep of her practicing—lessons from God, as she understood it—and quickly learned “Jesus Loves Me,” “How Great Thou Art,” and “Just a Closer Walk With Thee.”

Later, when she played for her father’s Pentecostal revivals, and later, when she and her children performed for Minnesota Lutherans and on the public radio show A Prairie Home Companion, and still later, when she pastored a Church of God in Christ congregation in St. Paul even though the denomination does not believe that women should lead churches and neither did she, she would apologize for her limited skill.

But then she would say, “Don’t blame me if I can’t play any better. God taught me.”

Buckner always recognized her own limitations and God’s call on her life to rise above them. She responded to God with worship, thanksgiving, and work—and urged those around her to do the same.

“I will always serve the Lord,” she sang in one of the gospel songs she wrote herself. “And let me tell you why / He has given me strength in trouble / My guiding light in the sky.”

Buckner died on June 11 at age 89.

The Gospel Temple Church of God in Christ in St. Paul will celebrate her life with music on Wednesday. She will lie in state in the church on Thursday. And she will receive a homegoing service on Friday.

From a long line of fervent Pentecostals

Buckner was born to Nathan and Bessie Wainwright Battle in Racetrack, Mississippi, on April 26, 1932. Her parents were sharecroppers and partners in Pentecostal ministry, regularly leading revivals around the state.

During the summer, Nathan Battle often preached every night. A revival would last a few weeks, Buckner later recalled, but “if the Holy Spirit broke out, it could go on for an entire month.”

The Battles came from a line of revivalists and fervent Black Pentecostals and passed down family stories about the power of God. According to one, Buckner’s grandfather was being cheated out of cotton profits by a white landowner—a common problem for Black families struggling to survive as farmers after the abolition of slavery—and he decided to leave and find a new place to sharecrop. The white owner stopped him with a shotgun.

Buckner’s grandfather started praying in tongues, and it scared the white man, who used a racial epithet and swore Black people “don’t speak other languages.” The man then begged them to leave his land, just as Pharaoh once asked Moses and the Hebrew children to leave their bondage in Egypt.

The story delighted Buckner, and when she was a child, she loved the sound of people praying in tongues and all the noise of a revival.

“There would be singing, shouting, clapping, and jumping,” she wrote in her memoir in 2013. “Folks gave their lives to Christ from all that preaching, shouting, clapping, and jumping.”

After she learned to play piano, Buckner, who was nicknamed “Sassy,” contributed to the holy noise. She was baptized in a Mississippi river at 10, and she gave her life to church, worship, and revival whenever she wasn’t in school.

A difficult marriage

In 1950, Buckner married a young Pentecostal preacher her family had known before he moved from Mississippi to Ohio. Though she had only met Arthur Buckner twice, they corresponded by mail and she agreed to marry him and move to be with him in Ohio.

She quickly regretted the decision.

“What did I know at 18?” she said. “We married as strangers and didn’t know how to get acquainted.”

In 1952, they moved from Ohio to Minnesota, where Buckner’s older brother had started a small Church of God in Christ, but the marriage did not improve.

Buckner’s husband left her at home during the day while he went to work and at night while he went to preach at various churches around the city. She wanted to accompany him and participate as a partner in his ministry, but he refused.

When Buckner got pregnant, he didn’t want her to leave the house at all. And she got pregnant five times in 11 years—including with three sets of twins. Buckner had eight children by age of 29 when Arthur abandoned her. He went to preach at a revival in Chicago in 1961 and never returned.

Buckner was mostly glad to be left to raise the children on her own. She started working at a local factory and trusted God to provide.

“I’m just taking a moment to testify,” Buckner told the church after her husband left. “Every day the Lord makes a way.”

‘It was hard trials and tribulations’

A short time later, Buckner took in eight of her sister’s children when her sister was too ill to care for them. Then she started taking in children whose parents were struggling with drugs and alcohol. She took care of an estimated 500 kids before the county government licensed her as a foster care provider in 1972.

In 1985, she bought a 100-year-old, nine-bedroom house in St. Paul so she could take in more children. The exact number of children she cared for is unknown, but it is believed to be more than 1,000.

“You see a need, you take care of it,” Buckner said. “I don’t know how successful I was. It was hard trials and tribulations and bumping my head. Only way to raise a child is to be persistent.”

At the same time, she and six of her eight children started performing gospel music. First they played in the Gospel Temple, where they attended, and then around the city and the state. They performed as Thelma Buckner and the Minnesota Gospel Twins, and they were a big hit at Lutheran churches and with Garrison Keillor, creator and host of A Prairie Home Companion. They appeared on the show multiple times.

Called to ministry

At 62, Buckner faced a new challenge when her elder brother died and there was no one available to lead the Gospel Temple. She tried to hire a minister, and then another and then another, but no one was willing to take on the small church. She felt God telling her that she should do it.

“I didn’t believe in women priests,” she said. “I came from the old school. I didn’t think I should even be a pastor.”

Buckner was reminded of Moses, who also thought he was unqualified to lead God’s people and his brother should do the job. She thought of Jesus’ statement that if his followers didn’t praise him, the rocks themselves would cry out. And she made a decision.

“I said, ‘Okay, Lord, I’ll speak whenever you want me to,’” Buckner said. “I refuse to let a rock talk in my place, so I’m going to serve the Lord, hallelujah.”

She led the church for 15 years, retiring in her 70s. Gospel Temple is now pastored by her son Dwight.

She went back to school and earned a doctorate from the Minnesota Graduate School of Theology in 2002, at age 70, and launched a ministry teaching young people to sew. They called her “Granny.”

Bucker is survived by her children Gwen Onumah-Onikoro, Bessie Jean Manga, Jesse Buckner, Dwight Buckner, Patrick Buckner, Patricia Lacy-Aiken, Arthur Buckner, and Aretta-Rie Johnson.